1. Forward

By Right Honourable Helen Clark1

The Tigray crisis

In the fifteen months since the war in the northern Ethiopian region of Tigray erupted in November 2020, it has become the bloodiest conflict in the world. It is also among the least reported. It is thought that some 100,000 people have died, but no-one can be ce nes, and even then, have mostly reported from the Ethiopian side of the war. Rarely have reports come from inside Tigray itself; none have been received on the conflict from Eritrea or Somalia.

Volume 1 of “Tigray War and Regional Implications” provided a rare glimpse into the situation with chapters by regional experts. Its publication was welcomed by scholars across the world, with almost 5,000 making use of the report. Volume 2 builds on that work. It is urgently needed: the situation in Tigray could hardly be more critical.

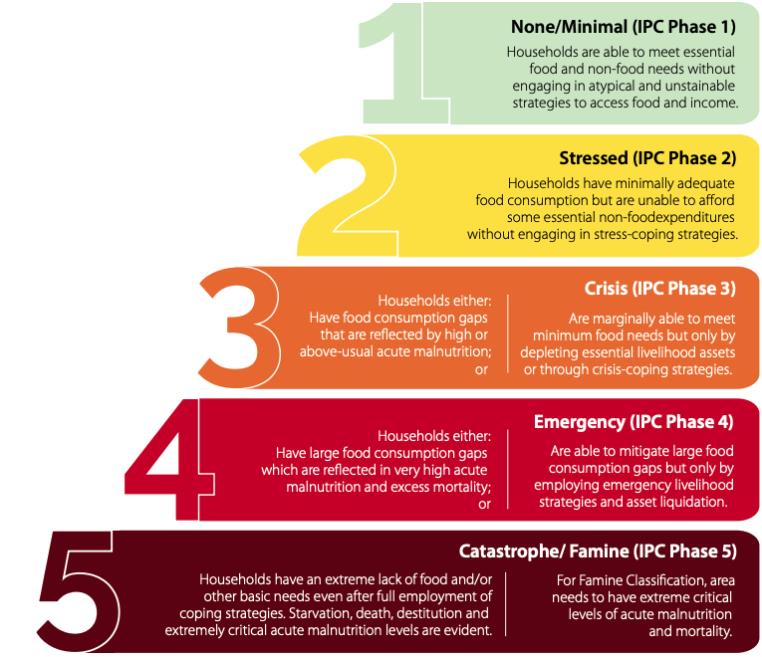

Tigray is now under the equivalent of a medieval siege. It seems that there is a deliberate attempt to starve Tigray’s six million people into submission. The 100,000 Eritrean refugees who were sheltering in Tigray at the start of the war, in camps under the protection of the UNHCR, have been scattered, conscripted, and/or killed. Those who remain survive in the most appalling conditions.2

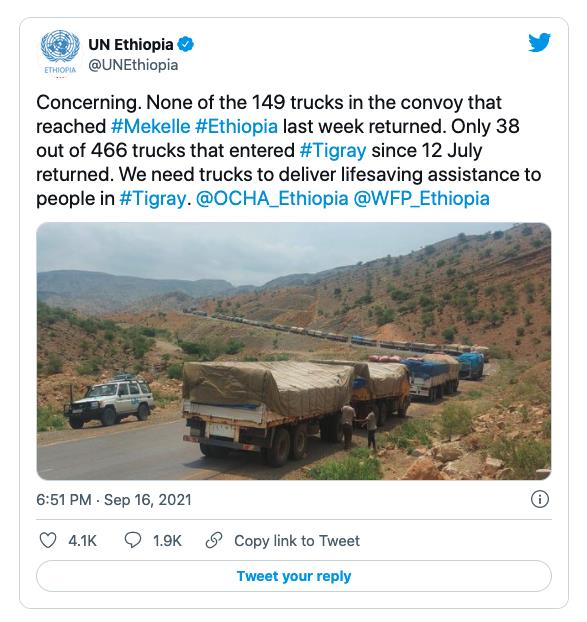

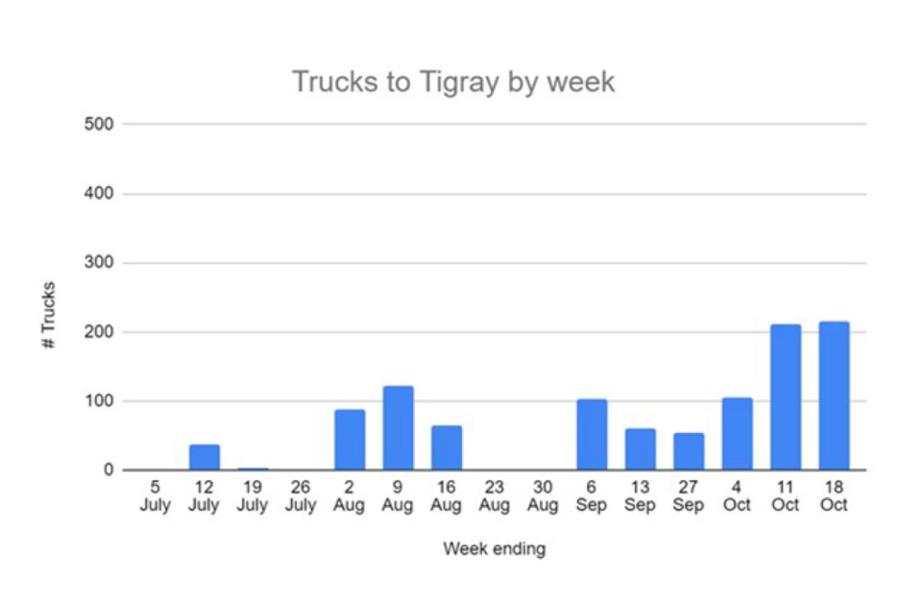

The United Nations and international aid agencies have done their best to reach the neediest. They have – occasionally – been allowed to move vital supplies by truck or planes, but the quantities are so small that they hardly amount to more than a drop in the ocean of need.

As the World Food Programme said in a statement on 24 February 2022: Nearly 40% of people in Ethiopia’s Tigray are suffering “an extreme lack of food.”3 Their assessment found that found 4.6 million people in Tigray — or 83% of the population — were food-insecure, two million of them “severely” so. “Families are exhausting all means to feed themselves, with three quarters of the population using extreme coping strategies to survive,” the WFP said.

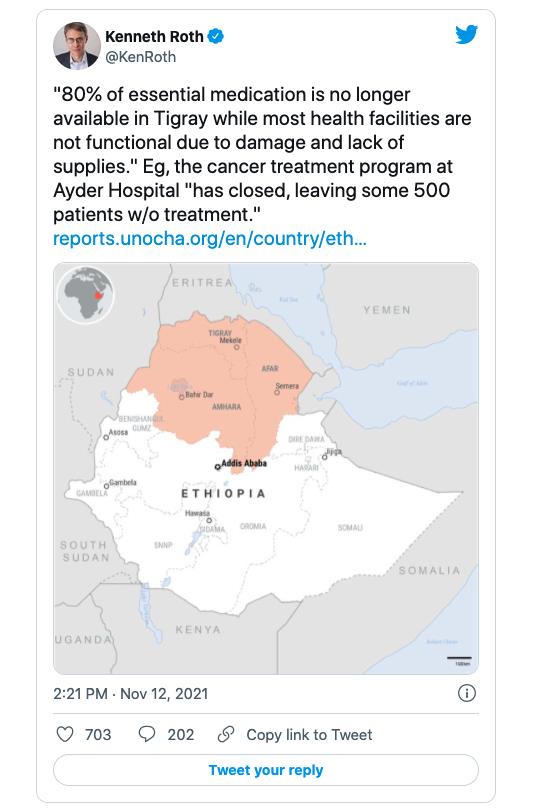

In the largest hospital in Tigray region, a child wounded in an air strike recently bled to death after doctors ran out of gauze and intravenous fluids. A baby died because there were no fluids for dialysis.4 Doctors at the Ayder Referral Hospital in the regional capital Mekelle, told Reuters by phone the lack of supplies is largely the result of a months-long government aid blockade on the northern region. “Signing death certificates has become our primary job,” the hospital said.

With images appearing on social media of the elderly and children close to starvation, no-one can be in any doubt of the seriousness of the situation. Yet still the people of Tigray are undefeated, with their army largely intact. Complex negotiations are now under way involving the African Union and many international actors, including the United States.

Tigray War & Regional Implications (Volume 2)

Volume 1 took the narrative from the start of the war in November 2020 until June 2021. Volume 2 takes it from June 2021 until the end of December 2021.

Written by experts inside Ethiopia and in the outside world, it attempts both to build on the information in Volume 1 and to provide fresh information on topics that have not previously been explored. Volume 2 includes:

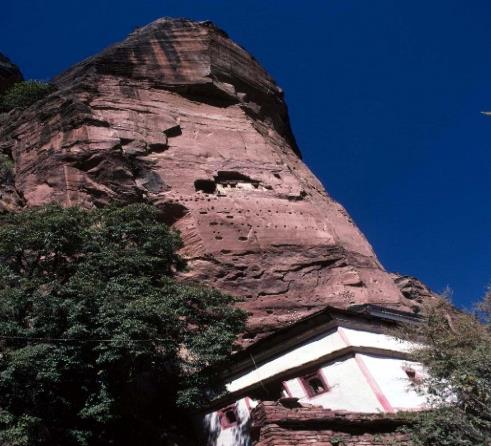

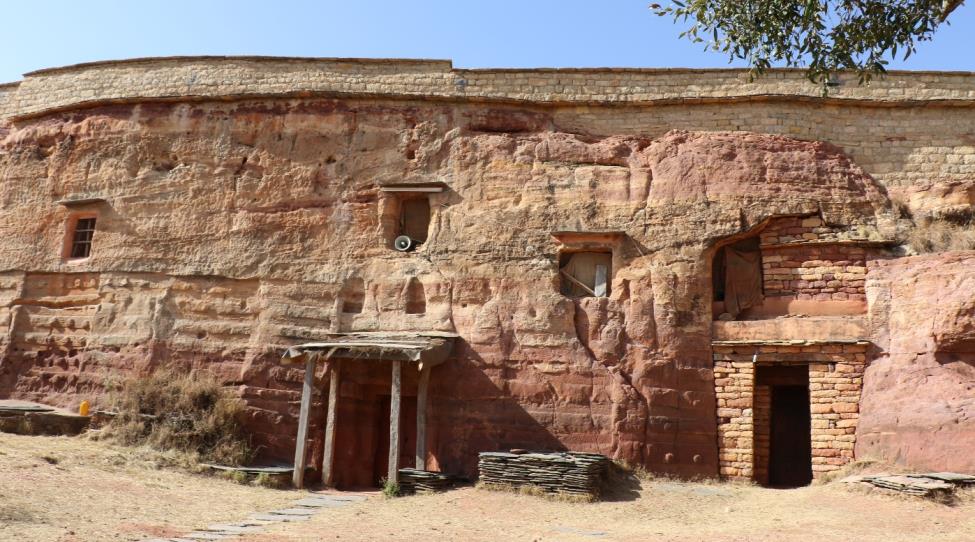

- A first cataloguing of the tragic looting and destruction of Tigray’s unique religious and cultural sites – some of which have global significance;

- The first consideration of the potential role of sanctions against Eritrea to halt President Isaias Afwerki’s continued attempts to exercise dominance in the Horn of Africa;

- An authoritative explanation of how the war unfolded and the deepening food insecurity situation in the months to the end of 2021

- The questions of sexual violence and international diplomacy that were chronicled in Volume 1 have been updated and looked at afresh.

There is an urgent need for this information to spur the international community to action.

While the Biden administration has led international efforts to resolve the crisis, others have been poorly engaged, or have gone out of their way to exacerbate the situation. The role of Turkey and China in providing drones to the Ethiopian military via the UAE is reprehensible. Their drones have not only hit military targets; they have also killed dozens of civilians.5 Russia and China have consistently kept the question of Tigray off the agenda of the UN Security Council, while the African Union has been ineffective in settling a conflict on its doorstep. The European Union has allowed the United States to take the lead, while Britain – stripped of European influence – has been reduced to a bit-player.

The lessons learned from the atrocities in the Balkans or Rwanda appear to have been largely forgotten. The ‘Responsibility to Protect,’ which allowed for an international intervention in critical situations even if the action overrode questions of sovereignty, is seldom discussed.6 If the Tigray war – largely invisible and therefore off the world’s radar – is to be ended, this trend needs to be reversed. Engagement, not indifference, need to be the watchword of capitals from Beijing to Washington.

2. Preface

By Habte Hagos and Martin Plaut7

This report builds on the work that was done for The Tigray War and Regional Implications (Volume 1) that was published by Eritrea Focus and Oslo Analytica in June 2021. Both reports are driven by a single motivation: a concern for the tragic consequences for the people of Ethiopia and Eritrea in particular, and the Horn of Africa at large, of the war that erupted in November 2020. The conflict pitted the Tigrayans people against troops from Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Somalia with the support of the UAE, Turkey, Iran, and China, amongst others. The warring factions have paid a very heavy price; so too have the civilians caught up in this brutal war.

None of the tragic suffering has been as under-reported as the death and casualties inflicted on the people of Eritrea. Already trapped in Africa’s worst dictatorship, without recourse to independent courts, judiciary or a functioning constitution, Eritreans have also had to endure pain that is little recognised by the outside world. The dictatorship of President Isaias Afwerki has meant that the media – local and international – are either suppressed or so tightly controlled that only the government’s version of events emerges. Faint whispers emerge from inside Eritrea; families have heard from their loved ones; brave individuals smuggle truths out of the country, but overall, the country suffers in silence.

What we know is that Eritreans in their tens of thousands have been sent to the front lines as “National Service” conscripts. They have only two options: fight or flee. Some have fought in Tigray and have been responsible for appalling atrocities that have certainly been tolerated by, and probably been encouraged by, their officers. Some have fled to Sudan or deserted from the Eritrean army while inside Tigray or Ethiopia. Many have paid with their lives; still more have returned to Eritrea to live with their disabilities as best they can. This report contains information about the financial underpinnings of the Eritrean regime, much of which has never been brought together before. We are determined to continue collecting information about the intolerable persecution Eritreans face and making it public.

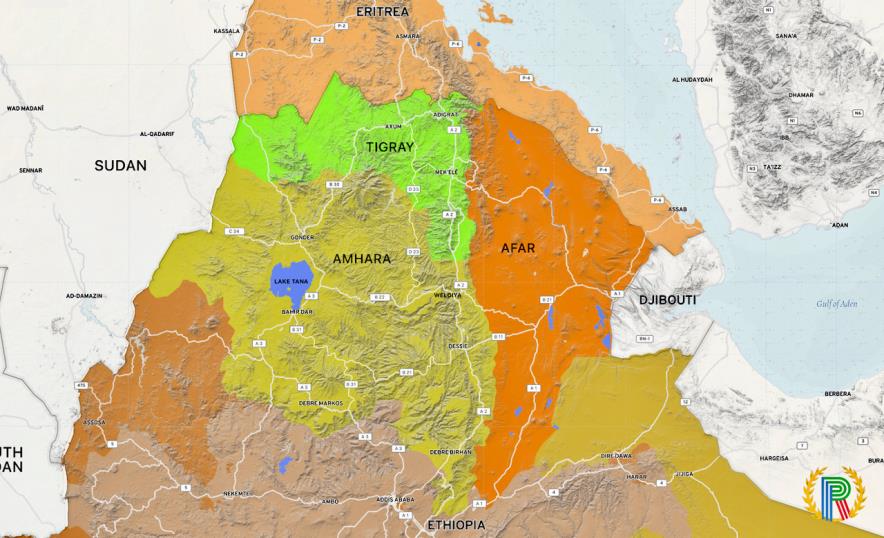

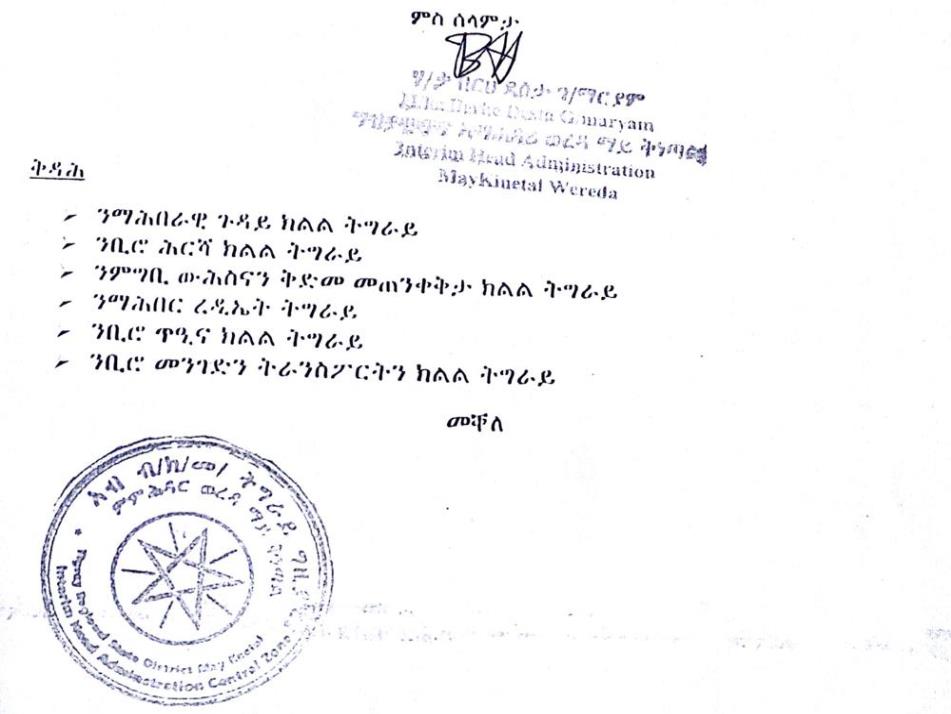

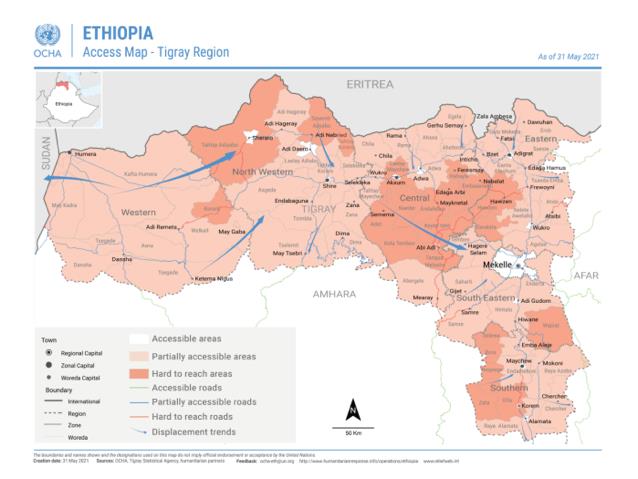

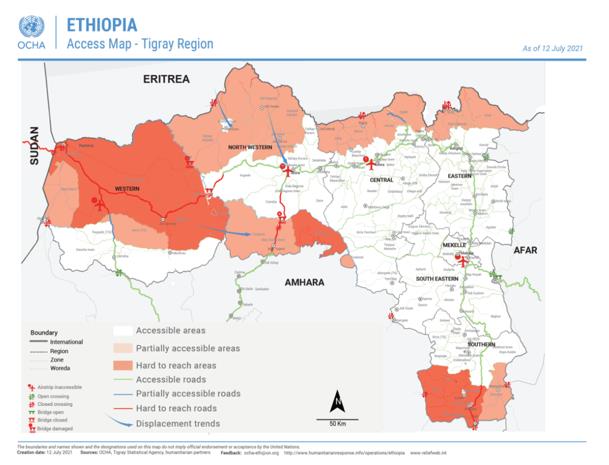

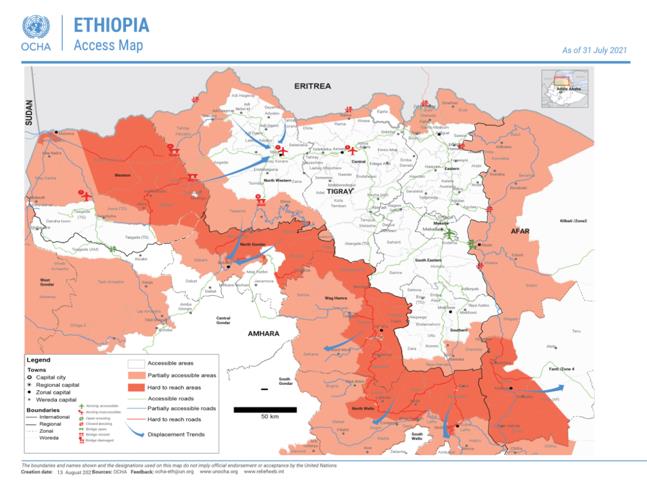

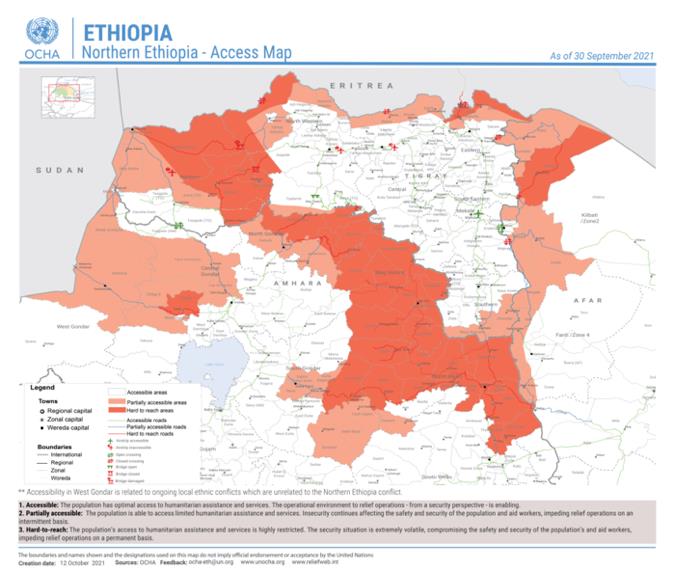

Having said this, the majority of this report focusses on the war and its consequences for the people of Tigray and their neighbours. We are enormously grateful to everyone who has contributed, but are particularly grateful to the Right Honourable Helen Clark, former Prime Minster of New Zealand, for her unstinting support and encouragement. Some of the authors must unfortunately remain anonymous, or rely on nom de plumes, but we are happy to acknowledge the contributions of Prof. Araya Debessay, Prof. Desta Asyehgn, G. E. Gorfu, Dr. Hagos Abrha Abay, Sally Keeble, and Felicity Mulford. We are very grateful for the work of Reclaim Eritrea8 in providing the maps which are a graphic guide to the development of the war in Ermias Teka’s chapter on the Progress of the War. Prof. Kjetil Tronvoll, who is our co-publisher, had played a vital role in backing the report and contributing an important and insightful introduction.

As the report is published there has been a lull in the fighting. There are reports of intensive negotiations to end the war: we hope they are productive and end the suffering, allowing the political and physical reconstruction to begin. If this opportunity is not seized there is every indication that the conflict will become entrenched and could last for years. This tragedy must be avoided at all costs.

The views expressed in this report is that of the authors, and do not necessarily represent the views of Eritrea Focus or Oslo Analytica.

3. Introduction: An end to the Ethiopian civil war?

By Professor Kjetil Tronvoll9

The Ethiopian civil war, which unleashed devastation and horrors since it began in November 2019, continues unabated in 2022. The frontlines have continuously shifted, displacing millions of civilians and ruining infrastructure across Tigray, northern Amhara, and Afar regional states. Attempts to facilitate a secession of hostilities and peace negotiations by international envoys have all failed, as the political objectives of the various belligerent parties appears irreconcilable.

The Ethiopian war theatre was the largest armed conflict in the world in 2021. Tens of thousands of combatants have perished on the battlefields, thousands of civilians have been massacred, and rape and famine have been weaponised. A confounding element in the Ethiopian war is the involvement of a host of belligerent parties, the key being the Tigray Defence Force (TDF) and the Oromo Liberation Army (OLA) as allies on one side, fighting against Ethiopian federal and regional government troops and militias, irregular Amhara militias (Fano), and – not least – the Eritrean Defence Forces (EDF). Furthermore, minor resistance movements and localised militia or vigilante groups have allied themselves with one or other of the key belligerents, further complicating the analysis of the war, the attribution of war crimes and atrocities committed, as well as the pursuit of an overall peace process.

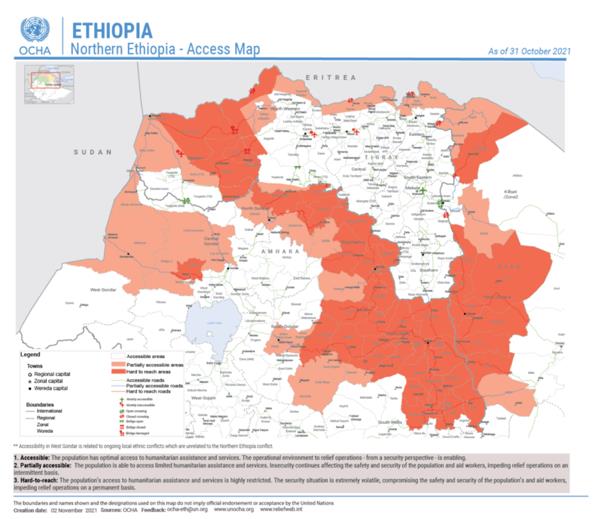

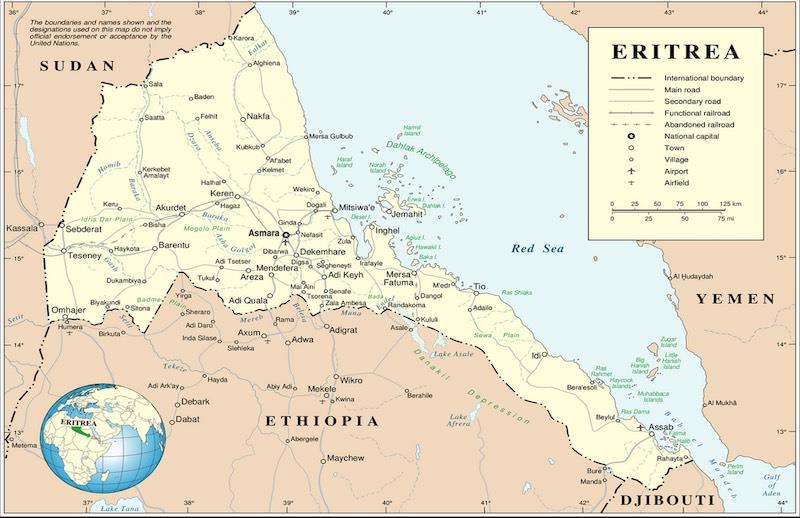

This report is a sequel to last year’s study (Volume 1) which inter alia detailed the outbreak of the conflict, its humanitarian impact, and diplomatic efforts to end the hostilities. Through this volume we continue our efforts to document and expose the devastating ramifications of the war. A detailed overview of the evolvement of the war, including illustrative maps, is presented by Ermias Teka. The dire humanitarian impact, with millions in need of aid and hundreds of thousands starving, is analysed by Felicity Mulford. Sally Keeble focuses on the horrendous sexual assaults inflicted upon girls and women by the warring factions as part of their war strategy. The war in Tigray also involves eradicating the region’s cultural and religious heritage. The looting and destruction of religious and cultural artefacts have been widespread, an issue investigated by Hagos Abrha Abay. The US sanctions on Eritrea for its atrocity warfare on Tigray is discussed by Habte Hagos. The internationalisation of the Ethiopian civil war is also notable with the involvement of the Eritrean and Tigrayan diaspora in either furthering the conflict abroad, or trying to assist their communities back home, an issue analysed by a group of prominent scholars. Ethiopia’s diplomatic contacts and influence across the region are discussed by an expert in the subject matter who wishes to remain anonymous.

Finally, since the outbreak of the war, various diplomatic initiatives have been launched and special envoys tasked to try to bring the belligerent parties to the negotiation table, a process examined by Martin Plaut.

Volumes 1 and 2 of the Tigray War and Regional Implications provide the most comprehensive and up to date analysis on the tragic civil war currently unfolding in Ethiopia.

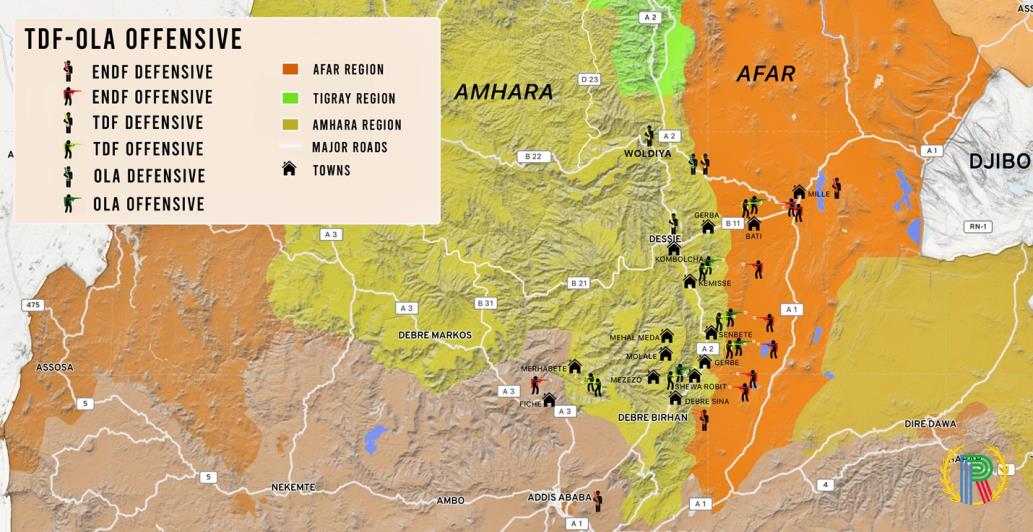

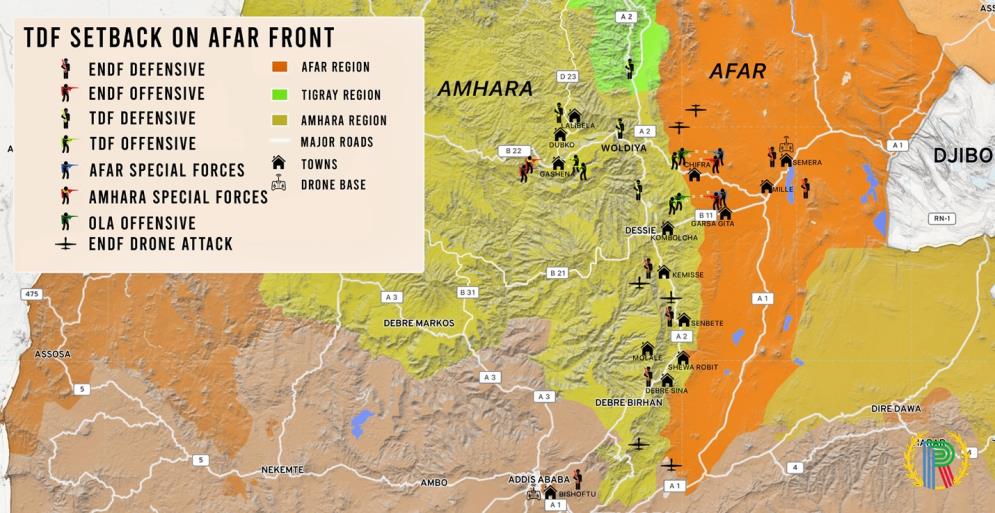

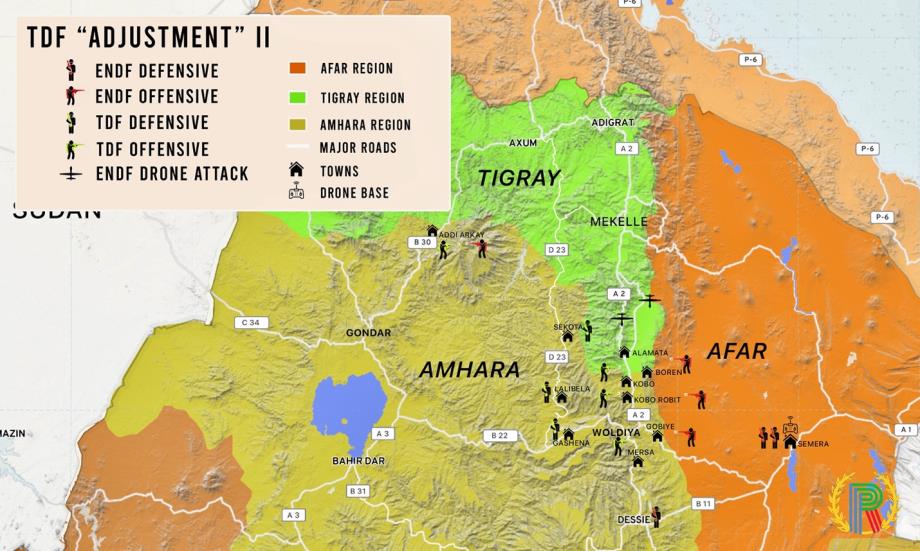

The ebb and flow of war

After reclaiming control of Mekelle and central Tigray in June 2021, the TDF’s steady march towards Addis Ababa surprised many observers. When the strategic towns of Dessie and Kombolcha fell under TDF control at the end of October, it created widespread concern of a potential collapse of the Federal Government. Prime Minster Abiy Ahmed declared a nationwide State of Emergency. A month later, at the end of November, the combined TDF/OLA forces reached Debre Sina, a town only 220 km north of Addis Ababa. The diplomatic community scrambled to evacuate their citizens and Addis Ababa’s authorities asked alarmed inhabitants to be prepared to defend the city at any cost. In response to the imminent threat, PM Abiy declared a ‘total war’ against the rebels and vowed to go to the frontlines to lead the fight himself. Thenceforth, however, a set of factors contributed to a shift in the tide of war in favour of Ethiopia government and its allies.

In early December, TDF started what they called a tactical retreat of its forces from the southern frontline, easing the pressure on the capital Addis Ababa. By calling it a ‘tactical’ retreat, it signalled that the strategic objective of their struggle remained unchanged, but the military tactics to achieve them had to be revised. Subsequently, the TDF announced that all its forces were withdrawing from the Amhara and Afar regional states to return to Tigray.

It appears that there were three key reasons for the TDF tactical withdrawal, rooted in military, political, and diplomatic concerns. First and foremost, it seems clear that the military balance on the battlefield tilted in the Ethiopian government’s favour. A key factor for this change was the massive arms purchases undertaken by the government during 2021; acquiring among other equipment combat drones. The long TDF supply route from Tigray to the southern front was particularly vulnerable for drone attacks and destroyed lorries supplying fighting units. Furthermore, the extended TDF lines offensive made their flanks vulnerable from attacks from the east by Afar units and from the west by Amhara forces. At the same time, it is important not to underestimate the effect of PM Abiy’s call for a total war and his encouragement of civilians to join him on the frontline. This created a surge of national fervour among his supporters, who willingly offered to sacrifice themselves in combat. Although Tigrayan officials claimed that they had their fighting army remains intact, as they pulled back without engaging in battle, it seems plausible that a sustained high attrition rate would be difficult to sustain, given the comparatively smaller TDF recruitment base.

As alluded to by Tigrayan officials, however, there were diplomatic and political concerns as well, which compelled them to withdraw, which are key to a possible negotiated solution to the war. Politically, a coherent and consolidated agreement on a possible transitional government with their ally OLA and representatives from the ‘federalist alliance’ seemed to be wanting. The TPLF has been clear that they have no interest or ambition in regaining central rule over Ethiopia. The responsibility to lead a possible transitional government, achieved militarily or politically, would thus rest on a broader Oromo led political opposition. This has yet to be consulted, because of the political context in the country. No doubt there is deep political distrust of the TPLF among many of the pro-federalist political opposition fronts in Ethiopia; mistrust based on their experiences of the draconian rule of EPRDF over 27 years. To craft a new joint political platform among former adversaries in haste during a war turned out to be difficult. A stable Tigrayan-Oromo political relationship would have to be carefully mended, and then extended to other movements, before a creditable alternative to the Prosperity Party rule could emerge.

In the end it was the diplomatic pressure brought to bear on the TPLF that was the most important factor in halting the final offensive on Addis Ababa. The US administration has been critical in this regard, with its special envoy ambassador Jeffrey Feltman, giving an unequivocal messaging to TPLF. He declared in November: “We oppose any TPLF move to Addis or any TPLF move to

besiege Addis.” The TPLF leadership are, perhaps a little paradoxically, astute internationalists who put considerable efforts into maintaining and balancing international relations. They therefore seemed hesitant to continue an advance on Addis in the face of broad international opposition. Speculation is rife about the possibility of a confidential agreement between US and Tigray government on a peace deal with the Ethiopian government. However, none of the parties have confirmed this.

‘National dialogue’ without peace?

The TDF withdrawal created an opportunity for political dialogue between Mekelle and Addis Ababa. This could have led to a cessation of hostilities, paving the way for peace negotiations to find a durable solution to Ethiopia’s intrinsic political challenges. President Debretsion Gebremichael of Tigray has explicitly stated that only an all-inclusive negotiation process can solve the mounting challenges facing Ethiopia.

In a letter to UN Secretary-General Guterres on 19 December 2021, the Tigray regional president Debretsion Gebremichael made a notable proposal, without any preconditions, for “an immediate cessation of hostilities followed by negotiations.” In the letter, however, the TDF leader lists a set of issues that should be addressed by the UN Security Council and resolved as integral part to a peace process. Among these are restoring the full legal authority of the Tigrayan government over all its territories and lifting of the siege. The Ethiopian government did not officially respond to the call, but instead, according to TDF spokesperson Getachew Reda, continued its military operations against Tigrayan, including reportedly bombing Mekelle. This Is apparently to deflect international attention from a call for a cessation of hostilities and peace negotiations. In spite of this, the Ethiopian government has fast-tracked its attempt to establish a so-called “National Dialogue Commission” that is tasked to reconcile the deeply politically divided country. The objective of the Commission is supposedly to create an inclusive and participatory process to reach a consensus on how to tackle the challenges facing the nation. However, when presenting the proclamation establishing the Commission, the speaker of the House of Representatives Tagesse Chafo, firmly rooted its work and vision in the Prosperity Party’s ideology and programme. He framed it as a political tool to gather support for the incumbent’s agenda, and not as a vehicle to establish an all-inclusive dialogue process fostering a common understanding among the manyfold political opinions and groupings in the country to be enshrined in a new social contract with the citizenry. Tagesse concluded stating that the “terrorists” i.e., TPLF and OLA cannot participate in the national dialogue and will be dealt with according to the law that relates to them. A similar sentiment was later echoed by Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, calling the TPLF and OLA “devil forces.” In this vein, state minister Redwan Hussein, has claimed that there are actors other than the TPLF who represent the Tigrayan people. He said that one might expect government friendly Tigrayan parties, such as the Tigray Democratic Party and the Tigray People’s Party might represent Tigrayan interest in the national dialogue process.

In early January 2022, the Government dropped charges against, and released some key opposition leaders, who had been in detention for a year and a half, with the stated intention that their participation was needed in the national dialogue. On the day of his release, Eskinder Nega from Baldaras for Democracy party praised the ENDF and the Fano militia’s war against Tigray. Bekele Gerba and Jawar Mohammed from Oromo Federalist Congress, on the other hand, contemplated the situation. After several days they issued a statement calling for an all-inclusive dialogue process and declined to participate if the OLA and TPLF were not included. At the same time, TPLF leaders captured during the war were also released from prison, most notably Sebhat Nega, the “father” of the Front, and Abay Woldu, the former party chair and regional president. They were released on ‘humanistic ground’ due to their old age and ill health. Their participation in a national dialogue were not wanted, and the government’s “terrorist stigma” on TPLF remains in place.

If not peace negotiations now, then what?

It seems clear that western pressure on Ethiopia to accept negotiations has failed, as Ethiopia has obdurately rejected what they term neo-imperialists interference into their sovereign affairs and has accused the US and EU of being supporters of the TPLF’s agenda. An additional element of concern is the obvious fact that Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed does not exercise authority over all his allies in the war against Tigray. It seems equally doubtful that President Isaias Afwerki of Eritrea or the Amhara leadership will accept a peace process which, for instance, entails Eritrean political concessions or the return of west Tigray under the control of Mekelle. So even if Abiy Ahmed and some individuals in the Prosperity Party leadership might, hypothetically, be interested in settling the dispute with the Tigrayan leadership, the Prime Minister may be prevented from doing so by his brothers in arms.

For the time being, it seems that the Ethiopian leadership and their allies have abandoned the prospect of defeating the TDF. Abiy Ahmed admitted that the war on Tigray had turned its people against the central government. Instead, Ethiopia and its allies have settled on conducting a siege warfare against Tigray by halting their advances and blocking all access to the region. At the same time, they have continued their aerial bombardment of cities and important sites across the region. The objective of the siege is to grind the Tigrayan people and leadership into submission. The Prime Minister hopes that the people will eventually revolt against the TPLF leadership. A similar strategy was previously attempted by Mengistu Hailemariam and the Derg military junta in the war against the Tigrayan insurgency in the 1980s, without success. There is no sign that it will be any more successful today.

Facing siege warfare, the TDF cannot afford to remain idle for long. Their only option, apart from surrender, will therefore be to re-engage militarily to try to shift the balance of power on the battlefields once again. President Debretsion informed this author in a satellite conversation in late December that the window of opportunity is brief: “We have a huge army intact and cannot sit idle to watch our population starve to death.” The Ethiopian government did not respond to Tigray’s call for a cessation of hostilities and the siege of the region remains in force.

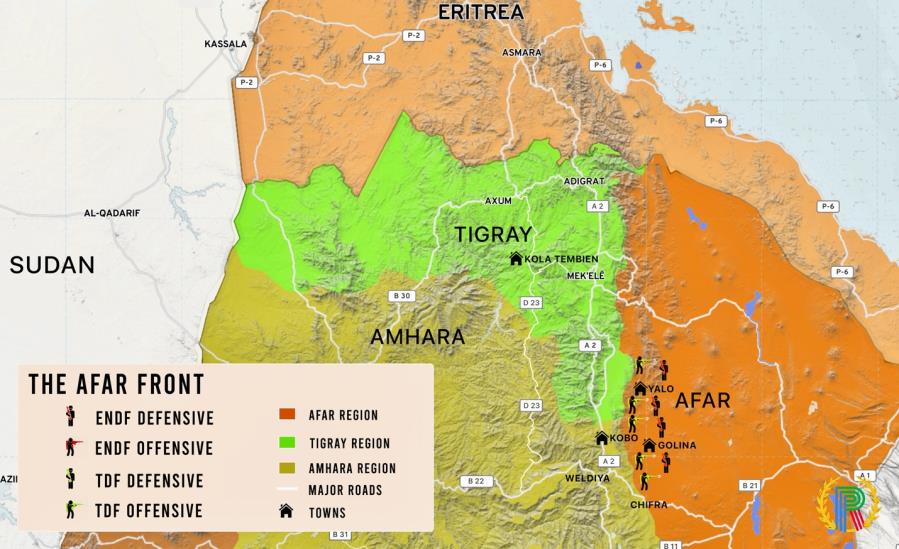

The TDF started a new offensive in Afar region in late January 2022. At the time of writing the military and political objectives of this offensive are unknown. Speculation is rife that the TDF may launch a new offensive to recapture (parts) of west Tigray, to create a corridor to the Sudanese border. Retaking west Tigray, constitutionally defined as part of the territory of the Tigray regional state, would not breach with the international consensus that TDF should remain within the region of Tigray. West Tigray would connect the region to Sudan and provide the Tigrayans access for humanitarian supplies. The Sudan cross-border circumvent the siege imposed by the Ethiopian government. At the same time, necessary military supplies might also reach Tigray from potential allies in the region that would enable the TDF to strengthen their defence and anti-drone capacities, rendering the siege war outmoded. If such a shift of military strategy is successful, it might compel the Ethiopian government to acknowledge the Tigray government as a counterpart in a genuine peace negotiation process.

After war – Ethiopia reconfigured?

There are few signs today that a comprehensive peace process between the TDF/OLA and the government alliance will take place in the near future. Hence, the likelihood of a sustained civil war is high. However, if all-inclusive peace negotiation were to take place, it is hard to envisage that ‘Ethiopia’ as we knew it before the outbreak of the war would be re-established. The war has partly been fought over competing visions of what Ethiopia is, and how it should be organised, mainly along a continuum of centralised vs a devolved model of statehood. Finding a durable solution to this question is a daunting task that peace negotiators will need to tackle. The fundamental issue is how the Ethiopian state ought to be reconfigured to create sustainable peace between the “nations, nationalities, and peoples” of the territory. Is it at all possible to achieve a compromise which will allow a “living-together” model, after what many perceive to be a genocidal war? Many observers doubt this and are warning of a Balkanisation of Ethiopia, at par with former Yugoslavia.

The 1991 “Transitional Charter”, which provided the framework for the 1995 Ethiopian Constitution, was supposed to serve as a forward-looking peace agreement. The two main architects of the Charter, the TPLF (led by the late PM Meles Zenawi, PM at that time) and the OLF (led by Leenco Lata), designed a multinational (ethnic) federal state model with the objective of creating permanent trust between the central government and the “nation, nationalities, and peoples” of the land. They did so – at least on paper – by reversing the direction of authority and the repository of sovereignty. “All sovereign power resides in the Nations, Nationalities and Peoples of Ethiopia” states the Ethiopian Constitution (Art. 8.1); as such the country is defined as a ‘coming-together’ federation. Furthermore, by including an ‘exit-clause’ (Art. 39.1) allowing any group to leave the federation, it was assumed that there would be no reason to harbour distrust towards a potential power-abusing central government.

The genocidal warfare waged against Tigrayans by the combined forces of Ethiopia, Eritrea, and Amhara, (with Somali support) has possibly created such a deep schism between Tigray and rest of Ethiopia that it will be impossible for the majority of Tigrayans to live in trust and safety among their former adversaries. Concomitantly, the continued Oromo insurgency will also take its toll on the Ethiopian state model.

The Tigray government has stated that the status of Tigray in Ethiopia after the war must be left to the Tigrayan people to decide through a referendum. If the question in the referendum will be yes or no to independence, it seems likely that a majority of Tigrayans will vote ‘yes.’

However, no internationally facilitated peace negotiations could entertain a process which would lead to the break-up of the Ethiopian state. A break-up of Ethiopia, or the secession of Tigray and possible Oromia, could only be achieved, (if it is desired) through a military victory of these forces and the establishment of a transitional government in Ethiopia which would accept such a solution. It would be on a par with the arrangement in 1991 which endorsed the independence of Eritrea.

If secession is out of the question, what model of government can be designed to appease the Tigrayan and Oromo (and others) who are distrustful of a centralised Ethiopian state, while at the same time preserving the territorial integrity of Ethiopia? A possible model maintaining the polity of Ethiopia intact is to transition into a confederate state model (or a so-called ‘loose federation’). A split-sovereignty confederation, where sovereignty rests with the member states of the confederation and the confederate government holds power over a limited number of issues (like fiscal/currency, aviation, etc), will preserve the integrity of “Ethiopia” while concomitantly guaranteeing the political self-governing rights and security interests of the member states.

Reaching a consensus on a new Ethiopian state model would be an uphill task, considering the antagonistic, divided, and confrontational political context existing in the country today. A state model is also a reflection of the identity it represents.

Presently there is no common, all-embracing understanding of what “Ethiopianess” consists of. It is a defining characteristic that is fiercely contested by the many belligerent parties to the conflict.

International actors can only serve as facilitators of a peace process at the behest of the warring parties; a sustainable solution must be found and agreed upon by the Ethiopians themselves. At every other crossroads in Ethiopian political history, the victors have imposed their solutions on the vanquished, whose interests have been neglected and suppressed. As the current discourse suggests, this seems to be the approach being taken by the current powerholders in Addis Ababa. How durable it will be this time around, remains an open question. The outcome of the war is uncertain at the time of writing, but one thing seems clear – Ethiopia is unlikely to ever return to the status quo ante.

4. An overview of the Tigray conflict: June to December 2021

By Ermias Teka

4.1 Introduction

Barely seven months after facing military annihilation at the hands of the Ethio- Eritrean army, Tigrayan forces pulled off one of the most significant military reversals in recent African history.10

The Tigrayans avoided, as much as possible, prolonged fighting. Unless strategically significant, maintaining defensible territories was never their priority. Upon facing a stronger, determined offensive, they retreated quickly to save their strength and countered by choosing the time and place when the opponent was vulnerable. Unlike the EPLF’s military tradition, the ‘Woyane’ as the Tigrayans were known, adopted highly mobile guerrilla strategies which were honed and perfected by TPLF military commanders during the 17 years armed struggle which ended with their capture of Addis in 1991. Even during conventional battles, TDF’s units employed quick and focused attacks preceded or followed by constant shifting of positions using similar principles as in a guerrilla warfare. They rarely deployed larger than battalion sized units at a time but used several of them from multiple sides to launch coordinated attacks. To this end they employed the wealth of experienced medium and high-level military leaders had at their disposal to pull of remarkably well orchestrated manoeuvres between their units.

In a series of battles in central Tigray, the Tigray Defence Forces (TDF), led by the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), succeeded to neutralize some of the best trained and highly-experienced divisions within the Ethiopian National Defence Forces (ENDF). The ENDF subsequently withdrew from the Tigray. Determined to break what the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) labels a ‘de facto aid blockade’ and to regain lost territories, Tigrayan forces then went further and launched operation “Tigray Mothers.” It was their first in a series of conventional battles to retake southern and southwestern Tigray which remained under federal government and Amhara control. A series of brief but intense battles with the ENDF and Amhara forces saw the TDF recapture areas around Mai Tsebri in southwestern and southern Tigray – territories fiercely claimed by the government of the Amhara Region.

Contrary to the expectations of many, the TDF refrained from carrying out major operations to take back western Tigray which would have served as a crucial supply corridor to Sudan. Similarly, territories to the northwest remained firmly under the control of Eritrean forces and the Tigrayans made little or no effort to reclaim them militarily.

This meant that, despite the relatively significant TDF military successes against the formidable Ethio-Eritrean alliance, Tigray remained under siege. The federal government insisted the withdrawal of its forces showed its commitment to peace and rejected accusations that it was intentionally facilitating man-made starvation in Tigray. However, all services; including banks, telecommunications, electricity, and land transportation remained largely blockaded by federal authorities and lifesaving humanitarian aid was largely denied access.

The de-facto siege and humanitarian blockade gave the Tigrayan forces the justification to reject the government-declared unilateral ceasefire and to launch offensives into Amhara and Afar regions “to break the siege.” Accordingly, the Tigrayan leadership mobilised its forces on the region’s southwestern and southern fronts. The short-term goals of the operation were to neutralize the bulk of the ENDF and Amhara forces that were allegedly planning to re-invade Tigray, and to set up a buffer zone to prevent future offensives.

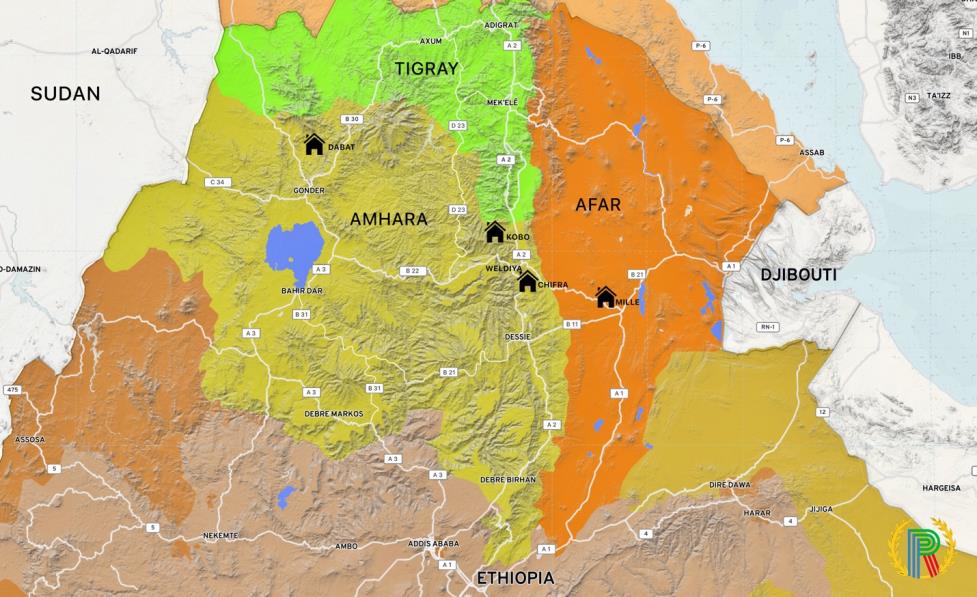

The Tigrayans’ southwestern offensive was probably aimed at capturing the historic town of Gondar, once the capital of the Ethiopian Empire. By achieving this, the TDF hoped to sever the supply route for the bulk of the ENDF entrenched in western Tigray and force its capitulation without resistance. The TDF’s southwestern offensive succeeded in pushing deep into northern Amhara as far as Dabat, 53 kilometres from Gondar. The southern offensive succeeded in capturing the strategic town of Kobo and its surroundings, cutting off the A2, the main north-south highway between Addis Ababa and the Tigrayan capital, Mekelle. This inflicted a major blow to the ENDF.

Meanwhile, another TDF detachment had quickly deployed to the southeast into the Afar region and after a number of brutal battles, took control of Yalo, Golina and Aura woredas and advanced halfway into Chifra. The TDF’s offensive into Afar was ultimately aimed at capturing Mille – a town along the Addis Ababa-Djibouti highway that serves as the main commercial artery for the federal government, linking the capital with the Red Sea. By capturing Mille, the Tigrayan command appeared to have intended to force the central government to open negotiations. However, the TDF’s repeated attempts to capture Mille failed; a serious blow for the Tigrayan forces. They were held up by the combined ENDF and Afari Special Forces (ASF) at Chifra, and later at Garsa Gita, and were forced to abandon the Mille operation entirely.

Similarly, fierce resistance and counterattacks forced the TDF to retreat from the vicinity of Dabat to Zarima.

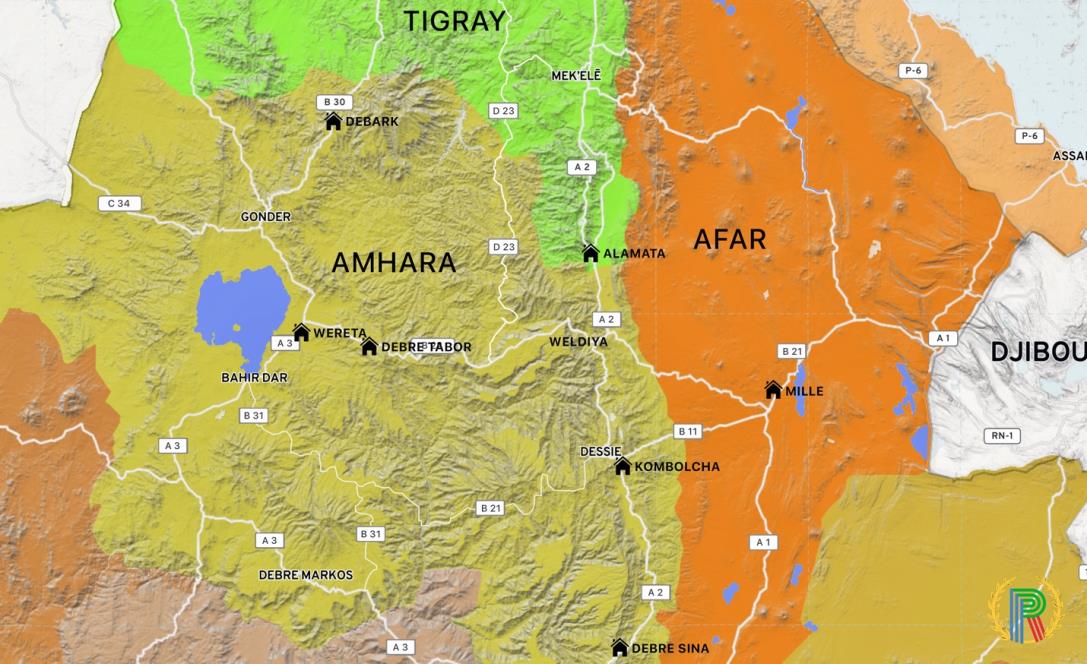

With the TDF advance on both the Gondar and Afar fronts grinding to a halt, Tigrayan forces then resorted to another offensive directly southwards along the B22 highway aimed at capturing Wereta. The objective appeared to have been to facilitate the TDF advance on Gondar by cutting off the supply route from Bahir Dar to Gondar, while simultaneously forcing the redeployment of some of the Ethiopian and Amhara forces from the heavily-manned Debarik frontline, in north of Gondar. The TDF southern offensive along the Weldia-Wereta highway progressed as far as Debre Tabor.

The TDF’s rapid advance left its forces exposed with lengthy supply routes. The Ethiopian forces took advantage of this weakness. A major ENDF-ASF counteroffensive was launched at Gashina, aimed at cutting off the bulk of Tigrayan forces that had been concentrated around Debre Tabor. It forced a rapid TDF withdrawal, and they eventually abandoned their objective to capture Wereta, which would have cut off the road to Gondar. The mass mobilisation and deployment by the Ethiopians of highly-motivated but poorly-armed civilians in unprecedented human waves of battlefield attacks appears to have forced the TDF to abandon its operations on the southwestern front. A public statement by the TDF military command confirmed the complete withdrawal of the Tigrayans from Afar and a major pullback from Debre Tabor and Debarik.

The TDF claimed these withdrawals and pullbacks were no more than a strategic re- deployment to consolidate their territory. However, Federal and Amhara forces presented it as a major triumph. Soon rumours of an inevitable demise of the TDF and the subsequent recapture of Tigrayan held territories started to circulate. Indeed, after a period of latency when both sides made extensive preparations, the ENDF, Amhara Fano, and Amhara Special Forces launched a series of massive offensives from three directions aimed at capturing Weldia and progressing to Mekelle.

However, Tigrayan forces, who had been well prepared for the anticipated offensives, weathered the storm. Subsequent counterattacks saw the TDF quickly advance to take over Dessie and Kombolcha. The capture of these two strategic cities of South Wollo opened the gateway to Shoa and, with the ENDF seriously weakened, for the first time since the war began, the federal government’s hold on power was threatened.

Tigrayan forces then linked up with Oromo Liberation Front (OLA) to launch offensives on Mille and north Shoa. The attacks on the Mille front, however, proved futile and were repulsed by the ENDF and Afar Special Forces who were provided with aerial cover by drones. To the south, the TDF, joined by OLA, quickly captured areas along the A2 highway and managed to advance as far as Debre Sina.

Nevertheless, coordinated drone attacks on the TDF’s supply lines, the mass mobilisation of Amhara civilians, and concerted diplomatic pressure eventually forced Tigrayan forces to pull back to Tigray’s constitutionally-defined territory.

Ethiopian coalition forces quickly recaptured territories vacated by the TDF and marched all the way to Alamata.

Contrary to high expectations among Abiy loyalists of an imminent ENDF march to Mekelle, as 2021 ended the federal government announced its decision not to advance into Tigray. However, frequent, yet intense fighting continues to be reported on the Tigray/Amhara border.

Below are details of the main operations in the six months of bitter warfare.

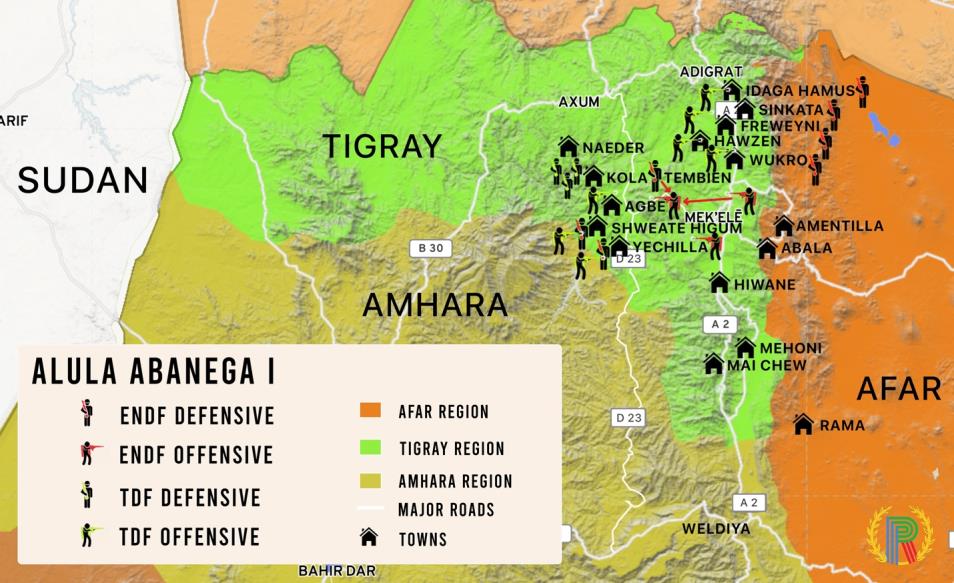

4.2 Operation Alula Abanega

Operation Alula Abanega was the first major Tigrayan offensive that succeeded in reversing the course of the war.

By the beginning of June 2021 there was a huge build-up of ENDF presence in central Tigray. Some sources claimed more than seven divisions of the ENDF were mobilised11. There were widespread rumours of a major Ethio-Eritrean offensive to conclusively defeat the Tigrayan forces before the Ethiopian winter set in. Moreover, it was the week of a national election and there were indications that the federal government was seeking a major battlefield triumph up north to bolster its prospects of an election victory.

The ENDF plan appears to have involved undertaking a huge area in central Tigray, which had hitherto remained a TDF stronghold, and to gradually tighten the chokehold while simultaneously deploying specialised assault units on search-and- destroy missions. It was apparent that the Ethiopian government was determined to “cleanse” every square inch of central Tigray of Tigrayan militants. This, however, required a massive deployment of ground forces as well as accompanying mechanised units on unfamiliar and indefensible terrain, making them susceptible to TDF attack.

The Tigray forces for their part were well aware of ENDF’s impending all-out offensive and were making preparations of their own. By this time, their numbers had grown considerably, reportedly with a huge force organised at corps and army levels. Sources close to the Tigrayan resistance indicated that the TDF had as many as four separate armies at its disposal.

Yet, despite the growing impatience of the Tigrayan public, who were eager for news of a significant victory to lift their spirits, the military command of Tigrayan forces had so far resisted the urge to engage in full-frontal battles, preferring instead to pursue strategies of asymmetrical warfare. Since shifting to the insurgency in December 2020, the TDF’s strategy was to target ENDF weak spots while avoiding direct confrontations. The catchword “attack them at the place and time of our choosing,” often repeated in the central command’s public statements and chanted during army meetings, reaffirmed that the TDF was not about to abandon insurgency any time soon.

This gave crucial time for the TDF command to work on building the army’s capability while wearing down its more formidable enemies. TDF commanders gave interviews during which they highlighted the recent growth in manpower and capability of Tigrayan forces but insisted that it still lacked some essentials for conventional warfare – presumably a reference to the absence of motorised and mechanized units.

The ENDF operation was fundamentally at a disadvantage from the outset as it had very little information regarding its unconventional opponents, and whatever information it had regarding TDF positions and military strength was largely inaccurate. By contrast, Tigrayan generals appeared to have been sufficiently aware of details of ENDF deployments and strength. Ethiopian forces had reportedly assumed the TDF to have no more than 13 inexperienced and unmotivated battalions and had thus adopted lofty plans to complete its defeat of them in a couple of weeks. Grossly underestimating the TDF’s capability had been an ENDF blind spot, but that was not the only one. The Ethiopian forces had assumed the bulk of the Tigrayan army to be concentrated in central Tigray – around Adet, Naeder, and Kola Tembien. According to one high-level TDF commander, the Tigrayans decided to play to ENDF’s expectations and deployed a handful of units around Kola Tembien as decoys to preoccupy Ethiopian forces, while the majority of Tigrayan forces were quietly withdrawn to southcentral Tigray.

On 18 June 2021, Tigrayan forces carried out sudden well-coordinated offensives against Ethiopia’s 11th division which was stretched from Yechilla to Shewate Higum. This was to be the start of “Operation Alula.’ Nearly all Tigrayan forces participated in this offensive that was simultaneously carried out from all directions. Ethiopian prisoners-of-war from the 11th division of the ENDF describe an intense but rapid series of battles during which their units were carved apart by the TDF. The 21st division of the ENDF was sent from around Mekelle to provide support for the 11th division, but faced a well-positioned TDF ambush around Addi Eshir, about 10 km from Yechilla. Similarly, the 31st Division which was deployed around Kola Tembien was mobilised to the rescue but was intercepted by a TDF detachment around Agbe.

The ENDF divisions were prevented from coming to each other’s aid by well- orchestrated and successful TDF offensives. Moreover, the sudden, multi-pronged nature of the TDF attacks, beyond their disorienting effects, over-extended the ENDF frontline causing splits between their units along several nodes. Eyewitnesses described chaotic scenes, with the chain of command completely collapsing, leaving soldiers to fend for themselves.

On 21 June 2021, three and a half days after the start of the offensive, the 11th division was completely neutralised. Many of its heavy artillery weapons, as well as its stores of food and ammunition, fell into the hands of Tigrayan forces. The commander of the division, Colonel Hussain, was captured. The 21st and 31st divisions were also more or less decimated.

Tigrayan forces, which until then lacked mechanised units, were now in possession of scores of heavy artilleries as well as transport vehicles. These were rapidly serviced and put back into service by ex-ENDF operatives, who were protected from harm by the Tigrayan leadership for precisely this purpose.

Not willing to concede defeat, and probably hoping to recover or neutralise the weapons and vehicles they had lost to the TDF, the Ethiopian military leadership apparently decided to overwhelm the area with yet more forces. Accordingly, the 20th, 23rd, 24th, and 25th divisions were reportedly mobilised in quick succession to recapture the area. However, the Tigrayan forces had already familiarised themselves with the terrain, adequately fortified the area, and had further reinforced themselves with their newly acquired weapons and ammunition. The ENDF divisions were walking into a near-certain defeat.

Over three days of fierce fighting, the additional ENDF divisions were routed. In the heat of battle, the TDF anti-aircraft unit shot down a Lockheed C-130 Hercules of the Ethiopian Air Force, further boosting the spirits of the Tigrayans. During the 10-day battle Tigrayan sources claimed around 30,000 Ethiopian forces were neutralised, of whom around 6,000 were taken prisoner.

As the tides were turning in TDF’s favour at Yechilla and Shewate Higum, other Tigrayan forces started to swiftly mobilise to take control of several towns in central and southwestern Tigray. Correspondingly the ENDF began to withdraw from many of these towns, and to concentrate around Mekelle. Consequently, the towns of Hiwane, Mekoni, Hawzen, Freweyni, Sinkata, and Edaga Hamus quickly fell into the hands of Tigrayan forces, largely without fighting. A TDF detachment cut the A2 highway and captured Wukro which reportedly left a brigade-sized ENDF unit isolated and surrounded near Negash.

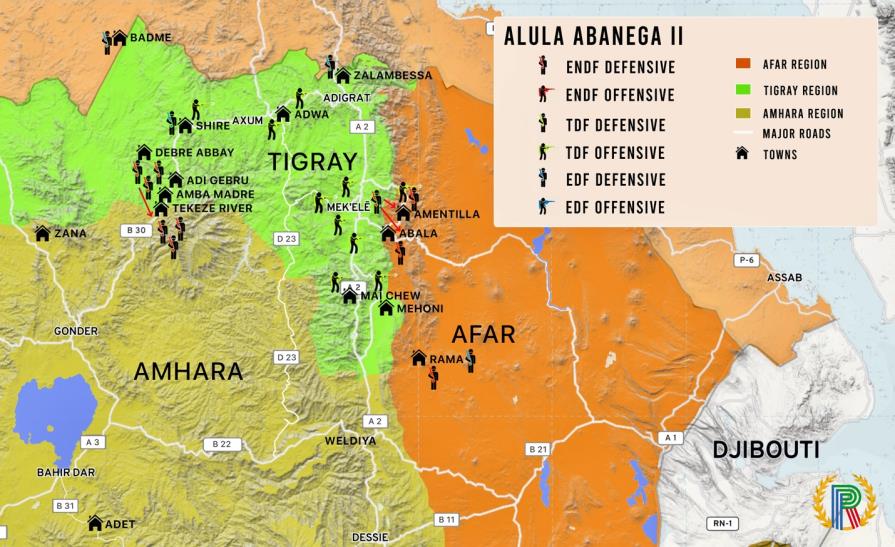

The reaction of the Eritrean army to the ENDF losses was unexpected, to say the least. Eritrean Defence Force (EDF) units situated around Shire were initially included in the ENDF plans and were supposed to complete the encirclement of Tigray between Zana and Adet, as well as to carry out offensives towards central Tigray. But since the Tigrayans had withdrawn most of their forces to participate in the fighting further south, the Eritreans did not participate in the Ethiopian planned encirclement of central Tigray.

What is more significant is the apparent reluctance of the EDF to provide the Ethiopian army with a crucial lifeline when it was facing devastating losses around Yechila. Some Tigrayan sources have claimed that a few brigades of the EDF were indeed mobilised to come to the rescue of their allies but were intercepted by TDF detachments placed at key junctions, forcing them to abandon their plans. The EDF’s lack of determination to come to ENDF’s rescue was probably caused by fear of sustaining defeat similar to that inflicted on their Ethiopian allies. Self-preservation had kicked in.

The crunch came on 28 June 2021. As Tigrayan forces, who had already taken control of much of the surrounding area, approached Mekelle from several directions, the Tigrayan political leadership which had been put in place by Prime Minister Abiy, were airlifted out of the regional capital to the midlands. Ethiopian forces garrisoned inside the city withdrew, amidst visible chaos, taking everything, they could carry with them.

Tigrayan forces entered Mekelle to a rapturous welcome. As most of the A2 highway, both to the north and south of Mekelle, had fallen into the hands of Tigrayan forces, the ENDF hastily retreated to the east heading for the Afar region through the border town of Abala. However, Tigrayan forces claimed to have caught up with them near Amentilla and allegedly inflicted significant losses.

The ENDF and EDF withdrawal from much of central and southern Tigray accelerated after the fall of Mekelle. The very next day, Tigray forces quickly entered Adwa, Axum, and Shire to the northwest. To the south, the TDF’s advance continued as far as Mehoni and Mai Chew.

The federal government said its unexpected withdrawal was due to its decision to declare an immediate and unilateral ceasefire, in response to a request from the Tigrayan interim administration that it had installed, and to allow the delivery of humanitarian aid. The ceasefire, it claimed, was to last until the farming season ended. The Tigray forces however rebuffed the federal government’s claims and insisted that major battlefield defeats had forced Ethio-Eritrean forces to flee.

The Eritrean army also withdrew its forces without major clashes from most of central Tigray and established defensive fortifications around the border. However, it retained several areas in the northeast, including large towns such as Rama and Zalambessa, as well as Badme.

Similarly, Amhara forces, which had established a presence in central Tigray around Debre Abay and Adi Gebru, retreated to the other side of Tekeze river, what the Amharas consider their traditional boundary with Tigray. Moreover, they established defensive positions near Amba Madre and destroyed the Tekeze bridge connecting Amba Madre with Adi Gebru, probably to prevent the pursuit of Tigrayan forces. All territory to the west and south of the Tekeze remained firmly under the control of ENDF and Amhara forces.

In rapidly withdrawing from much of central and southern Tigray and establishing defensive lines in areas claimed by the Amhara regional state, Ethiopian forces made their intentions clear. Having failed to root out the TDF from central Tigray, and after sustaining one of the biggest battlefield losses in recent Horn of Africa history, the ENDF’s plan B was containment. It would make its stand among the people Abiy Ahmed identified as ENDF-friendly, in contrast to the people of Tigray who were deemed “hostile.”

Consequently, Ethiopian, and Eritrean forces rapidly vacated most of the territories of Tigray except for the contested areas. They established a wide envelopment around central and southern Tigray in an attempt to strangle the resistance into submission. Banking, telecommunications, and electricity, were among the services that were discontinued soon after the ENDF withdrawal. Humanitarian aid delivery became increasingly scanty and politicized. The Prime Minister, in his public statement after the ENDF’s withdrawal, explained the reason behind the federal government’s decision as a determination not to repeat the Derg’s mistake12.

“The main reason why Woyane [the Tigrayans] defeated the Derg during the war of ‘Ethiopia first’ was by using the Derg’s weapon and food. So, given the current situation, if we stay there for long, we are going to provide them with many weapons. When it comes to food [aid], if one family has five children, they register that they have 7, 8, or 10 children. Then they receive the rations of ten. They use five of it themselves and give the remaining five to the Junta… So, we discussed this issue for a week and decided not to accept this any longer.

Abiy made it clear in no uncertain terms his intentions to politicise the delivery of humanitarian aid into Tigray. A senior UN official later conceded that starvation was being used as a weapon while OCHA, a UN humanitarian agency, described the situation in Tigray as a ‘de facto aid blockade’13.

The TPLF, for its part, quickly re-established its administrative structure after re- entering Mekelle. Key political figures, such as Debretsion Gebremichael, who had remained hidden since the start of the insurgency, made a triumphal entry to the city. The regional House of Representatives resumed its sessions.

The newly re-established TPLF-led Tigray administration soon made its rejection of the federal government’s ‘unilateral ceasefire’ public. It claimed that the Addis Ababa regime was in fact, under guise of a ceasefire, enforcing a siege on the people of Tigray, and announced its determination to break the siege through force if necessary.

4.3 Operation Tigray Mothers

Operation Tigray Mothers consisted of phased offensives which took the battle to protect Tigray into surrounding areas, some of them annexed in previous conflicts.

Phase 1: TDF offensive to retake annexed territories

It became increasingly clear that the ceasefire wasn’t going to hold, and the Tigray forces were going to launch an offensive. The question was in which direction? Western Tigray was obviously the big prize as it would open up the crucial corridor to Sudan that would be vital for supplies. But the Ethio-Eritrean alliance was fully aware of its importance and was determined to prevent TDF penetration into western Tigray at all costs. Consequently, large detachments of the EDF and ENDF were deployed in the area along with several lines of trenches and minefields. Moreover, tens of thousands of Fano and Amhara militia, mainly from Gondar, were mobilised into the area and entrenched there to provide reinforcements. The flat terrain of western Tigray favoured the Ethio-Eritrean forces with superior firepower. The ENDF’s in depth defence along with extensive artillery support would spell disaster for TDF operations in the area. Consequently, although there were unofficial reports of skirmishes, probably involving TDF reconnaissance units, around Adi Remets, the anticipated large-scale TDF operation to western Tigray did not materialise.

There was also a brief anticipation that the TDF might take advantage of its winning momentum, as well as the EDF’s disorganised retreat, to go north. But any plans the Tigrayans might have had to confront the Eritrean army were shelved, at least temporarily, probably for the same reason as the decision to abort a military operation into western Tigray.

Contrary to expectations, TDF offensives focused on regaining lost territories on the southwestern and southern fronts. Preparations were relatively quick for operations of such a magnitude. It seemed the Tigrayan military command didn’t want to lose momentum. The Tigrayans had acquired significant quantities of heavy artillery during their successes in central Tigray and had been able to form multiple mechanised units that could support conventional offensives, which were rapidly launched.

On 12 July 2021, a massive series of offensives, dubbed ‘operation Tigray Mothers’, were launched on both fronts. On the southern front, the TDF’s immediate objective was to capture Korem and Alamata. The Ethio-Amhara defensive line was on and around Grat-Kahsu, a strategic mountain range near Korem, which made a southward offensive along the A2 highway nearly impossible.

Tigrayan combat forces, instead of going straight for Korem, which would have put them at a disadvantage, made their primary direction of attack to the east, mobilising from areas around Chercher to take Bala and Ger Jala towns, before arcing around to launch an offensive on Korem from the rear. Fighting in the vicinity of Korem was very intense and lasted an entire day. Both sides were said to have suffered heavy losses. Amhara sources reported that Tigrayan forces encountered strong resistance from the ASF and that the initial offensive was repulsed. The relatively unexpected direction of the TDF attack had threatened to cut off large sections of the defending force. Consequently, faced with the inevitable fall of Korem, the ENDF command ordered their remaining forces to withdraw past Alamata and set up a new fortification near the more defensible Kobo.

The capture of Grat Kahsu meant the TDF had artillery control over Alamata and surrounding areas, which in turn forced the ENDF and its allies to give up the capital of southern Tigray without a fight. The TDF entered Alamata on 13 July 2021, and then quickly retook areas as far as Waja. This meant that after several months under occupation of Amhara forces, the contested territories of southern Tigray were back under the control of Tigrayan troops.

On the southwestern front, TDF offensives were aimed at capturing Amba Madre and Mai Tsemri towns. Even prior to the start of operation Tigray Mothers, Amhara sources had claimed that a small-scale TDF attack was repulsed around Amba Madre. This meant Tigrayan reconnaissance units had already crossed the Tekeze river and secured safe zones on the southern bank. On 12 July 2021, Tigrayan infantry units swam through Tekeze river at several places. To the east the TDF offensive focused on driving out Amhara forces from Fiyelwiha and the surrounding Dima district. Similarly, a well-coordinated TDF attack from several directions succeeded in breaking through ASF and ENDF defensive lines near Amba Madre. The next day, Amba Madre, Mai Tsemri, and Fiyelwiha were captured. Tigray’s southwestern territories were now back under Tigrayan control.

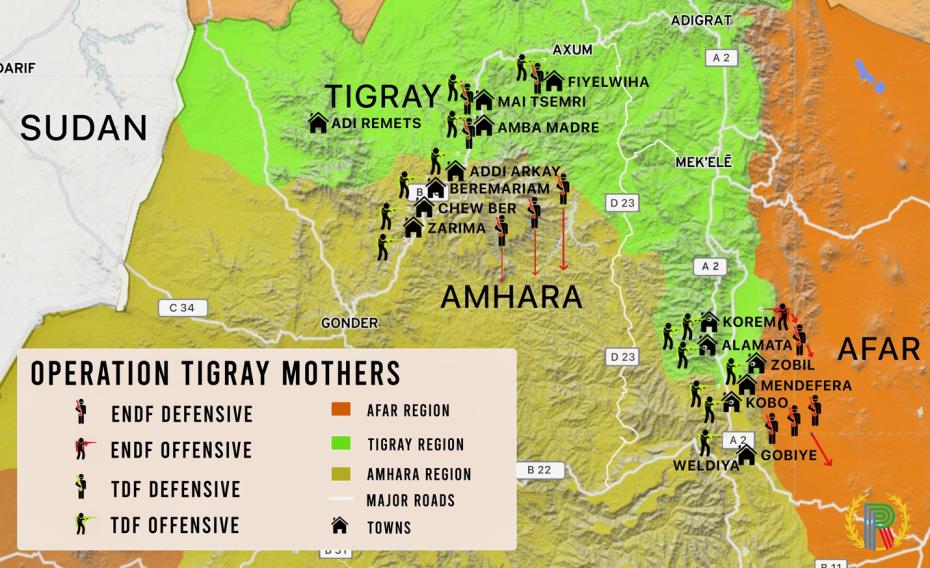

Phase 2: Expansion of the war into Amhara and Afar regions

Southern Front: TDF operation on Kobo

The TDF’s victory in the first series of conventional battles sent shockwaves through the Ethiopian and Amhara leadership. A day after Tigrayan forces captured Alamata and Mai Tsebri, PM Abiy Ahmed released a statement that basically revoked the declaration of unilateral ceasefire and called on Ethiopians to support the national army14. Regional administrations responded with ceremonies mobilising their special forces and sending them off to the battlefront. Footage of these was carried on national television, emphasising the federal government’s backing from all of Ethiopia’s regional states, as well as the public. The war against the TPLF was portrayed as a national, patriotic endeavour.

Tigray’s leadership, on the other hand, made it clear that it didn’t have any intention of stopping its offensives as long as the de facto siege of the region remained in effect and Amhara forces and ENDF occupied western Tigray.

Fighting along the Tigray-Amhara border intensified from 16 July 2021. The TDF deployed several infantry and mechanised divisions in an attempt to penetrate the eastern border and take control of the Zobil heights. Located along the border between Amhara and Afar regions, Zobil mountains, with an estimated elevation of over 2000 metres, separates the broad fertile plains of Raya Kobo from the lowlands of the Afar region.

The ENDF and Amhara forces primarily concentrated their defence around Chube Ber, a few kilometres north of Kobo. Moreover, heavy artillery batteries of the ENDF were established around Gira’amba Lancha, Mendefera, and Chube Ber from where they conducted a relentless bombardment of the mountainous terrain north of Zobil. According to a TDF commander, this was followed by a series of counter-offensives by the ENDF to cut off and neutralize the bulk of TDF units that had concentrated near Zobil heights. TDF detachments which had been well placed in strategic areas in anticipation of such attacks managed to halt the ENDF counterattacks. An ensuing TDF offensive eventually breached the defensive lines of Amhara forces on the Zobil heights and took control of the strategic mountain range. Subsequently, the Tigrayan forces quickly moved around Mendefera district and severed the Kobo-Woldiya Road around Aradum, thereby blocking off a means of retreat for several battalions of the ENDF that were left stranded at Chube Ber. An attempt by the now isolated Ethiopian forces to withdraw to Lalibela through Ayub was also blocked and eventually neutralised by another TDF detachment which was positioned for that purpose resulting in a massive loss for the ENDF. On 23 July 2021, Tigrayan forces took control of Kobo town. In the meantime, another detachment advanced further south and took control of Kobo Robit and Gobiye, with minimum resistance from retreating Ethiopian forces.

Southwestern front: the TDF advance towards Gondar

After initially being forced to retreat from Mai Tsebri by determined resistance from Amhara forces, the TDF launched a successful counteroffensive enabling it to penetrate into North Gondar Zone of the Amhara region and capture Addi Arkay on 23 July 2021. General Tadesse Worede, commander of the TDF, claimed that the terrain had made their advance very challenging. Indeed, the presence of several easily defensible commanding heights on one of the most mountainous areas of northern Ethiopia put the advancing force at a distinct disadvantage. However, rugged and mountainous terrain also prevented large-scale battles and reduced the impact of the ENDF’s superior firepower.

In addition, the TDF’s general strategy of mobilising smaller units and launching coordinated attacks from several fronts, enabled it to isolate and overcome pockets of Amhara resistance. Consequently, Tigrayan forces advanced rapidly deeper into the area north of Gondar and within the space of three days, seized Beremariam, Chew Ber, and Zarima towns.

Afar front: TDF push towards Chifra

At about the same time as Tigrayan forces were locked in fighting to capture Kobo, another army-sized TDF detachment crossed into Yalo woreda of Afar region and waged a major offensive against the ENDF and Afar Forces. There was already a heavy build-up of federal and regional forces in the area, which, in the eyes of the Tigrayan leadership, was in preparation for a renewed invasion of Tigray. The flat landscape of the Afar region meant that the TDF had to deploy a sizeable percentage of its infantry against ENDF defensive lines on open ground, making it vulnerable to the opponent’s superiority in firepower and numbers.

This also meant that the TDF infantry risked sustaining much higher casualties inflicted by ENDF heavy artillery batteries, which were superior to anything the Tigrayans had at their disposal. The absence of rugged terrain meant that Tigray forces were not able to deploy their favoured strategy of carving up enemy forces piecemeal and compelled them to face the massively entrenched infantry of ENDF in a full-frontal battle, where numerical superiority counted. The ENDF’s extensive use of air raids also compounded the challenge.

However, an attack on the right flank, coordinated with a massive frontal assault, reportedly destabilised ENDF lines and ended up in another TDF victory. By 23 July, the TDF had captured Yalo, Golina and Awra Woredas of Zone 4 penetrating deeper south, to within a few kilometres of Chifra. In the course of their advance Tigrayan forces claimed to have completely destroyed the 23rd division of the ENDF and seized large quantities of heavy and medium-sized weapons.

The TDF’s successes in the Afar region were deemed so significant by the Tigrayan leadership that the next day General Tsadkan Gebretensae, a member of the central command, reportedly said, “The TDF can move swiftly to control the Addis Ababa- Djibouti Road and will be in a position to accept humanitarian assistance directly.”15

On 26 July 2021, General Tadesse Worede, TDG commander, announced the successful conclusion of “Operation Tigray Mothers.”16 It was apparent that, though the fighting was still ongoing, the Tigray military leadership believed it had inflicted enough damage on its adversary to achieve the primary objective of the operation – containing the ENDF’s threat of re-invasion.

It had set out to nullify what it saw as an impending ENDF offensive from Gondar, Wollo and Afar. The TDF’s official statement claimed to have neutralised over 30,000 Ethiopian forces17. Political analysts, who closely followed the progress of the war, agreed that the ENDF capability had been seriously compromised due to its major losses, especially in Tembien and Kobo.

Moreover, a staggering quantity of heavy and light weaponry fell into the hands of the Tigrayans. This was enough to transform it into a well-equipped army with a greatly enhanced combat capability. The spoils of war, combined with its highly- experienced military leadership at all levels, and the ex-ENDF weapons operators it had at its disposal, had turned the TDF into a formidable military force that was now a real threat to both Addis Ababa and Asmara.

The response from the Ethiopian side also reflected just how seriously the national army had been affected. Agegnehu Teshager, vice president of Amhara Regional State, made an unprecedented call to “all young people, militia, non-militia in the region, armed with any government or personal weapons, to join the war against TPLF”18.

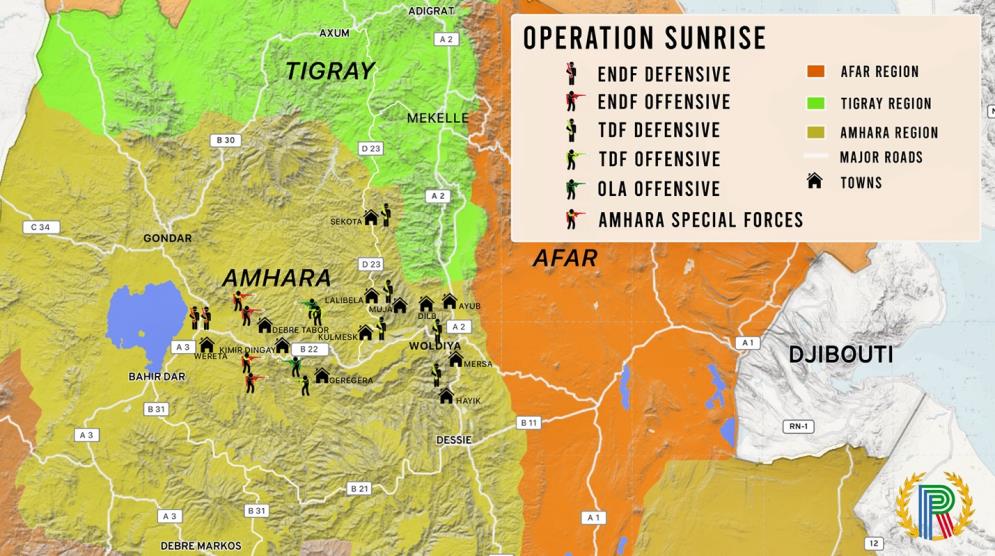

4.4 Operation Sunrise

Tigray forces maintained their offensives on all fronts but now with a new operational title “Operation Sunrise.” By August 2021, the Tigrayan central command appears to have believed that it had sufficiently degraded the military capabilities of its adversaries to have a go at the capital. The name “Sunrise” hinted that the TDF’s objectives had evolved to include possible regime change.

Southern front: Gobye to Meket

The TDF continued its advance down the A2 highway relatively unchallenged, until it reached the gates of Woldiya. Much to the indignation of the town’s residents, ENDF detachments were ordered to withdraw from Woldiya without a fight, choosing instead to retreat to the hills to the south, between Woldiya and Sirinka, to try to halt the TDF’s advance.

In the vicinity of Woldiya, Tigrayan forces encountered determined resistance from local militia and Amhara Fano militia, led by the town’s mayor, who called upon every able-bodied person to fight, and the residents appeared determined not to let their hometown fall into the hands of the Tigrayans. After several days of skirmishes outside the town, during which both sides were reported to have used artillery, the TDF finally took control of Woldiya on 9 August 2021.

Woldiya’s popular resistance was widely promoted by the Amhara government and political activists as a model of urban resistance, to be replicated by other towns of Amhara region that faced the threat of TDF occupation. The residents of Debre Tabor and Debarik organised similar urban resistance, which played no small part in staving off an TDF advance.

The battle of Woldiya-Sirinka was the biggest engagement along the A2 highway since Kobo. According to Tigrayan sources it involved two ENDF divisions, more than 11,000 Oromo Special Forces (OSF), Amhara Fano, ENDF special Commando battalions, and mechanized divisions. TDF also reportedly deployed, among others, its ‘Remets’ and ‘Maebel’ divisions. After a fierce encounter, Tigrayan forces emerged victorious, amassing large quantities of heavy and medium weapons. Video footage of the aftermath, aired on Tigray TV, showed scores of ENDF vehicles and weapons destroyed or captured.

By the end of August, after facing sporadic resistance around Mersa, Tigrayan forces had penetrated as far as the rural areas around Hayik, a town 28 km from Dessie.

Opening a new front

Towards the end of July, another battlefront had already opened up to the west of Kobo. Several TDF divisions had advanced to the southwest, probably via a byway through Ayub, encountering only Amhara forces along the way. By the beginning of August, Tigrayan forces had advanced rapidly and were already in control of Muja and Kulmesk towns. From there they rapidly advanced northwest and, after a period of sporadic fighting with Amhara forces, took control of the historic town of Lalibela. Capturing Lalibela denied the Ethiopian Air Force decisive access to Lalibela’s strategic airport, which it had been using extensively to support the ENDF’s ground assault around North Wollo and Wag Himra.

Part of this TDF detachment then moved from Muja southeast to Dilb, where it sought to sever the Woldiya-Woreta Road. After reportedly sweeping away the massive ENDF detachment entrenched around Dilb it advanced in the direction of Woldiya, as far as Sanka. To the east of Dilb, TDF forces made a rapid advance along the B22 highway and captured the strategic towns of Gashina and Geregera, as well as all the towns in between. It appears that at least part of the detachment that captured Lalibela was re-routed via Dubko, a small town along a secondary road connecting the Lalibela to Muja route with the B22 highway, to take part in the capture of the strategic town of Gashina. Hence, by mid-August, the TDF had already taken control of most areas of North Wollo and was advancing along the B22 towards neighbouring Lay Gayint woreda of South Gondar Zone.

By this time, it was apparent that the objective of TDF operations along the B22 highway was to sever the Bahir Dar-Gondar Road at the strategic town of Woreta which, if successful, would choke off the supply line to the northwest, putting the entire Ethiopian western command in jeopardy. Determined not to let this happen, the Ethiopian coalition deployed a huge force, including several divisions of the standard army and Amhara Special Force, in the highly mountainous area between Nifas Mewcha and Kimir Dingay. A two-day brutal battle that started on 15 August 2021 culminated in a major defeat for the Ethiopian side and enabled the TDF to establish control all the way to Kimir Dingay. Moreover, Mount Guna, the most strategic high ground located a few kilometres from Kimir Dingay, came under the control of Tigrayan forces. This crippled ENDF chances of mounting a meaningful resistance as far as Debere Tabor.

Meanwhile, a new front opened up to the northwest, as Tigrayan forces, in alliance with a few battalions of the newly formed Agaw Liberation Army (ALA) (which drew its support from ethnic Agaw populations in Wag Himra and Agew Awi Zones of Amhara region) attempted to wrestle control of Sekota from the hands of Amhara SF. The TDF-ALA offensive reportedly took place around mid-August as a joint TDF- ALA detachment advancing from Korem, was joined by another TDF detachment from Lalibela. By 17 August 2021, Sekota, the capital of Wag Himra zone came under the control of TDF-ALA troops.

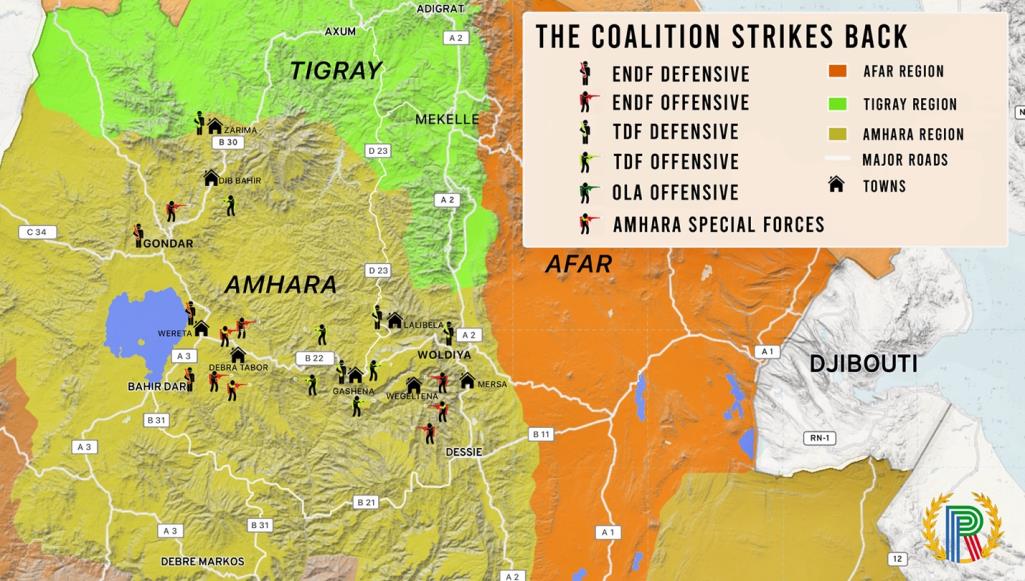

4.5 The Federal Government Coalition strikes back

However, it wasn’t long before the coalition of ENDF and their allies struck back in offensives with fluctuating results until the end of 2021.

Firstly, from mid-August, they launched well-planned, massive counteroffensives on several fronts in an attempt to reverse TDF gains. On the 19 August 2021, as the TDF was making preparations to take Debre Tabor, Ethiopian coalition forces launched a major counteroffensive that aimed to slice through and surround the bulk of TDF detachments in Lay Gayint and South Wollo. One Ethiopian counteroffensive involved a sizable detachment of ENDF and Amhara forces which were mobilised from Wegeltena to capture Gashina and thus cut off the supply route of the huge Tigrayan detachment that was heading for Wereta. Another ENDF counteroffensive sought to break through at Sirinka, to destroy a large proportion of the TDF that had gathered around Mersa. Tigrayan sources claimed that on the Gashena front alone, as many as five divisions of the ENDF and more than 10,000 Amhara forces, took part in the counteroffensive. The encirclement of the TDF detachment encamped around Mersa involved several brigades of the elite Republican Guard, Special Commando, Federal Police forces as well as the militia of South Wollo. The plan was for specialised assault units to surround and neutralize the enemy.

It appears that the ENDF plan initially worked. Gashina was captured and the B22 highway was severed leaving the bulk of Tigrayan forces in Gayint and Debre Tabor with no way out. Similarly, the Woldiya-Mersa road was severed at Sirinka leaving TDF’s southern detachment stranded.

However, TDF detachments soon converged on the Ethiopian forces occupying Gashina from three sides: from Arbit [Debre Tabor], Dubko [Lalibela], and Istayish [Woldiya]. After at least two days of intense and brutal fighting in which both sides suffered immense losses, the Ethiopian forces retreated towards Kon. Similarly, Tigrayan forces were also able to repel the Ethiopian forces from Sirinka and reconnect with their units in Mersa.

Towards the end of August, ENDF and Amhara forces began a series of counter- offensives on the southwestern front that intensified through the early days of September. By this time, the TDF had reached Dib Bahir, near the great escarpment of Limalimo. Moreover, TDF reconnaissance units had penetrated the rural areas of North Gondar as far as Dabat. However, numerous “human wave” attacks, involving large, mobilised units of local militia and barely-armed farmers, became a formidable challenge to the TDF’s advance. At least one counter-offensive on Tabla, between Dib Bahir and Zarima, involving several brigades of ENDF units attempted, but allegedly failed, to cut off TDF forces deployed south of Dib Bahir. The Chenna massacre, where more than 100 civilians were allegedly massacred by TDF units in retribution for guerrilla attacks, was also reported at this time19. It was increasingly apparent that the TDF was finding it ever harder to sustain its advance on Gondar.

All in all, even though the Tigray’s army command was able to save most of its forces, which had become stranded and faced annihilation, it was nevertheless forced it to relinquish significant parts of the hard-fought territorial gains on Woreta- Woldiya and Gondar fronts. Subsequently, Tigrayan forces under sustained offensives by local militia and ENDF units rapidly withdrew from Debre Tabor and Lay Gayint. They retreated all the way to the edge of North Wollo and concentrated around Filakit and Gashena. Eventually, the TDF operation to take Wereta and sever the Bahir Dar – Gondar highway was abandoned. Similarly, the TDF’s rapid advance towards Gondar came to a grinding halt around Dib Bahir and Tigrayan forces were eventually forced to retreat to Zarima.

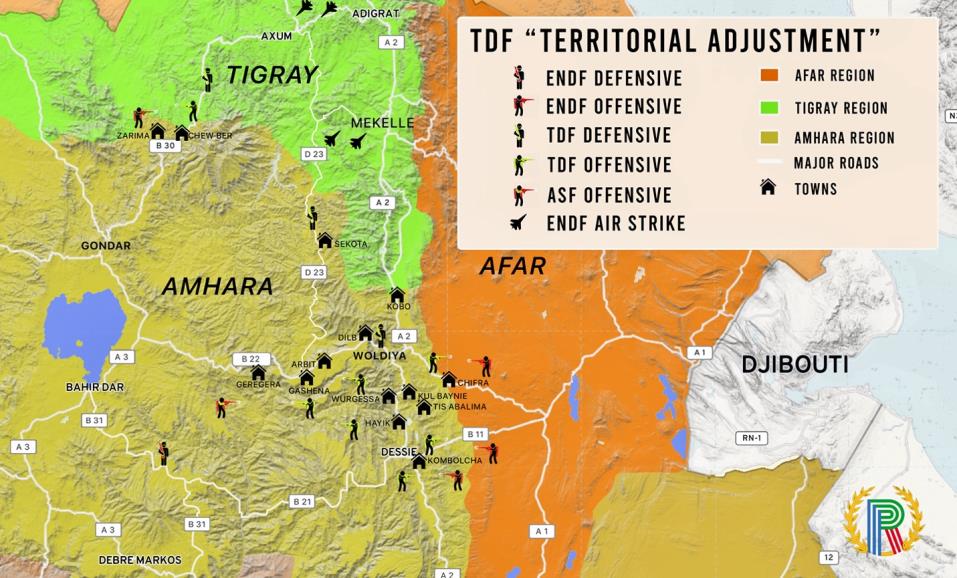

4.6 TDF “Territorial Adjustment” and “Recalibration”

On 9 September 2021, the TDF released a statement announcing that it has decided “to make limited territorial adjustments temporarily from areas it had been in control of”20. It was apparent that the Tigrayans were finding it increasingly difficult to sustain their control of some of the less defensible areas of Amhara and Afar. The TDF gave two main reasons for its decision: Amhara region’s mass mobilisation of barely trained civilians “in hundreds of thousands,” who were then used in human wave attacks, and the deployment of Eritrean forces “to rescue Amhara forces”21.

The former implied that the Amhara region’s mass mobilisation strategy had borne fruit. Moreover, there were unofficial reports of local insurgencies around Kobo and north Gondar emerging from rural areas that had been largely left unoccupied by the Tigrayans. These were obviously causing problems for TDF supply lines, making further advances difficult. In addition, there were unofficial reports from Tigrayan sources of a significant level of EDF deployment in Gondar and Dessie aimed at protecting the two important cities from falling into TDF hands. Nevertheless, the EDF’s involvement in Amhara region has so far not been independently verified.

Following the announcement, Tigrayan forces made further withdrawals including a complete pull-out from Afar. Moreover, Ethiopian sources confirmed TDF retreats from Flakit and Gashina on the Woldiya-Woreta front; from Hayik on the Dessie front; from Sekota and its surrounding on the Wag front; as well as from Zarima and Chew Ber on the north Gondar front.

The failure of ENDF’s ‘irreversible offensive’ and TDF’s advance to Dessie

By the beginning of October, reports started to emerge that Ethiopian forces had planned a massive offensive across the Amhara region. Abiy’s government had just been formally inaugurated following his election victory and was apparently determined to assert its power with some solid gains on the battlefield. An Amhara regional official spoke of an impending “irreversible operation” to be carried out “on all fronts”22.

On 8 October 2021, major air and ground offensives were launched by the combined ENDF and Amhara forces around Geregera, Wegeltena, Wurgessa, and Haro. The main objective of the operation seemed to be to capture Woldiya and Kobo with a possible advance further north. From the Haro front, an ENDF detachment was mobilised from Arerit probably aiming to enter Woldiya from the northeast. Similarly, a major offensive was launched at Geregera intended to advance along the B22 highway all the way to Dilb and then descend to Woldiya. In the meantime, another ENDF and Amara detachment was carrying out a comprehensive offensive in Wegeltena, ultimately aiming to cut off the Woldiya-Gashena Road at Dilb by advancing across the high hills of the Ambasel range to the northwest. This would cut the TDF’s supply route to Gashina and isolate the Tigrayan forces at Geregera and Gashena. On the Wurgessa front, ENDF and Amhara coalition forces attempted a major penetration and assault along the A2 highway in an attempt to break through TDF fortifications around Mersa and advance to Woldiya.

After several days of intense and brutal fighting on all fronts, it was becoming increasingly clear that the ENDF offensives were not achieving their objectives. By 12 October 2021, after four days of fighting, no appreciable progress had been made by coalition forces, apart from a few gains around Arbit of Gashena front. Around this time, Getachew Reda, spokesperson for the Tigray government, claimed that the ENDF had suffered “staggering losses” and General Tsadkan, a member of TDF’s central command, predicted: “I don’t think this will be a protracted fight – a matter of days, most probably weeks. The ramifications will be military, political and diplomatic”23. It was apparent that the Tigrayan side was confident that it had inflicted significant damage on its adversary and that the ENDF’s offensives had all but failed.

On 12 October 2021, after absorbing waves of ENDF’s offensives for several days, the TDF launched its counterattacks. Emboldened by the ‘staggering losses’ the Ethiopian forces suffered during its offensives, the objectives of TDF counterattacks were predictably ambitious: capturing of the strategic cities of Dessie and Kombolcha.

Brigadir General Haileselassie Girmay, one of the commanders in charge of Tigray’s forces on the southern front revealed24 that the TDF had executed an attack from four directions to take Dessie. One TDF detachment moved from around Faji and Kul Bayine toward Tis Abalima and by following the hills to the east of the A2 highway took a turn to the right of Haiq lake and advanced on Tita. Another detachment mobilised from the TDF stronghold around Mersa and kept a course to the west of the A2 highway all the way to Marye heights and then turned to Kutaber. Another “piercer” detachment moved down the middle, along the A2 highway, between the two adjacent TDF offensive units. It sought to destroy the ENDF’s multi-layered and dense entrenchments at Sudan Sefer, Wuchale and Wurgessa and then to progress towards Borumeda. To the far west, another TDF detachment, which had neutralised Ethiopia’s forces around Wegeltena, advanced to the southeast and converged with the TDF detachment from Marye. The two then co-ordinated their assault with the piercer division to mount an attack on the ENDF’s base at Borumeda. The triad then headed straight for Dessie.