Retired Colombian soldiers have been brought to Sudan to bolster the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), with promises of a good salary and tricked into thinking they would be providing security to oil drilling sites.

“Call that story ‘they escaped from hell’,” says a retired Colombian soldier over a shaky video call. He’s talking to a fellow veteran – someone he fought alongside for four months in Sudan’s civil war. Both had signed up as mercenaries. He’s only been back a month.

The two ex-soldiers were part of a battalion of mercenaries called the Desert Wolves – a codename for four companies made up solely of retired Colombian military personnel.

READ MORE: In-depth report on the Sudan crisis

They were brought to Sudan to bolster the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), a paramilitary group that launched a coup attempt in 2023 against Sudan’s military government, led by Abdel Fattah al-Burhan.

Some 24.6 million people in Sudan are now facing acute hunger. Another 12 million have been forced to flee – the largest displacement crisis in the world.

RSF reinforced with Colombian fighters

The RSF, the faction now reinforced with Colombian fighters, stands accused of some of the war’s worst atrocities – including blocking humanitarian aid. As La Silla Vacía has reported, nearly 300 ex-Colombian soldiers have joined the group since last year, many of them tricked into going.

They made their way through a transnational mercenary network headed by Álvaro Quijano, a retired colonel from the Colombian army. He runs the operation in partnership with Global Security Service Group, a private security firm based in the United Arab Emirates.

Sitting in a Bogotá bakery with a mug of hot chocolate, one of the men who recently came back from Sudan remembers how it all began. “I got there with about 120 or 150 others. We were a full company, the first one. We landed in late 2024,” he says.

READ MORE Sudan army says it has retaken presidential palace from RSF

That man, who asked to be called Héctor – not his real name – fears he could be killed if his identity is revealed. He is one of four returning mercenaries who spoke to La Silla Vacía. Together, they provided a detailed picture of what the Colombians were doing in the war.

By Héctor’s estimate, around 80 of his fellow fighters have since returned. But two more full companies have arrived since December. He reckons between 350 and 380 Colombian ex-soldiers are currently fighting in Sudan.

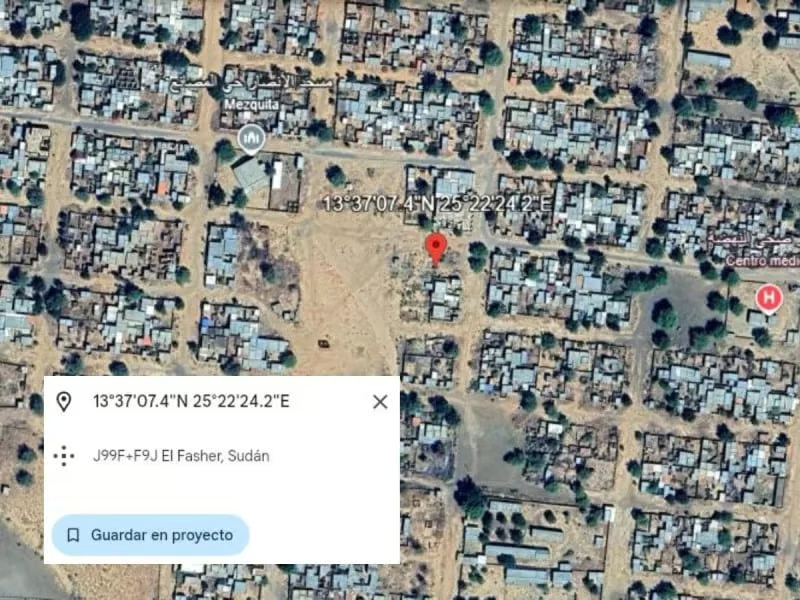

La Silla Vacía also obtained classified documents, war footage and geolocated images showing just how involved the Colombians have been – especially in one of the bloodiest parts of the conflict: the battle for El Fasher, a city in North Darfur. The United Nations has issued a resolution demanding that the RSF stop laying siege to it.

From oil security to ‘Call of Duty’ in El Fasher

An 18-page document containing the secret orders for the Colombian mercenary battalion deployed in Sudan to El Fasher includes instructions aimed at preventing violations of human rights and international humanitarian law.

These orders are hard to square with the actions of the RSF, the armed group the Colombians are fighting alongside, who have been accused of war crimes. The document also outlines procedures for what to do during a sandstorm or an airstrike by the Sudanese army.

The first company of Colombians reached El Fasher in November 2024. “The fighting there was street to street. You ever played Call of Duty? Just like that,” says Héctor.

READ MORE Kenya’s legacy and its relationship with Sudan’s RSF: All the light we cannot see

He was among the first wave of retired Colombian soldiers to sign up. He signed a non-disclosure agreement with Global Security Service Group, a UAE-based firm certified by the Emirati state. The contract he was offered promised static security work at oil facilities in the Middle East or Africa.

But the route led him instead to Sudan. His passport shows he flew from Abu Dhabi to Benghazi in northern Libya. There, men he identified as Libyan soldiers took all their passports. “They told us no one was leaving Libya. They said the only way back was to finish the journey all the way to the RSF.”

They were kept in barracks for several weeks. Then part of the group was packed into a convoy of pickup trucks and driven across the Sahara – north to south – until they reached the Sudanese border. To avoid ambushes, they skirted the frontier between Chad and Sudan.

Duped in Libya

“From Libya to Chad, we were handed over to a sort of pirate crew,” says Héctor. “By then we were armed. Somewhere on the border between Libya, Chad and Sudan, we got ambushed. The pirates knew the drill. They just yelled, ‘Move it, move it. Enemy!’”

As night fell, six pickup trucks with their headlights off came flying over the dunes. Each had a .50-calibre machine gun mounted in the back. In the chaos, one vehicle crashed into another. Corporal (ret.) Christian Lombana’s leg was crushed in the accident.

READ MORE Sudan takes UAE to court over genocide complicity

Lombana left behind his identity card, passport and even his Bogotá bus pass. A militia allied to the Sudanese government found them and posted them online – hard proof of Colombian involvement. According to witnesses, Lombana was later flown to the UAE, where he underwent several surgeries to save his leg.

The four Colombian fighters believe they were sold out. They suspect Libyan officials leaked their location to pro-government Sudanese militias, after tensions flared in Benghazi. After regrouping on the Chadian border, they received new orders from Colonel Quijano, the man running the operation from Dubai: proceed to meet up with the RSF.

I went because I wanted to improve my life.

The offer was $2,600 a month

“We’d just crossed into Sudan and made it about 600 metres when more than 40 trucks rolled up, all with .50 cals. We asked the driver, ‘Enemy? Enemy?’ But they were RSF, so they flagged us down. We got out, handed things over, and from there, on to El Fasher.”

The full first company reached the outskirts of El Fasher in late 2024. Other Colombian platoons were already there. The first to arrive had been drone operators. Among them were the first confirmed Colombian casualties – three men killed by a bomb. Their bodies have not been returned.

READ MORE Sudan: Fighting in El Fasher shuts last hospital in Darfur city

The Sudanese army also claimed to have killed more Colombians on 29 November 2024. “Four Emiratis and 22 Colombian mercenaries were killed by suicide drones,” says a military communiqué. No bodies were handed over.

The Colombians say this is false. According to their sources, the men killed were Russian mercenaries, likely from Wagner (now Africa Corps) – the Kremlin-linked outfit known to be operating in Sudan since 2023.

Tayra and drone strikes

Héctor says only three Colombians have died so far, all in October. But many more have been wounded – by drone strikes, in firefights, or by shrapnel from bombs dropped by Sudanese fighter jets. The soldiers call the jets tayra, an Arabic slang for plane.

“At dawn, the lookout would shout, ‘Tayra! Tayra!’ And we’d all dive into the trenches. You’d hear the bombs whistling down. They could land six kilometres away, but even in the trench, you felt the ground shake,” says Héctor.

The Desert Wolves’ orders include procedures for air attacks and drone strikes. “In the event of a kamikaze drone attack,” says the document, “follow the same procedure as for an attack by a manned aircraft [‘Tayra’]. On command, respond with rifle fire.”

READ MORE Iran’s rising influence and Sudan’s drone gambit

While Colonel (ret.) Quijano runs the show from Dubai, command on the ground falls to two other retired Colombian officers. The battalion commander is Iván Darío Castillo Rodríguez. His deputy is John Jairo Mondol Duque, who arrived with Héctor and led operations in El Fasher.

Evidence of their presence includes a video showing a mortar strike carried out by Colombians, with geotagged coordinates. A search of those coordinates in Google Maps places the strike inside El Fasher. The video is dated January 2025.

The footage matches a point on Google Earth – squarely in the centre of El Fasher. “We pushed them back with mortars, drones and plenty of snipers. We’ve taken out a lot of Sudanese troops,” says one ex-soldier, trained in elite units back in Colombia.

RSF child soldiers

There are no field medics so the Colombians have had to patch up wounded RSF fighters themselves – many of them children. “They had 10- and 11-year-olds fighting,” says Héctor, showing a video of a Sudanese boy injured by a kamikaze drone.

But Héctor and the three others who spoke to La Silla Vacía say they all asked to be sent home soon after arriving. The war was not what they were promised, and neither were the perks. A4SI – another firm involved – never paid out life insurance policies or the promised $5,000 bonuses every two months, intended to keep them quiet and fighting.

Many, like Héctor, have demanded to leave. He estimates that around 80 have made it out. But replacements keep arriving. Since La Silla Vacía exposed the operation, A4SI and GSSG have rerouted their transfers in and out of Sudan.

Nyala: Colombia mercenary hub

Nyala, the capital of South Darfur, is the RSF’s rear base and launchpad for its campaign in El Fasher. Last month, the Reuters news agency published satellite images from Maxar, an intelligence firm, showing that between January and February this year, the RSF built three hangars along Nyala’s runway. Large reconnaissance drones have also been spotted at the site.

The city has become the main hub for Colombian mercenaries. It serves as the rallying point for the Desert Wolves battalion – both for those arriving and for those trying to leave, often wounded or disillusioned. According to returning ex-soldiers, two full companies – around 300 men – have reached Nyala since late last year.

“Before the media storm in December, the company used a route through Libya to get into Sudan,” says one of the fighters who made it back. “But after the whole thing collapsed, they switched to a new route.”

That route, according to his account, begins in Madrid. From there, they fly to Ethiopia. Then on to Bosaso, a key port in Somalia, before boarding a plane to N’Djamena, the capital of Chad. The final leg ends in Nyala, where the RSF controls the airport.

“We flew into Nyala from Chad,” the Colombian told La Silla Vacía. “The flight from N’Djamena to Sudan takes about two hours. We landed already armed – drones, RPGs, missiles, the works.”

Once there, the Colombians train RSF fighters, many of whom operate with little discipline or structure.

Héctor and other members of his unit, who had asked to return home, also passed through Nyala on the way out. “We were on the outskirts of El Fasher. It’s about three hours to Nyala. But to stay safe, we took a long detour – it took us nine hours. You never know if the Sudanese army will ambush you,” he says.

If we’re in Bosaso, why a UAE stamp?

Once in Nyala, they handed over their weapons and boarded a plane for the return journey. His passport bears two key stamps, both pointing again to the influence of the United Arab Emirates. One is from the UAE. The other, from Somalia, marks his exit through the port of Bosaso, at the northwestern tip of the country.

The UAE has tightened its grip in Bosaso in recent years, investing heavily in port infrastructure. It has also provided military support to Somalia – to such a degree that returning Colombians say they passed through an Emirati base.

“In Bosaso, it’s easier to move into Chad,” says one of the mercenaries. “The UAE has a military base there, and they’ve got a deal to use it.”

Misled ex-soldiers

“I went because I wanted to improve my life,” says Héctor. “The offer was $2,600 a month – around 10m Colombian pesos. But once you’re in, they send you into combat. I was tricked into going to the war that’s happening right now in Sudan.”

He knows that back in Colombia, finding any job that pays that much will be difficult.

So why do Colombian ex-soldiers keep going, even though they know they’re signing up for a brutal civil war on the RSF’s side? The answer, from everyone interviewed, is the same: they go to earn better money – and they are misled.

“Maybe it’s just because of how hard things are in our country,” says one. Another says: “When I got to Sudan the first time, a colonel told me not to believe what the news says.”

A third ex-soldier says: “They are still being lied to. They are told they will be instructors. Instructors? In the middle of a f***ing war?”

What draws many of these retired Colombian soldiers is the pay. Contracts typically offer $2,600 for privates and $3,400 for sergeants. But many report being underpaid or not paid at all.

Under Colombia’s special military rules, most professional soldiers retire around the age of 40. Others leave earlier if they fail to rise through the ranks. Most do not receive a pension that matches what they can earn abroad.

President Petro condemns mercenarism

Thanks to Colombia’s long-running internal conflict, they are often well-trained and battle-hardened – qualities that make them attractive to private military firms, especially in war zones like Ukraine.

“Mercenarism must be banned,” said President Gustavo Petro in November 2024, after the first investigation into Colombian fighters in Sudan. He instructed the foreign ministry to find a way to bring those men back from Africa. But since then, the flow has not stopped, nor have the remains of the three Colombians killed in October been repatriated.

READ MORE Investment in distrust: Is the UK ministerial meeting on Sudan doomed?

When the scandal broke last year, then-foreign minister Luis Gilberto Murillo was preparing to visit Egypt – an ally of Sudan’s official government. Government sources, speaking off the record, said there were diplomatic efforts to recover the bodies of the dead. None succeeded.

Meanwhile, with the number of Colombian mercenaries in Ukraine also rising, Murillo introduced a bill to outlaw mercenarism in Colombia. The aim is to give authorities the legal tools to stop the outflow of ex-soldiers, who are no longer under military discipline. The bill is now in its second reading in the Senate.

For now, international agencies and NGOs following the conflict in Sudan are warning that the war is likely to escalate. And the Colombian mercenary operation shows no sign of slowing down.

This story was first reported by the Colombian news site La Silla Vacía, republished here with permission.