Source: Africa File

Michael DeAngelo, Liam Karr, Yale Ford, Anahita Asudani and Alexis Thomas

To receive the weekly Africa File or triweekly Congo War Security Review via email, please subscribe here. Follow CTP on X, LinkedIn, and BlueSky.

Key Takeaways:

Ethiopia. The Ethiopian federal government has begun a military buildup near Tigray region in the aftermath of recent clashes, indicating preparations for an expanded and prolonged war in northern Ethiopia that would involve Eritrea. A war in Tigray would likely become another arena in the regional proxy war in the Red Sea involving Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates.

Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). A US-linked private military company (PMC) is reportedly supporting an ongoing Congolese army offensive against militias aligned with Rwandan-backed M23 rebels in the South Kivu highlands in the eastern DRC. The deployment of contractors from Vectus Global—a PMC linked to American citizen Erik Prince—to the front line is a notable expansion of US involvement in the conflict and is part of growing cooperation between the PMC and the Congolese government since late 2024.

South Sudan. The South Sudanese federal government and leading opposition faction are on the verge of sparking a renewed civil war amid recent large-scale battles. The ongoing trial of opposition leader First Vice President Reik Machar could escalate the battles into a civil war, which would have a devastating humanitarian impact and allow the warring parties in neighboring Sudan’s civil war to exploit the instability.

Nigeria. The US military will deploy 200 troops to Nigeria in the coming weeks in the latest step in growing counterterrorism cooperation between the US and Nigeria, which is responding to one of the deadliest Salafi-jihadist attacks in years.

Figure 1. Africa File, February 12, 2026

Source: Liam Karr.

Assessments:

Ethiopia

Authors: Michael DeAngelo, Liam Karr, and Anahita Asudani

The Ethiopian federal government has begun a military buildup near Tigray region in the aftermath of recent clashes, indicating preparations for an expanded and prolonged war in northern Ethiopia. Anti-federal government outlet Amhara War Updates and an independent journalist have reported that the Ethiopian National Defense Force (ENDF) is redeploying a large number of forces from the Amhara and Oromia regions toward Tigray since February 7.[1] The Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) also accused the ENDF of military preparations and operations in Tigray on February 9.[2]

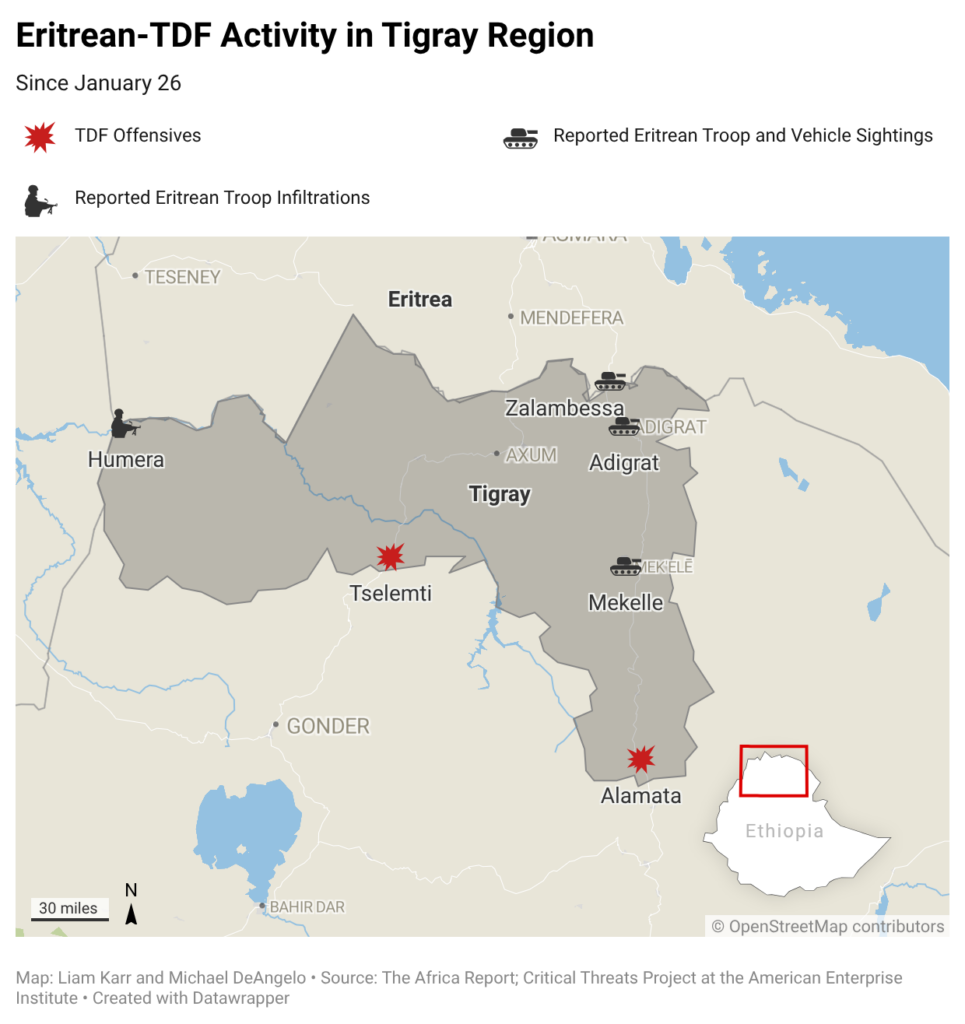

The troop movements come after the Tigray Defense Forces (TDF)—the TPLF’s military force—launched offensives against the ENDF and allied Amhara militia fighters in northwestern and southern Tigray in late January, marking the first large-scale hostilities between the federal government and TPLF since the end of the Tigray war in 2022.[3] The TDF pushed the ENDF and its militia allies out of disputed territory near the Amhara border before withdrawing from these seized areas in northwestern Tigray.[4] TDF and TIA head Tadesse Worede cited the federal government’s “failure” to implement the 2022 Pretoria peace agreement that ended the Tigray war—particularly the continued displacement of Tigrayans and presence of Amhara forces in the disputed areas—as the reason for the offensives.[5] Worede did state that large-scale clashes “should not have happened” and that the TIA wants to avoid war, however, amid other efforts from the TPLF to de-escalate the situation.[6]

Eritrea is almost certainly already providing support to the TPLF and would be involved in a wider war in Tigray. Eritrea has formed an alliance of convenience with the TPLF since early 2025 despite their historic animosity. Eritrea and Ethiopia put aside their decades-long rivalry and fought on the same side against the TPLF in the Tigray war. The Pretoria peace process excluded Eritrea, however, and Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed has since made several thinly veiled threats to annex Eritrea’s port of Assab.[7] Eritrean President Isaias Afwerki promised to protect the TPLF in the event of a conflict with Ethiopia in early 2025 during one of several high-level meetings between Eritrean and TPLF officials, according to French outlet Africa Intelligence.[8] Eritrea reportedly may have provided intelligence support for the TPLF’s de facto coup against the TIA in March 2025 and the TDF’s recent offensives in northwestern and southern Tigray.[9] An Ethiopian military official told The Africa Report on February 11 that Eritrean forces have infiltrated Tigray and established positions along key roads.[10] The TPLF has previously confirmed its desire to bolster ties with Eritrea and left open the possibility of an alliance in a conflict against Ethiopia but denied ongoing military coordination.[11]

Figure 2. Eritrean-TDF Activity in Tigray

Source: Liam Karr; Michael DeAngelo; The Africa Report.

Ethiopia is likely preparing for war with Eritrea as part of the standoff in Tigray. Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed publicly denounced Eritrean forces that perpetuated mass killings in Tigray during the Tigray war on February 3, and said that these atrocities strained Eritrea-Ethiopia relations, not Ethiopia’s desire to obtain sea access through Eritrea.[12] Eritrean Minister of Information Yemane Gebremeskal stated that Abiy’s statements represent Ethiopia’s “reckless and illicit war agenda against Eritrea.”[13] Ethiopian Foreign Minister Gedion Timothewos then sent a letter to his Eritrean counterpart on February 7, accusing Eritrea of coordinating with the TPLF and demanding that Eritrean forces still present in Tigray withdraw.[14] Timothewos also conditioned “negotiations for a comprehensive settlement” on Ethiopian access to Eritrea’s port of Assab on Eritrea halting activities in Tigray.[15] Eritrea’s Ministry of Information called the allegations “astounding” and “false.”[16]

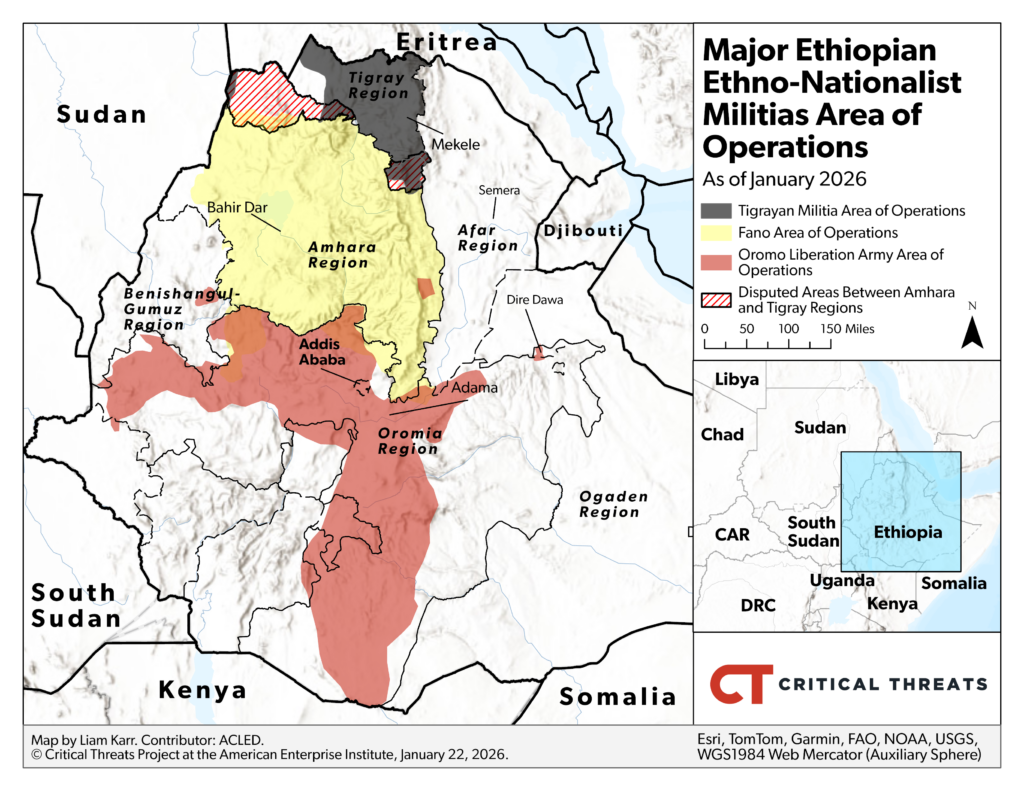

Anti-Ethiopian federal government Amhara ethno-nationalist Fano militias have taken advantage of troop redeployments from Amhara to Tigray, which could constrain the Ethiopian federal government from initiating a war in Tigray. Fano has launched offensives in central and western Amhara and captured several towns along key roads, including Debre-Tabor, which is located on the main B22 highway connecting eastern and western Amhara.[17]

Some Fano forces may be at least loosely coordinating with Eritrea and the TPLF. Amhara War Updates reported that Fano has attacked ENDF units that may be redeploying toward Tigray.[18] Eritrea has preexisting ties with Fano, having trained Fano forces for several years.[19] The Ethiopian federal government and Amhara regional government have accused Eritrea of supplying Fano in recent months.[20] The Economist reported in November that Eritrean, Fano, and TPLF officials had met to discuss military coordination.[21]

Figure 3. Ethno-Nationalist Militias Area of Operation in Northern Ethiopia

Source: Liam Karr; Armed Conflict Location & Event Data.

A war in Tigray would likely join Sudan as another arena in the emerging regional proxy war in the Red Sea. The UAE has a strategic partnership with Ethiopia and views it as a regional linchpin, investing billions in Ethiopia’s economy and supplying advanced military equipment.[22] The UAE’s provision of drones and a supply air bridge during the Tigray war was essential in the Ethiopian federal government halting a TPLF advance on Addis Ababa—the Ethiopian capital—and forcing the TPLF into peace talks.[23] Egypt views Ethiopia as a threat to its influence in the Nile River Basin and Red Sea and has cultivated strong ties with Eritrea, including a high-level security dialogue and a recent investment deal in Eritrea’s port of Assab that allegedly grants Egypt naval access.[24] Saudi Arabia has grown diplomatic ties with Eritrea over the last several years and considered investing in Assab as part of efforts to counter Emirati influence in the region, and Egypt has sought to facilitate even closer ties between its Eritrean and Saudi allies in 2026.[25] These same external factions are increasing their support for opposing factions in neighboring Sudan, where the UAE and Ethiopia back the Rapid Support Forces, and Egypt, Eritrea, and Saudi Arabia back the Sudanese Armed Forces.[26] Saudi Arabia also has strong economic ties with Ethiopia, however, and Saudi delegations have likely attempted to mediate in recent meetings with Ethiopian and Eritrean officials to discuss regional stability.[27]

Democratic Republic of the Congo

Author: Yale Ford

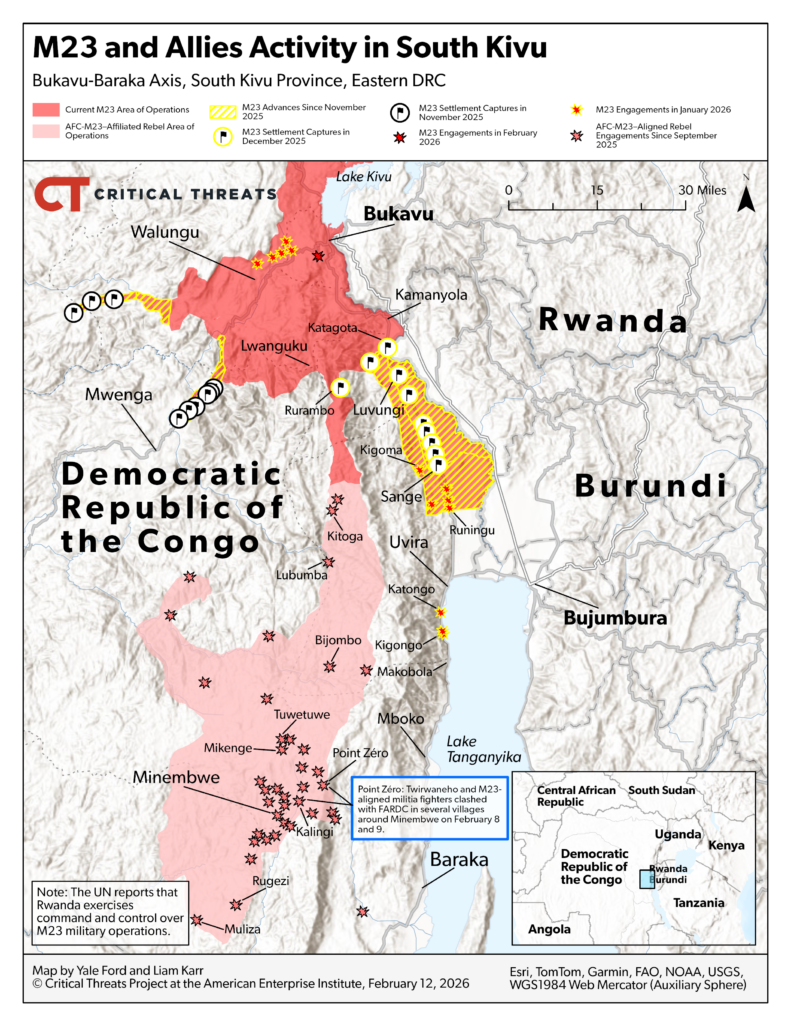

A US-linked private military company (PMC) is reportedly supporting an ongoing Congolese army (FARDC) offensive in the South Kivu highlands against Rwandan-backed M23-linked militias in the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Reuters cited several insider sources on February 10 who confirmed that Erik Prince, a US private security contractor and informal adviser of US President Donald Trump, sent forces from Prince’s PMC, Vectus Global, to South Kivu province to assist the FARDC in securing Uvira town after M23 forces withdrew under US diplomatic pressure in mid-January.[28] The report said that Prince has deployed contractors and drone operators to Uvira and the highlands at the Congolese government’s request.[29] The Reuters report follows a recent investigation by the French investigative outlet Africa Intelligence that reported that Vectus Global assisted FARDC artillery units and provided intelligence support in securing Uvira.[30]

Prince’s team and Israeli advisers are reportedly supporting FARDC special forces that are fighting M23-aligned rebel militia groups in the highlands as part of a new offensive since the FARDC took back Uvira.[31] The FARDC launched an operation in this mountainous area in late January and has intensified ground and air attacks to recapture several areas around Minembwe town in Fizi district, which is a stronghold for M23-aligned militia groups.[32] The highlands around Minembwe control access on several axes to key towns in the lowlands along Lake Tanganyika and potential lines of advance toward the DRC’s economic engine in the southern DRC. Vectus Global-backed FARDC special forces are using attack drones, and locals have found damaged high-tech mortar shell drop systems amid the fighting.[33] M23 claimed that the FARDC conducted more than 70 air and drone strikes on its positions and noncombatants in the highlands between January 22 and February 1.[34] The latest reports indicate that the FARDC has taken control of numerous villages around Minembwe since early February, including at least four contested villages close to the town on February 11.[35] The heavy fighting in the highlands has reportedly caused a significant displacement of people in recent weeks.[36]

Figure 4. M23 and Allies Activity in South Kivu

Source: Yale Ford, Liam Karr, and Claire Schreder.

Vectus Global’s engagement in the eastern DRC is part of growing cooperation between the PMC and the Congolese government since 2024. The Congolese government has partnered with Vectus Global since October 2024, mainly to help crack down on tax evasion in the DRC’s mining sector. This deployment directly to the front line expands Prince’s—and the United States’—involvement in the conflict, however. Prince’s deployment to the DRC is not officially sanctioned by the US government, but a senior Congolese security official told Reuters that the deployment to South Kivu is “in line with the [US-DRC] minerals-for-security deal.”[37] Reuters reported that Prince’s team could remain closely involved in the conflict, and the Congolese security official said that the presence of contractors linked to the United States via Prince aims to serve as a “deterrent” to M23 troops, who may be reluctant to risk a direct confrontation with American personnel.[38]

South Sudan

Author: Michael DeAngelo

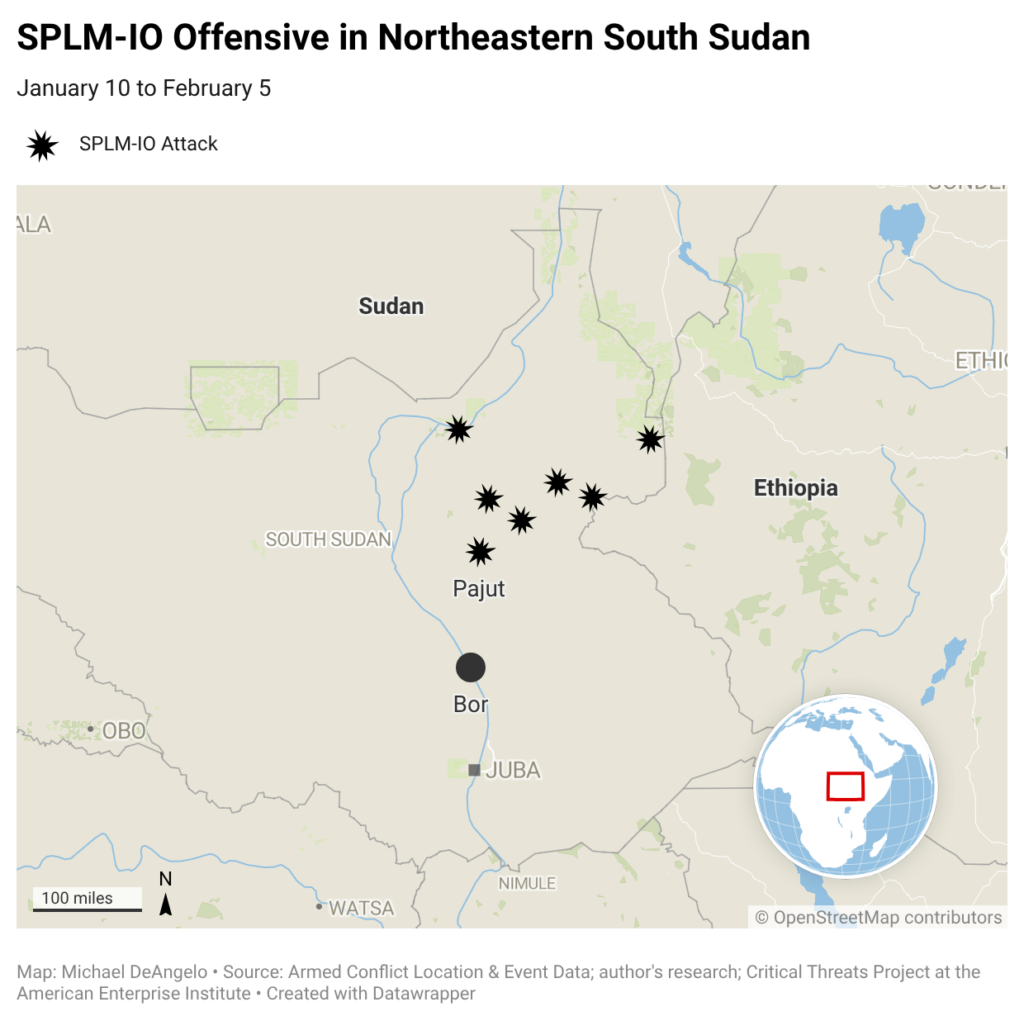

The South Sudanese military and leading opposition faction have engaged in large-scale battles in recent weeks, putting the country on the path to a renewed civil war. South Sudanese Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-in-Opposition (SPLM-IO) rebels launched an offensive in northeastern South Sudan in December 2025. The SPLM-IO concentrated its offensive in the Jonglei, Unity, and Upper Nile states, capturing South Sudanese military—known as the South Sudan People’s Defense Forces (SSPDF)—bases and multiple county capitals.[39] The SPLM-IO seized Pajut on January 16, which is a key town located approximately 120 miles north of Bor, the Jonglei state capital.[40] The SPLM-IO spokesperson announced on January 19 that SPLM-IO would advance toward Juba—the South Sudanese capital located approximately 125 miles south of Bor—to overthrow the federal government.[41] SPLM-IO and the allied Nuer White Army militia announced the deployment of 10,000 additional fighters to the “designated war front” in Jonglei on January 23, although the SPLM-IO later characterized the mobilization as defensive.[42]

Figure 5. SPLM-IO Offensive in Northeastern South Sudan

Source: Michael DeAngelo; Armed Conflict Location & Event Data; author’s research.

The SSPDF has responded with a counteroffensive in northeastern South Sudan. SSPDF chief Paul Nang Majok told SSPDF troops on January 23 that they had seven days to “crush the rebellion” in northeastern South Sudan.[43] The SSPDF has deployed large reinforcements to Jonglei and retaken some positions, although operations are ongoing.[44] The SSPDF has conducted airstrikes on SPLM-IO positions, clashed with the SPLM-IO in Pajut, and retaken Yuai, the Uror county capital.[45]

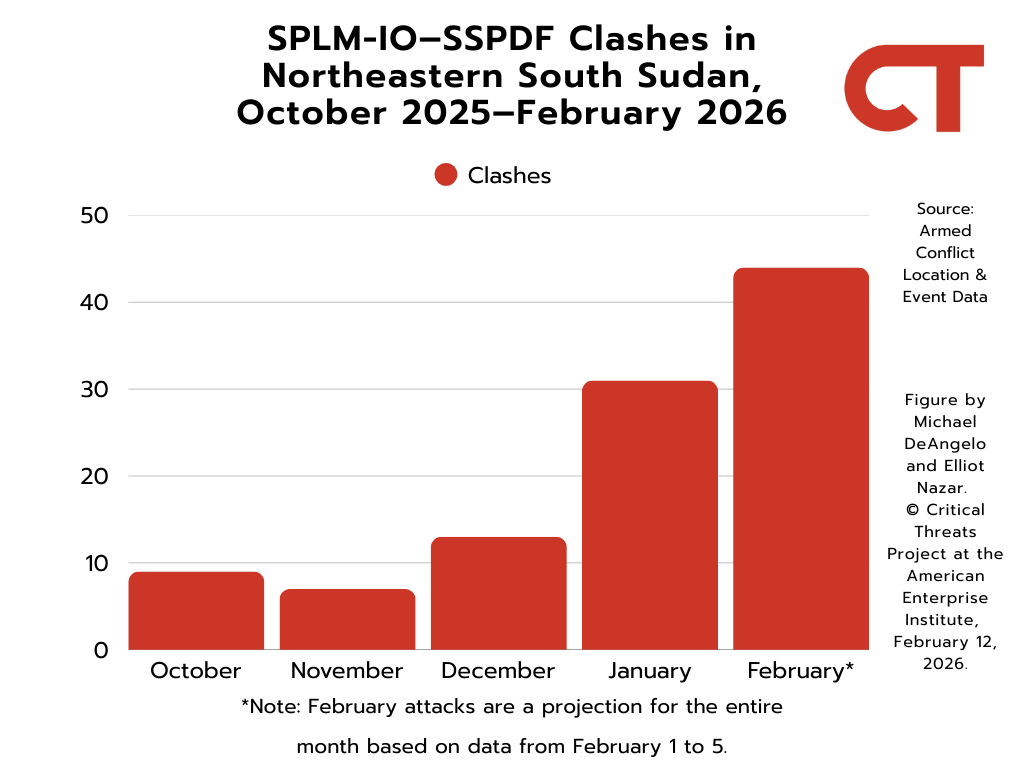

Figure 6. SPLM-IO and SSPDF Clashes in Northeastern South Sudan

Source: Michael DeAngelo; Elliot Nazar; Armed Conflict Location & Event Data.

The conflict is the result of the collapse of the power-sharing deal that ended the ethnically based civil war between President Salva Kiir and First Vice President Reik Machar in 2018. Kiir’s and Machar’s factions waged a civil war against each other over control of the government and state resources from 2013 to 2018.[46] The civil war began in the months after Kiir accused Machar of plotting a coup and fired him as first vice president.[47] The civil war was largely split along ethnic lines, as Kiir represents Dinka and Machar represents Nuer, which are the largest and second-largest ethnic groups in South Sudan.[48] Kiir and Machar eventually signed a peace agreement and formed a unity government in 2020.[49] The government has not implemented key provisions of the peace agreement, however, as distrust between the factions has disrupted the drafting of a permanent constitution, planned elections and the integration of armed factions into the Dinka-led South Sudanese security forces.[50] Kiir postponed planned 2024 elections to December 2026, citing a lack of readiness partially due to the stalled drafting of a permanent constitution.[51]

Clashes broke out across South Sudan in early 2025 amid the lingering tensions. The most significant fighting occurred in Upper Nile state in March 2025, when the Nuer White Army captured the SSPDF’s base in Nasir, killing a South Sudanese general.[52] The SSPDF launched a series of airstrikes in Nasir and surrounding areas and recaptured the town in April.[53] The federal government placed Machar under house arrest over suspicion that he directed the Nasir attack.[54] The federal government also arrested several Machar allies and has since dismissed others from key government posts, including positions that the power-sharing agreement granted SPLM-IO.[55] International observers have warned that the ongoing political disputes and stalled implementation of the peace agreement threaten to spark a civil war.[56]

The trial of Machar stemming from the White Army’s offensive is contributing to the ongoing hostilities, which likely intensify if the justice system convicts Machar. South Sudan’s Ministry of Justice charged Machar and several high-profile associates with crimes against humanity, murder, and treason on September 11, charges that are punishable by death.[57] Kiir subsequently suspended Machar as first vice president and allowed for the establishment of a special court over Machar’s objections.[58] The defense has tried to delay the proceedings multiple times, questioning their legality and objectivity.[59] The trial is currently hearing expert testimony, and there is no timeline on a potential end.[60] Multiple opposition factions have coalesced around the SPLM-IO and pledged to fight against the federal government, and clashes between SPLM-IO-aligned forces and the SSPDF increased over three-fold from October to January in northeastern Sudan.[61]

A civil war would likely have a devastating humanitarian impact on South Sudanese civilians and Sudanese refugees who have fled the war in Sudan. The United Nations (UN) reported that the recent battles in Jonglei have already displaced nearly 300,000 people.[62] The UN also reported that 450,000 children are at risk of acute malnutrition in Jonglei.[63] The UN and several aid organizations have criticized the federal government for restricting humanitarian access in Jonglei.[64] The World Food Programme also halted operations in a county in Upper Nile state on February 4 after militants attacked one of its convoys.[65] The presence of over one million people who fled Sudan to South Sudan as a result of Sudan’s civil war had already strained humanitarian resources.[66]

A civil war would very likely include both ethnic targeting and indiscriminate violence against civilians. A South Sudanese general leading troops in northeastern South Sudan directed his forces to not “spare an elderly . . . a chicken . . . a house and anything” in their ongoing counteroffensive in Nuer-dominated territory.[67] The civil war from 2013 to 2018 involved widespread ethnic targeting between Dinka and Nuer and their respective armed groups and indiscriminate mass killings and rape of civilians.[68] The civil war killed up to 400,000 people, with as many as half of whom died from nonviolent war-related causes such as disease and starvation.[69]

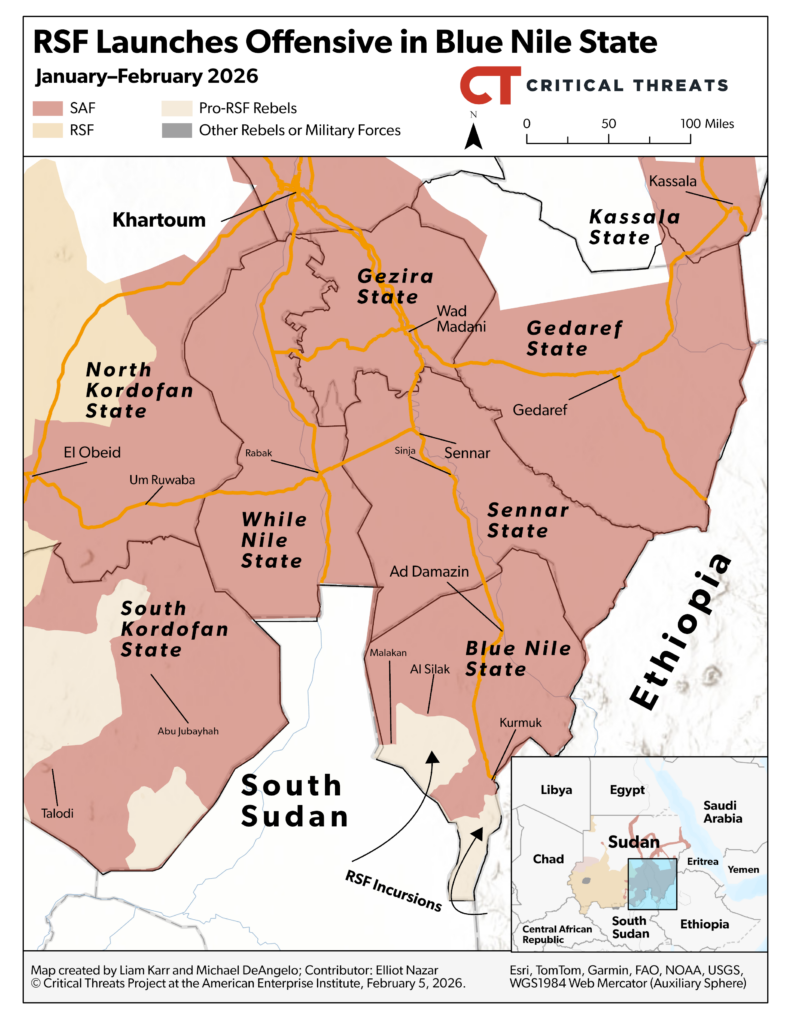

The Rapid Support Forces (RSF) and Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) could exploit a civil war in South Sudan to further their military aims in Sudan. The RSF has used South Sudan for basing and supply purposes, cultivating closer ties with Kiir’s administration as the Sudanese civil war has progressed. The RSF and allied Sudan People’s Liberation Movement–North (SPLM-N) al Hilu militia, which is aligned with Kiir, use supply lines stretching into South Sudan.[70] The RSF has also reportedly established rear bases in South Sudan, from which the group attacked SPLM-IO fighters during the fighting in Upper Nile state in March 2025.[71] The RSF and South Sudan have further strengthened ties since the RSF’s capture of the Heglig oil fields—located in Sudan’s West Kordofan state on the border with South Sudan—in early December, collaborating to resume operations at the facilities despite scattered infighting.[72] RSF head Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo and top South Sudanese oil and security officials met in Nairobi in late January.[73] Sudan’s civil war has significantly reduced South Sudan’s oil export revenues, sending the federal government into a fiscal crisis.[74]

The SAF views the RSF’s presence in South Sudan as a threat on its eastern flank, straining relations with South Sudan and potentially causing the SAF to support the SPLM-IO. SAF officials have stated that RSF and SPLM-N al Hilu fighters have transited through South Sudan to launch attacks in southeastern Sudan, which the SAF now views as a second front in Sudan’s civil war, as part of a broader offensive since late January.[75] SAF officials previously accused South Sudan of allowing the RSF to transit through and recruit in South Sudan.[76] The International Crisis Group reported in March 2025 that the SAF may have leveraged its historic ties to SPLM-IO-aligned forces and sent supplies.[77] CTP has previously assessed that the RSF and SAF are likely backing opposing sides in South Sudan.[78]

Figure 7. RSF Launches Offensive in Blue Nile State

Source: Liam Karr; Michael DeAngelo; Elliot Nazar.

Nigeria

Authors: Alexis Thomas and Liam Karr

The US military will deploy 200 troops to Nigeria in the coming weeks in the latest step in growing counterterrorism cooperation between the US and Nigeria. The Wall Street Journal reported on February 10 that the United States is sending 200 troops to various parts of Nigeria in the coming weeks to train the Nigerian military.[79] A Nigerian military spokesperson told The Wall Street Journal that US troops would not be involved in combat and that Nigeria requested the assistance.[80] US Africa Command (AFRICOM) Commander General Dagvin Anderson said on February 3 that the United States had already dispatched a small team of military officers to Nigeria to support Nigerian counterterrorism efforts, particularly providing “unique capabilities” to support intelligence gathering efforts.[81] General Anderson met with Nigerian President Bola Tinubu and other top Nigerian security officials in Abuja on February 8.[82]

The US deployments are part of growing security cooperation between the United States and Nigeria since November 2025. The United States and Nigeria agreed in late November to deepen security cooperation and intelligence sharing and establish a US-Nigerian working group to address violence against Christians after a high-level meeting between Nigerian and US defense officials.[83] US and Nigerian officials met for the first session of the working group focused in Abuja on January 22.[84]

The growing cooperation has already led to increased US military activity in Nigeria since late November. AFRICOM drafted plans to target Salafi-jihadi groups in Nigeria in late 2025 at the behest of President Donald Trump, who promised action to protect Nigerian Christians from violence in October.[85] The United States resumed intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) operations over Nigeria in late November for the first time since 2024 and conducted missile strikes targeting IS-linked militants in northern Nigeria on December 25.[86] AFRICOM has reportedly continued daily ISR missions launched from Ghana.[87]

The deployment comes as the Nigerian military is intensifying counterterrorism operations in northwestern Nigeria in response to the largest Salafi-jihadist attack in the country in years. President Tinubu deployed an army battalion to Kaiama district in Kwara state on February 5 to launch Operation Savannah Shield. The offensive is in response to an attack by Boko Haram militants from the Sadiku faction that killed at least 170 civilians in Nuku and Woro villages in the area on February 3.[88] Nigerian forces had withdrawn from the area in November 2025, and locals had appealed for assistance after receiving threatening letters days before the attack. The militants had sent multiple “warning” letters and pamphlets to the towns over the past five months, including letters addressed from Boko Haram’s Lake Chad–based leader Bakura Doro, that urged the locals to accept their preachings.[89]

The Boko Haram militants are continuing their campaign in Kwara after the massacre. Likely Boko Haram fighters reportedly sent another threatening letter to the Dunshigogo community in Kaiama district the week after the February 3 massacre.[90] The letter had similar language to the threat Boko Haram sent to the Woro community, warning residents that the fighters would soon visit the area. Residents reportedly fled and closed businesses in response to the threat.[91]

Africa File Data Cutoff: February 12, 2026, at 10 a.m.

The Critical Threats Project’s Africa File provides regular analysis and assessments of major developments regarding state and nonstate actors’ activities in Africa that undermine regional stability and threaten US personnel and interests.