Source: The Atlantic not Substack.

After the US election last November, I changed my plans.

For many years, I had been writing about America, Europe, Russia and Ukraine, describing and analyzing the breakdown of international norms, the spread of authoritarian propaganda, deliberate attempts to create refugees and violence. I knew that Trump’s victory ensured that these geopolitical shifts, away from the rule of law and towards a more anarchic world, would become permanent. Of course I would continue about what that means for Americans, for Europeans, for Ukrainians. But I also wanted to look at the problem differently. How does this shift look from elsewhere? What does the post-American world look like from Sudan, for example, where a civil war has displaced more people than in Ukraine and Gaza combined?

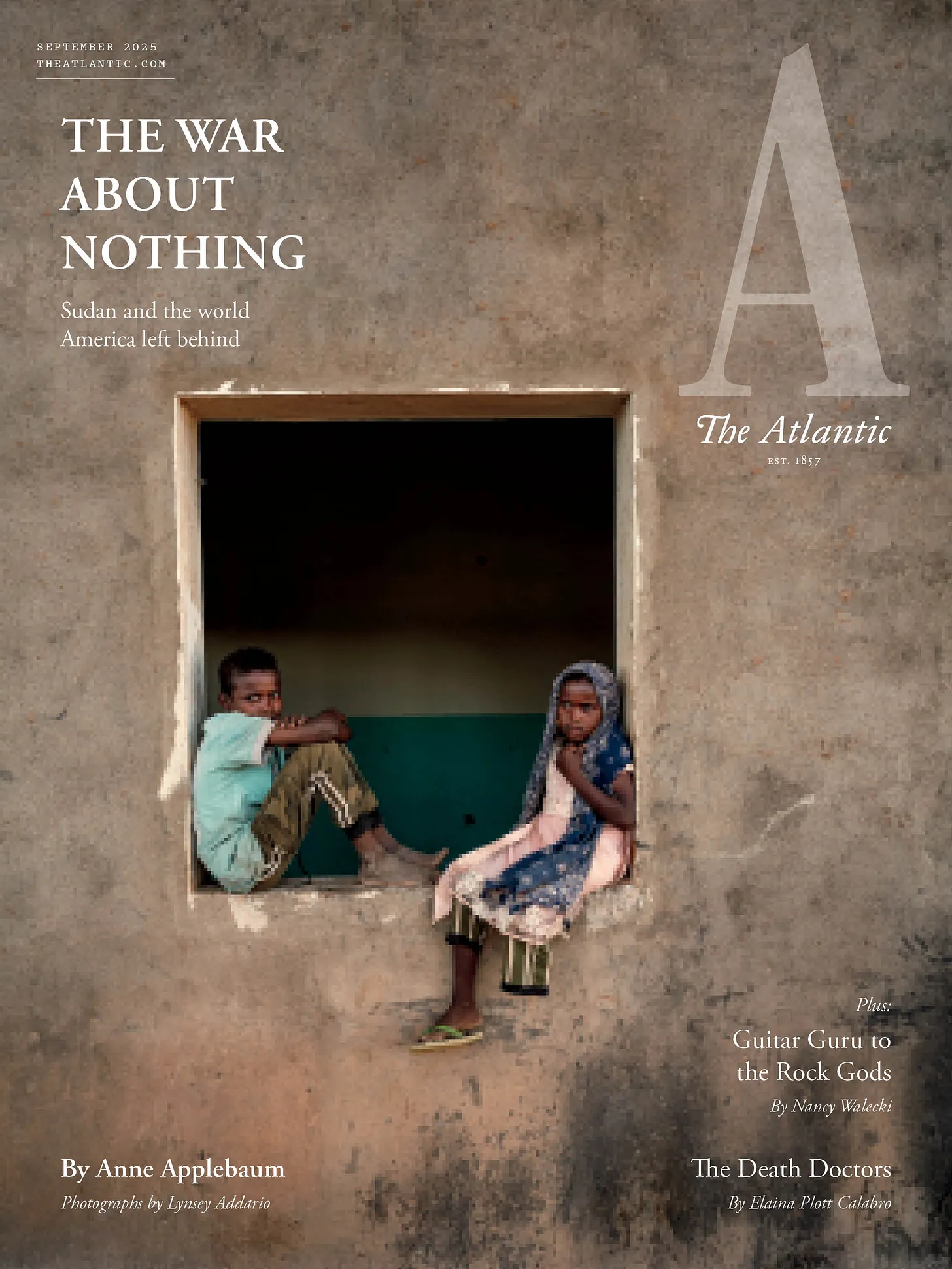

I made two trips to the region, to both sides of the main frontline. The first time I crossed the border into Sudan from Chad, escorted by the Rapid Support Forces, the militia group who occupy Darfur. The second time I flew via Dubai into Port Sudan, on the coast, and then drove to Khartoum—it’s about a twelve-hour drive across the desert—with an official from the Sudanese armed forces and the photographer Lynsey Addario.

On both trips, I saw what happens when the state disappears. Sudan is now in its third year of a civil war that seems to have no point, no purpose, and no end. Like a tsunami or a hurricane, the war has left wide swathes of physical wreckage in its wake, and human damage too. Food is scarce. The education system has collapsed. International institutions are weak. And, as it turns out, when you take away the liberal world order, you don’t get something better. Instead, you get anarchy, nihilism, and a war fueled by outsiders – Saudi, Emirati, Turkish, Egyptian, Russian, Iranian – and a scramble for Sudanese gold.

The first section of the article follows, but please read the whole thing: it takes time and space to tell the full story, to explain the history and background, and the article is designed for people who don’t necessarily know much about Sudan at all. Of course I am not just writing about geopolitics: Sudan has a specific history that matters. Also, if you read the full story, either on the website or in the physical magazine, you can see all of Lynsey’s amazing photographs.

While you are at it, subscribe to the Atlantic. Without their support, I couldn’t have made these trips. My editors supplied not just airplane tickets but security advice, GPS trackers, even energy bars. Not all journalism can be written from your home office, or any office. Also, I have lots of great colleagues, and you can read them too.

This is What the End of the Liberal World Order Looks Like

In the weeks before they surrendered control of Khartoum, the Rapid Support Forces sometimes took revenge on civilians. If their soldiers lost territory to the Sudanese Armed Forces during the day, the militia’s commanders would turn their artillery on residential neighborhoods at night. On several consecutive evenings in March, we heard these attacks from Omdurman, on the other side of the Nile from the Sudanese capital.From an apartment that would in better times have been home to a middle class Sudanese family, we would hear one explosion. Then two more. Sometimes a response, shells or gunfire from the other side. Each loud noise meant that a child had been wounded, a grandmother killed, a house destroyed.

Just a few steps away from us, grocery stores, busy in the evening because of Ramadan, were selling powdered milk, imported chocolate, bags of rice. Street ven dors were frying falafel in large iron skillets, then scooping the balls into paper cones. One night someone brought out folding chairs for a street concert, and music flowed through crackly speakers. The shell ing began again a few hours later, probably hitting similar streets and similar grocery stores, similar falafel stands and similar street musicians a couple dozen miles away. This wasn’t merely the sound of artillery, but the sound of nihilism and anarchy, of lives disrupted, businesses ruined, universi ties closed, futures curtailed.

In the mornings, we drove down streets on the outskirts of Khartoum that had recently been battlegrounds, swerving to avoid remnants of furniture, chunks of concrete, potholes, bits of metal. As they retreated from Khartoum, the Rapid Support Forces—the paramilitary organization whose power struggle with the Sudanese Armed Forces has, since 2023, blossomed into a full-fledged civil war—had systematically looted apartments, offices, and shops. Sometimes we came across clusters of washing machines and furniture that the thieves had not had time to take with them. One day we followed a car carrying men from the Sudanese Red Crescent, dressed in white hazmat suits. We got out to watch, handkerchiefs covering our faces to block the smell, as the team pulled corpses from a well. Neighbors clustered alongside us, murmuring that they had suspected bod ies might be down there. They had heard screams at night, during the two years of occupation by the RSF, and guessed what was happening.

Another day we went to a cross ing point, where people escaping RSF occupied areas were arriving in Sudanese army-controlled areas. Riding on donkeycarts piled high with furniture, clothes, and kitchen pans, they described a journey through a lawless inferno. Many had been deprived of food along the way, or robbed, or worse. In a house near the front line, one woman told me that she and her teenage daughter had both been stopped by an RSF convoy and raped. We were sitting in an empty room, devoid of decoration. The girl covered her face while her mother was talking, and did not speak at all.

At al-Nau Hospital, the largest still operating in the Khartoum region, we met some of the victims of the shelling, among them a small boy and a baby girl, Bashir and Mihad, a brother and sister dressed in blue and pink. The terror and screaming of the night before had subsided, and they were simply lying together, wrapped in bandages, on a cot in a crowded room. I spoke with their father, Ahmed Ali. The recording of our conversation is hard to understand because several people were gathered around us, because others were talking loudly nearby, and because Mihad had begun to cry. Ali told me that he and his family had been trying to escape an area controlled by the RSF but had been caught in shelling at 2 a.m., the same explosions we had heard from our apartment in Omdur man. The children had been wounded by shrapnel. He had nowhere else to take them except this noisy ward, and no plans except to remain at the hospital and wait to see what would happen next.

Like a tsunami, the war has created wide swaths of physical wreckage. Farther out of town, at the Al-Jaili oil refinery, formerly the largest and most modern in the country—the focus of major Chinese investment—fires had burned so fiercely and for so long that giant pipelines and towering storage tanks, blackened by the inferno, lay mangled and twisted on the ground. At the studios of the Sudanese national broadcaster, the burned skeleton of what had been a television van, its satel lite dish still on top, stood in a garage near an accounting office that had been used as a prison. Graffiti was scrawled on the wall of the office, the lyrics to a song; clothes, office supplies, and rubble lay strewn across the floor. We walked through radio studios, dusty and abandoned, the presenters’ chairs covered in debris. In the television studios, recently refurbished with American assistance, old tapes belonging to the Sudanese national video archive had been used to build barricades.

Statistics are sometimes used to express the scale of the destruction in Sudan. About 14 million people have been displaced by years of fighting, more than in Ukraine and Gaza combined. Some 4 mil lion of them have fled across borders, many to arid, impoverished places—Chad, Ethiopia, South Sudan—where there are few resources to support them. At least 150,000 people have died in the conflict, but that’s likely a significant undercounting. Half the population, nearly 25 million people, is expected to go hungry this year. Hundreds of thousands of people are directly threat ened with starvation. More than 17 million children, out of 19 million, are not in school. A cholera epidemic rages. Malaria is endemic.

But no statistics can express the sense of pointlessness, of meaninglessness, that the war has left behind alongside the physical destruction. I felt this most strongly in the al-Ahamdda displaced-persons camp just outside Khartoum—although the word camp is misleading, giving a false impres sion of something organized, with a field kitchen and proper tents. None of those things was available at what was in fact a former school. Some 2,000 people were sleeping on the ground beneath makeshift shelters, or inside plain concrete rooms, using whatever blankets they had brought from wherever they used to call home. A young woman in a black headscarf told me she had just sat for her university exams when the civil war began but had already “forgot about education.” An older woman with a baby told me her husband had dis appeared three or four months earlier, but she didn’t know where or why. No international charities or agencies were anywhere in evidence. Only a few local volunteers from the Emergency Response Rooms, Sudan’s mutual-aid movement, were there to organize a daily meal for people who seemed to have washed up by accident and found they couldn’t leave.

As we were speaking with the volunteers, several boys ostentatiously carrying rifles stood guard a short distance away. One younger boy, dressed in a camouflage T-shirt and sandals—he told me he was 14 but seemed closer to 10—hung around watching the older boys. When one of them gave him a rifle to carry, just for a few minutes, he stood up straighter and solemnly posed for a photograph. He had surely seen people with guns, understood that those people had power, and wanted to be one of them.

What was the alternative? There was no school at the camp, and no work. There was nothing to do in the 100-degree heat except wait. The artillery fire, the burned television station, the melted refinery, the rapes and the murders, the children in the hospital—all of that had led to noth ing, built nothing, only this vacuum. Nointernational laws, no international organizations, no diplomats, and certainly no Americans are coming to fill it.

The end of the liberal world order is a phrase that gets thrown around a lot in conference rooms and university lecture halls in places like Washington and Brussels. But in al-Ahamdda, this theoretical idea has become reality. The liberal world order has already ended in Sudan, and there isn’t anything to replace it.

These are my photographs from the al-Ahamdda camp

The Emergency Response Rooms

In the last part of the article, I write about the civilian volunteers who have spent the past three years helping people survive, building a movement known as the Emergency Response Rooms. The volunteers talk about democracy and human rights, not because they have been influenced by outsiders but because they have seen what the world looks like without these things. As one of them told me: in the midst of destruction, the only possible response is to build:

Asked about motivations, one used the term nafeer, which refers to “communal labor” or “communal work.” Another mentioned takiya, when “people collect their food together and to eat together, to share it, if somebody doesn’t have food for sup- per or dinner.” While traveling in Sudan during Ramadan, I saw many instances of men far from home—drivers, workers, or indeed our translators—joining the communal prayers and meals served on the street when the fast is broken at sundown.

It’s easy, from a great distance, to be cynical about or dismissive of the prospects for good government in Sudan, but these are the same kinds of traditions that have become the foundation for more democratic, less violent political systems in other places. Nafeer reminded me of toloka, an old Slavic word I heard used to explain the roots of the volunteer movement in Ukraine. Takiya sounds like the community barn raisings of 19th-century rural America. The communal activists who draw on these old ideas do so not because of a foreign influence campaign, or because they have read John Locke or James Madison…They do so because their experience with autocracy, violence, and nihilism pushes them to want democracy, civilian government, and a system of power-sharing that would include all the people and all the tribes of Sudan.

These are people waiting in line for bean soup at one of the ERRs (my photographs). It costs a few cents a day to feed people in this manner. But some of the kitchens have had to serve fewer people, or on fewer days, because of USAID cuts.

If you want to help, this organization funds the ERRs directly: Mutual Aid Sudan

Autocracy Inc, paperback edition

coming in the US in three weeks, with a new introduction