DN Kultur – Dawit Isaak

BJÖRN TUNBÄCK: Why is Sweden not investigating Dawit Isaak’s imprisonment as a human rights violaton?

July 11, 2024

Ten years have passed since Dawit Isaak’s case became a subject for the Swedish judicial system. But so far, Sweden has refused to initiate an investigation of crimes against humanity, writes Björn Tunbäck, board member of Reporters Without Borders.

-Don’t you have an independent judiciary in Sweden?

I was asked this question many years ago in The Gambia, where the African Human Rights Commission was meeting. One of the continent’s leading lawyers in the field looked up in surprise after reading a decision by Sweden’s Prosecutor General. That was his response to a complaint from Dawit Isaak’s legal team – Jesús Alcalá, Percy Bratt and Reporters Without Borders’ then legal director Prisca Orsonneau. Ten years ago, they filed a complaint against Eritrean President Isaias Afwerki, his advisers and several of his ministers for, among other things, crimes against humanity in the case of Dawit Isaak.

They were supported by the law against genocide and crimes against humanity that the Riksdag had just passed.

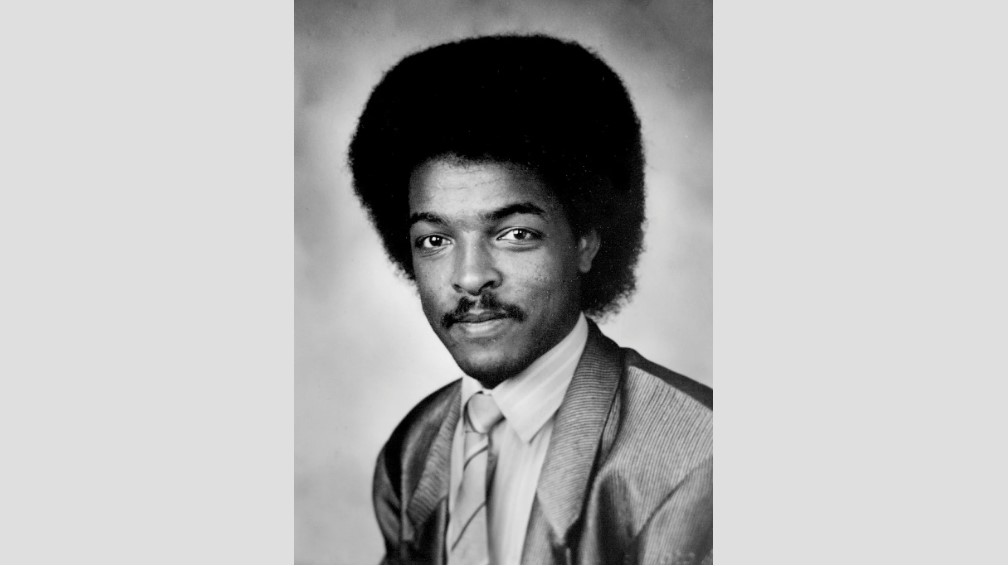

At that time, it had been 13 years since the journalist and author Dawit Isaak was arrested in Eritrea. He is being held in prison without charge, without seeing his family, without access to an attorney, in solitary confinement, and without the regime providing information where he is imprisoned. This constitutes a crime against humanity.

This was also exactly what the Prosecutor General (RÅ) suspected when he responded to the complaint. In his several pages long decision, he also said that the suspicions could be investigated by the Swedish police.

That was not what made the African human rights expert react – it was the [SPG’s] conclusion.

In it, the SPG explains that he consulted the Swedish Ministry of Foreign Affairs and concluded that a preliminary investigation would disrupt the Foreign Ministry’s negotiations to secure Dawit’s release. Therefore, it was best not to investigate the suspicions of a crime, according to the SPG.

Since then, Dawit Isaak has survived another ten years of solitary confinement in Eritrea’s life-threatening prison archipelago. He turns 60 this autumn. When he was arrested, he was 36. A young man is approaching retirement.

At the same time, we see that the Ministry for Foreign Affairs’ work has not yielded results. No other efforts either. It is the regime in Asmara that is responsible, but when will the law be allowed to take its course? When will Swedish law enforcement authorities take up the case?

It is not certain that a criminal investigation against the Eritrean leadership will lead to Dawit Isaak being freed. But silent diplomacy has not achieved this either. In two decades.

When the Swedish government recently exchanged the convicted Iranian [law] criminal Hamid Noury for two Swedes Iran had taken hostage, top-level Swedish officials said that they had not been able to help a third Swedish prisoner, Ahmedreza Djalali, a physician sentenced to death in 2017. They could not include him in the swap because Iran refuses to accept his Swedish citizenship. It seemed like the Swedish government accepted this position. It is ominous. The situations are not identical, but Eritrea uses exactly the same arguments against Dawit Isaak. As does China in the case of publisher Gui Minhai.

Swedish prosecutors have shown that they can investigate human rights violations committed in other countries. It happened in the case of Hamid Noury and as recently as July 3rd, three people were arrested on suspicion of serious violations of international law in Syria.

Right now, the UN Human Rights Council is meeting in Geneva. In his report to the meeting, the Council’s Special Rapporteur on Eritrea [Mohamed Babiker] describes how the Eritrean regime oppresses its population and says that the repression also extends beyond the country’s borders. A UN commission has called on countries to act and investigate suspected human rights violations. Several prominent international lawyers have supported a new complaint in Dawit Isaak’s case, including a former judge of the International Criminal Court, a former chairman of the African Commission on Human Rights, Canada’s former Minister of Justice Irwin Cotler and Nobel Peace Prize winner Shirin Ebadi.

So far, Sweden has said no. But it is no longer possible to hide behind the argument that it risks disrupting silent Swedish diplomacy.