Source: African Arguments

Debating Ideas reflects the values and editorial ethos of the African Arguments book series, publishing engaged, often radical, scholarship, original and activist writing from within the African continent and beyond. It offers debates and engagements, contexts and controversies, and reviews and responses flowing from the African Arguments books. It is edited and managed by the International African Institute, hosted at SOAS University of London, the owners of the book series of the same name.

On March 26, 2025, the German Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office launched a large-scale operation (searches and arrests) among members of the Eritrean community residing in Germany. The individuals targeted are suspected of ‘forming and membership of a domestic terrorist organization (”Brigade N’Hamedu”).’ The Federal Prosecutor’s Office is referring to the Blue Revolution, a grassroots movement born simultaneously in various countries where the Eritrean diaspora is represented. It is led by young people who fled Eritrea, its one-party regime, the People’s Front for Democracy and Justice (PFDJ), and the atrocities committed by its arbitrary government.

Eritrea won de facto independence in 1991. The Eritrean People’s Liberation Front was at the forefront of the liberation struggle. Isayas Afewerki, Eritrea’s long serving President, gradually ousted the other leaders to create the PFDJ in 1994, which would become his personal tool of governance. The 1997 Constitution was intended to establish the rule of law, but war with Ethiopia broke out in 1998. Isayas took advantage of the situation to establish a totalitarian regime living in a permanent state of emergency. Eritrean society never disarmed, and open-ended compulsory military service was imposed that still enslaves all Eritrean citizens from the age of 16. With the economy nationalized, or rather hijacked for the benefit of party cadres, conscripts are exploited in a mafia-like system.

In 2001, 15 PFDJ leaders denounced this drift. Nicknamed the G-15, they were all arrested. The newspaper Setit, co-founded by the journalist Dawit Isaak, tried to report these facts. But on September 11, 2001, as the whole world had its eyes on New York, Isayas had all the newspapers shut down and the editorial staff of Setit arrested. Dawit Isaak is still a prisoner today, making him the world’s longest detained journalist. With all voices stifled within the country, the opposition is trying to organize abroad, but even in the Western metropoles they are harassed by PFDJ moles operating in diplomatic missions or in the form of ultra-violent militias.

Events in Giessen and Stuttgart

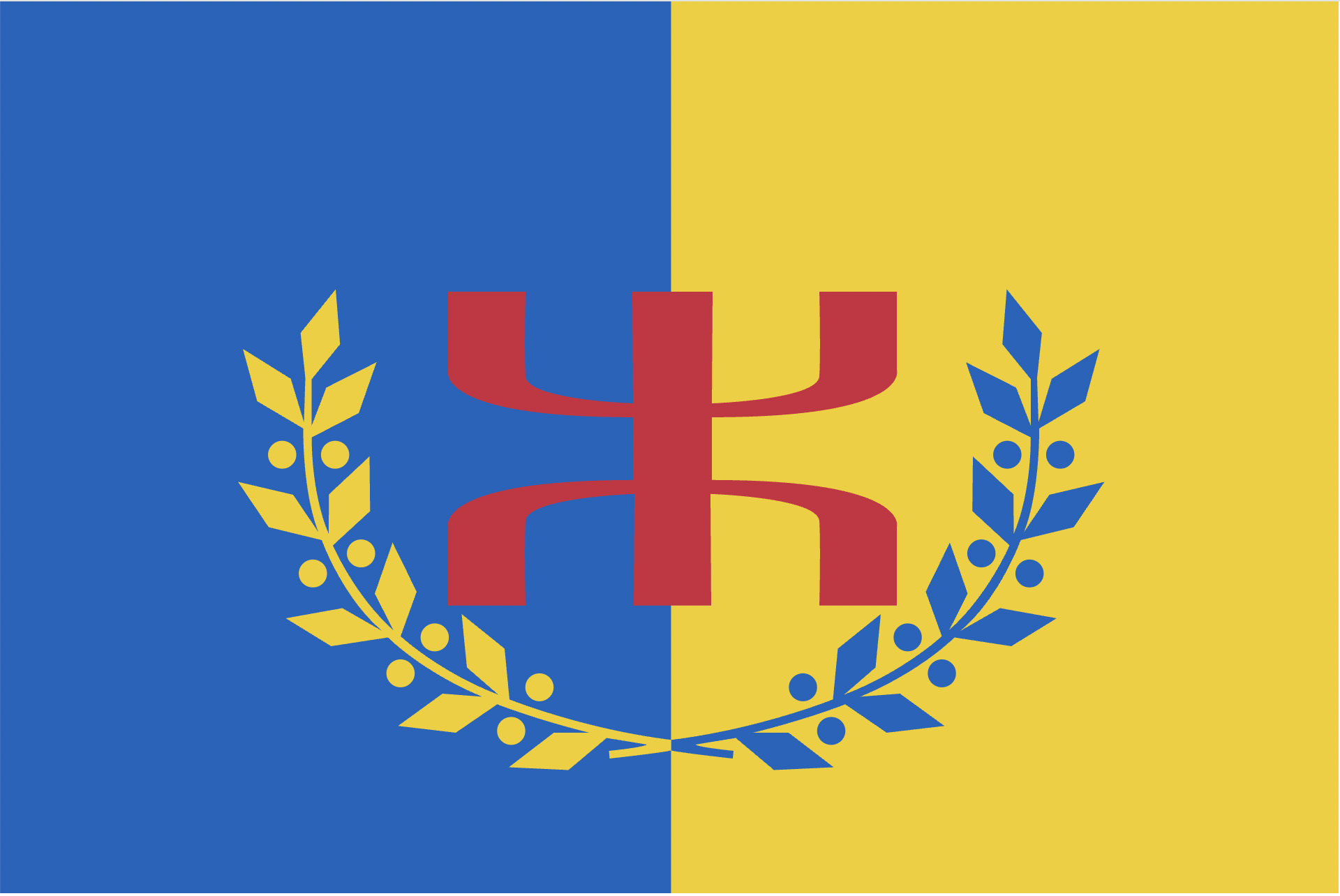

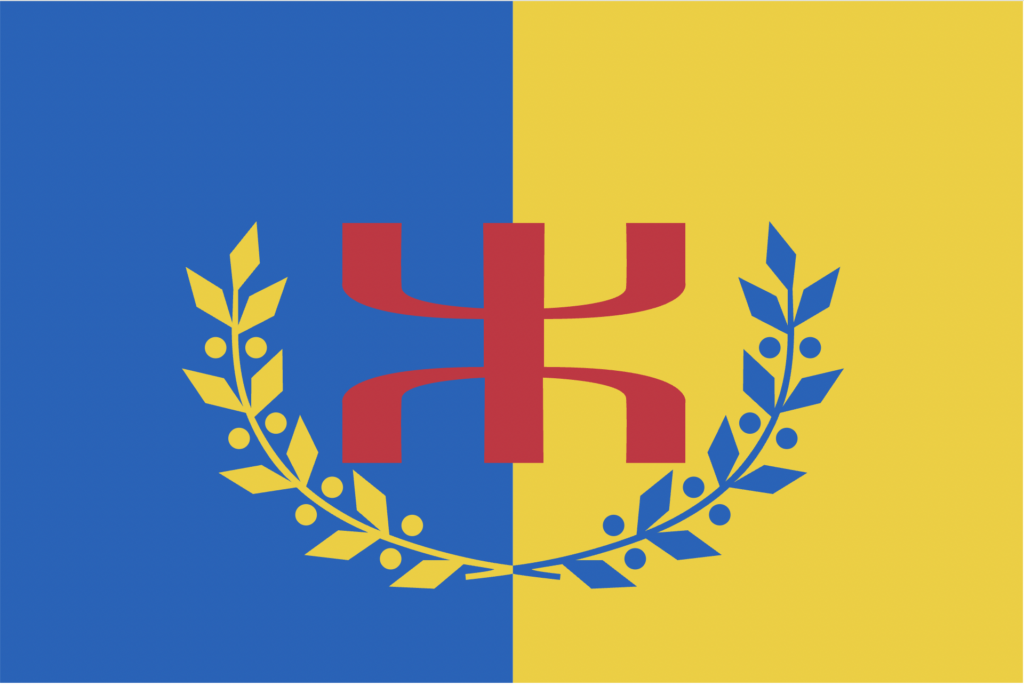

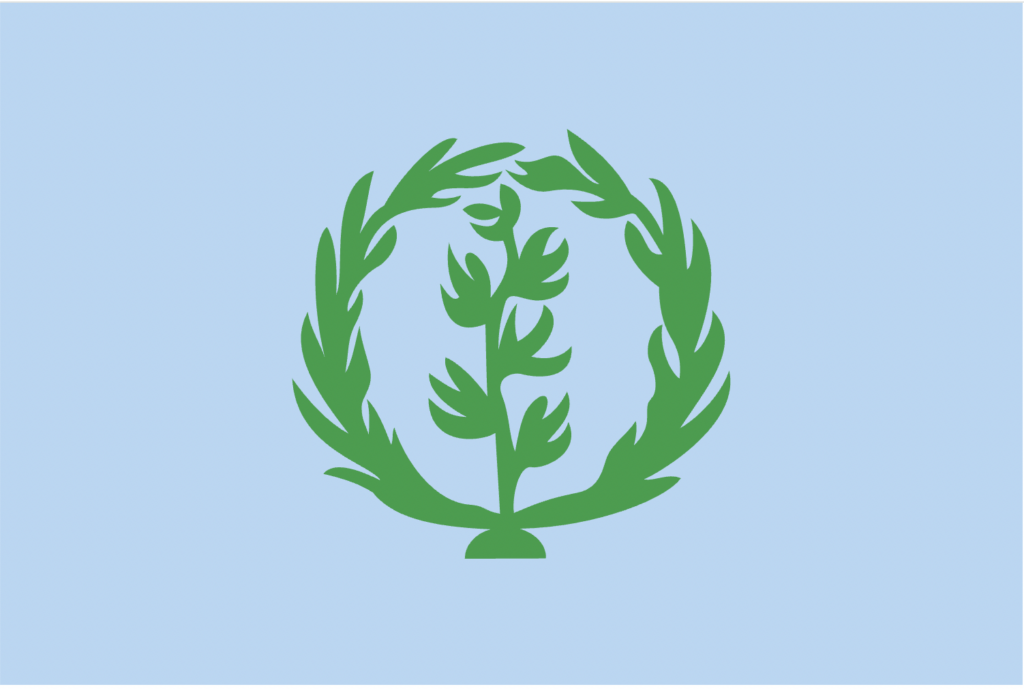

The Blue of the Brigade N’Hamedu refers to the azure flag of Eritrea from 1952 to 1962, a parenthesis of independence, when the former Italian colony was finally freed from successive mandates and formed a federation with Ethiopia, but before it was properly and simply annexed to the Ethiopian empire.

Exiled opponents of the regime have been warning for several years against single-party propaganda events disguised as cultural festivals in host countries. These festivals are a genuine assault on refugees who have already gambled their lives to escape the clutches of their persecutors. During the war in Tigray (2020–22) in neighbouring Ethiopia, Isayas Afewerki’s troops committed numerous war crimes. His unlawful intervention in Ethiopia only emboldened the PFDJ’s impunity abroad. Party leaders expressed themselves without restraint and in defiance of the law. A translation of the event’s speeches revealed incitement to violence and racial hatred. These events also serve as fundraisers for a beleaguered regime. Some countries such as the UK, Sweden, Canada, Switzerland reacted, but Germany let it happen. The Giessen festival on August 20, 2022, marked the point of no return, when tension turned into open fighting between those for and against the regime. The clashes were repeated in Stuttgart in 2023, then in 2024. Strangely, the Public Prosecutor’s Office has finally opened proceedings, but against the pro-democracy opponents.

Transnational repression

The Eritrean government uses its embassies and diplomatic missions as bridgeheads to spy on its nationals and blackmail them in exchange for identity documents they might need to obtain refugee status. They also threaten their families back home if they criticize the regime abroad or engage in political and civic activity outside the party line. It is therefore surprising that the German authorities allow PFDJ’s agents to act with impunity, even imposing heavy fines of several hundred thousand euros on pro-democracy opponents. The final straw is the terrorism investigation into the Brigade N’Hamedu, even though they have never threatened national security, the German state or population, not even verbally.

The Isayas regime is one of the Kremlin’s best allies on the African continent. It maintains criminal links with Russian networks associated with gold and arms trafficking. From 2014 onwards, Isayas and his lobbyists spread an ideology carried through Wagner’s channels across Africa stoking hatred of the West. The message has been summed up in the hashtag #NoMore, meaning ‘no more interference’, that became a rallying cry for haters promoting genocide in Tigray.

On August 13, 2022, a week before the Giessen festival and the same day that a similar festival was banned in Rijswijk in the Netherlands, Awel Seid, an Eritrean actor-singer who had become the Eritrean regime’s most famous champion, released a video entitled ‘No More!’ in which he directly attacked Swedish politician Asa Nilsson Sonderström, who had prevented fundraising in Stockholm. In his clip, Awel Seid pours out his hatred against opponents, Tigrayans and displays a threatening montage of international intellectual figures campaigning for human rights.

PFDJ meetings are nothing new. They used to be attended by the usual anti-Ethiopia party stalwarts, but with Awel Seid, the style changes radically. With a Rockstar look, eccentric clothing in the colours of the Eritrean flag (not the blue one, of course), rhythmic music and video montages, he exhibits a style taken up in 2024 by the so-called ‘Algerian influencers’.

The Algerian precedent

Another regime that has been practising transnational repression for a long time is Algeria. After years of civil war, the ruling regime holds the country solely by terror. It is also in permanent conflict with its neighbours, inventing fantastical plots linking Morocco, France and Israel to maintain the state of emergency, and thus arbitrariness. In addition, obsessive criticism of colonization has become Algerian government’s stock-in-trade, enabling it to blackmail France and cover up its own failure in domestic politics. Martial discourse, destabilization operations, and state paranoia make the parallels with Eritrea striking.

Algeria won its independence from French colonial rule in a bloody struggle. The Algerian war officially ended on 19 March 1962 with the Evian Accords. The country was then ruled by the Front de Libération Nationale (FLN) and sank into an authoritarian drift that was quickly denounced by the Kabyle-born leader Hocine Aït Ahmed. Imprisoned, he escaped and found refuge in Switzerland.

Arbitrary detentions, torture, enforced disappearances, the muzzling of all opposition and the militarization of society – the twisted FLN has undermined the liberation of Algerians. The party also extended its arm abroad. Targeted assassinations in European cities, passport blackmail, pressure on families back home – Algiers deploys all the paraphernalia of transnational repression. In this respect, Krim Belkacem’s assassination is more than symbolic; it is, in a way, the original sin of the Algerian regime. Indeed, Krim Belkacem was also a Kabyle figure in the independence movement and a signatory of the Evian Accords. But he opposed the other leaders of the FLN. Threatened and hounded, he was finally assassinated in 1970 in Frankfurt. ‘They killed the Kabyle who freed them’, an activist says.

Eritrean PFDJ equally experienced this fratricidal struggle within the liberator party, as Isayas Afewerki got rid of his fellow fighters, all of whom disappeared in the 10 years following independence.

Back in Algeria, Kabylia is a mountainous region in the northeast of the country, renowned for its rebelliousness, and the main Amazigh centre. It became the bastion of the struggle for democracy since Kabyle villages have historically governed themselves through customary law (qanun) and village assemblies (tajmaât). These institutions emphasize collective responsibility and local autonomy, fostering a participatory form of governance that contrasts with centralized state structures. Like the azure flag of the Blue Revolution, that of the Kabyle autonomous movement is itself a protest. Reproducing the yaz, meaning ‘free man,’ a stylized figure symbolizing the Amazigh peoples, it is still punishable by imprisonment.

Following the ban on a Berber poetry festival in 1980, the Amazigh peoples of Algeria revolted against the central government in Algiers and its policy of forced Arabization. The policy was imposed as a nationalized decolonization programme without considering the ethnic and linguistic particularities of the Algerian peoples. Harshly repressed, this revolt is known as the Berber Spring (Tafsut Imazighen) and would be followed by multiple uprisings, each drowned in blood. In 2001, after the Black Spring, Ferhat Mehenni founded the Movement for Self-Determination of Kabylia (MAK). The MAK is not just a community party. It is a pacifist movement which campaigns for the rights of peoples to self-determination and calls for democracy and universal values, regardless of one’s ethnic origin or religion. Faced with the impossibility of existing under a government that stifles minority rights, Kabyle leaders decided to create Anavad, the Kabyle government in exile to coordinate the resistance. The MAK was declared a terrorist organization in Algeria in 2021. Sentenced to death, its leaders, including Ferhat Mehenni (whose son was assassinated in Paris by the regime) and Aksel Bellabbaci, were forced seek refuge in France. On October 2, 2024, Algerian writer Boualem Sansal, who had just acquired French nationality, recalled a historical truth: that the Amazigh territories of eastern Algeria belonged to Morocco and were annexed to Algeria in the 19th century by the French colonial power. On November 16, 2024, Boualem Sansal was arrested in Algiers, held incommunicado, and on March 27, 2025, after a botched trial, was sentenced to five years in prison. Aged 75, suffering from cancer and left without care, it was a death sentence. But the Algerian regime has more than one trick up its sleeve and is offering France to exchange him for Aksel Bellabbaci, the leader of the MAK. Boualem Sansal must be released, but not at the cost of making him into a vile bargaining chip. The Sansal affair is the latest incarnation of a war of influence. And this is where the destinies of Algeria and Eritrea intersect.

Virtual soldiers, real violence

On February 27, 2013 General Valery Gerasimov, Chief of the General Staff of the Armed Forces of the Russian Federation, published an article in Military-Industrial Kurier. He begins by analysing new forms of conflict and the shift of violence being placed in the hands of non-military actors, drawing on the example of the Arab Spring. For him, these ‘conflicts’ are real wars, and that is how wars must now be viewed. They are hybrid and asymmetrical. The role of non-military means in achieving political and strategic objectives has grown, and in many cases, their effectiveness has surpassed that of military force. He recommends widening social divides and relying on agitators as proxies.

While the term ‘Gerasimov doctrine’ is a misnomer, it is a fact that Russia and its allies are wielding hybrid warfare. If Eritrea enjoys strong relations with Russia, the same goes for Algeria, which imports more than 80% of its military equipment from Russia, making it the third largest global customer of Russian arms. In September 2022, the Algerian army general staff participated in a massive military exercise in Vostock under the leadership of General Gerasimov himself. A few months later, it was in Algeria, in Béchar near the Moroccan border, that Russian officers led the manoeuvre. In September 2024, Vladimir Putin sent his congratulations to Abdelmadjid Tebboune on his re-election, expressing ‘his wish to raise the Declaration of Deep Strategic Partnership, signed last year between Algeria and Russia, to a higher level’.

The use of influencers on TikTok and other social media platforms is the latest trend for totalitarian regimes. I mentioned the figure of Awel Seid for Eritrea, but the virtual soldiers of Asmara are numerous on the networks. Always with the same tone, the same insults, showing off weapons or miming throat-slitting, Algeria followed suit at the end of 2024. A wave of influencers flooded French and Arabic networks, calling in foul language for the killing and rape of opponents, Jews, and all their allies on French territory. As reported by Kabyle whistleblower Chawki Benzehra, this is a coordinated offensive from Algiers, a fact confirmed by France 2 television reporters who infiltrated Algerian diplomatic missions.

For both the Algerian and Eritrean governments, the aim is to recruit people who can speak to young people who sometimes struggle to find their place in their host country and who may have encountered racism.

Lessons learned

Long paralyzed by its colonial past, France is now taking a firm stand against Algiers’ provocations and a Defense Council dedicated to Algeria has been created. On April 1, Ferhat Mehenni, Aksel Bellabbaci, and a MAK delegation were received at the French Senate. The release of Bouallem Sansal was at the heart of the discussions, but as one MAK official pointed out, there are hundreds of Kabyle political prisoners, some of whom are on hunger strike. They must not be forgotten.

In early April, the blogger Amir DZ, highly critical of the regime in Algiers, was kidnapped in the Paris region and held for three days by the Algerian secret service. The case is being taken very seriously in Paris and has been entrusted to the domestic intelligence service (DGSI) and the anti-terrorist service (SDAT). Furthermore, a dedicated service has been established to protect victims of transnational repression. Germany undoubtedly still lacks experience in this area, but it would benefit from drawing inspiration from its neighbour. For now, the Federal Public Prosecutor’s decision to investigate the Brigade N’Hamedu, while adopting a complacent attitude towards PFDJ agents, demonstrates a desire to treat the symptom rather than the cause of the problem. Indeed, one may question the intent and publicity surrounding the March 26 operation. Were the warrants inspired by Asmara’s agents in Germany? Some community associations are well-known for being PDFJ lobbies abroad. Or were they pledges given to the populist far-right to cast aspersions on all refugees and, by extension, visible minorities in Germany?

Dawit Isaak and Boualem Sansal are the faces of repression. But there are thousands of them, less famous. When a population is deprived of its physical and intellectual integrity in its own country, the only thing left is resistance abroad.

European cooperation should play a role, and Germany could benefit from France’s experience in dealing with transnational repression on its territory. It is also time to see the latter for what it is: infiltration in favour of hostile countries, a violation of national sovereignty, a form of hybrid warfare. At a time when European defence has been on everyone’s lips since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and Donald Trump’s announced withdrawal from Europe, it is imperative to realize that the threat is not only deployed on the Eastern Front with conventional weapons.

As for the two-year-old Brigade N’Hamedu, it is still in its infancy. If we want to see it take the path of pacifism, democracies cannot turn their backs on it. It would be wiser to turn these young people into interlocutors rather than driving them underground.