Source: South China Morning

The East African nation and fellow Brics member is the latest country to seek a switch, accelerating the yuan’s internationalisation.

Ethiopia’s plan to convert its dollar-denominated Chinese loans to yuan is a “savvy financial arbitrage play” in the view of some analysts, while others warned that the move could “complicate” negotiations with bondholders over the 2023 Eurobond default.

Eyob Tekalign, governor of the Ethiopian central bank, confirmed last week that Addis Ababa had initiated talks with Chinese lenders, including the Export-Import Bank of China (China Eximbank) and the People’s Bank of China, to swap part of its US$5.38 billion loans with them into yuan.

The currency swap – which follows a similar move by Kenya earlier this month – could cut the interest from 7.25 per cent to just 3 per cent, offering a critical fiscal lifeline to the East African nation as it negotiates the restructuring of about US$15 billion of external debt.

Kenya converted US$3.5 billion of its Chinese loans into yuan, earning US$215 million in annual savings on debt-servicing costs and playing into China’s game plan to accelerate internationalisation of the renminbi.

Tekalign, who was in Washington for the annual meetings of the World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF), said Ethiopia had asked for the debt swap when he was in Beijing in September – continuing a trend that has also seen Sri Lanka and Hungary turn to the Chinese currency for cheaper finance.

A memorandum of understanding (MOU) was also signed to advance Addis Ababa’s debt restructuring under the G20 Common Framework – a key step towards negotiations and the alleviation of Ethiopia’s debt burden, according to its embassy in Beijing.

Speaking in Washington, Tekalign said the currency swap “really makes sense”, given the rising trade and investment between Ethiopia and China. According to Chinese customs data, China is Ethiopia’s largest trading partner, with total two-way trade standing at US$3.55 billion last year, a 17.5 per cent year-on-year increase.

While easing Ethiopia’s debt crisis, the yuan-denominated swap risked complicating the stalled talks with Eurobond holders who are demanding comparable creditor treatment, according to analysts.

Naeem Aslam, chief investment officer at London-based Zaye Capital Markets, said Ethiopia’s yuan swap plan was more than “just a ledger tweak”.

Aslam called it “a savvy arbitrage play on interest rate differentials and currency volatility, buying fiscal breathing room amid a US$15 billion external debt overhang and the 2023 Eurobond default hangover”.

He said that the move mirrored Kenya’s recent railway loan conversion, which was already shaving substantial amounts off annual service costs, underscoring a ripple effect by aligning repayments with bilateral trade flows, where China loomed large as Ethiopia’s top trading partner.

According to Aslam, this would help Addis Ababa hedge against dollar scarcity and foreign exchange shocks, and potentially “unlock IMF nods for broader relief under the G20 Common Framework”.

He cautioned that while immediate savings could fuel a 7.2 per cent gross domestic product rebound and infrastructure resuscitation, the deal deepened Ethiopia’s “gravitational pull towards Beijing, trading short-term mercy for long-haul dependency”.

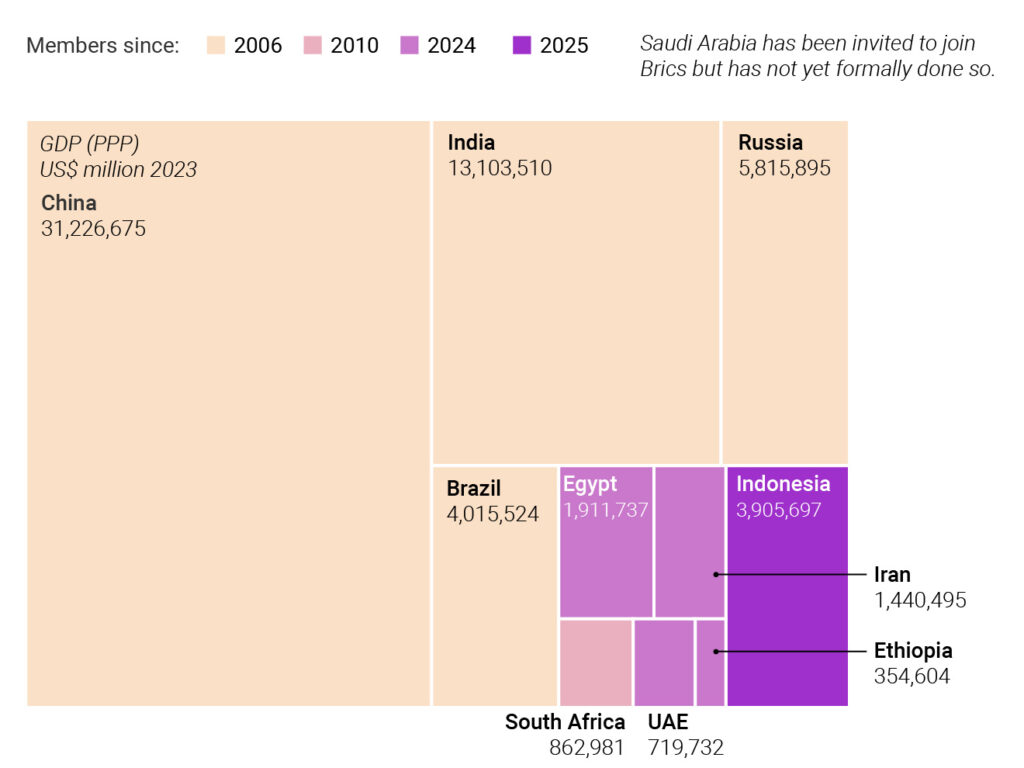

Ethiopia is a member of Brics – an acronym for the association’s founding members of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa. The group has grown to include 10 leading emerging markets, all pushing for de-dollarisation.

Expanding Brics

The move has prompted US President Donald Trump to threaten tariffs on Brics members, which also include Egypt, Indonesia, Iran and the United Arab Emirates.

Yufan Huang, a pre-doctoral fellow with the China-Africa Research Initiative at the Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies, said that while the savings were an understandable goal, the swap might not happen quickly.

With China Eximbank at the stage of finalising the MOU for its Common Framework debt treatment for Ethiopia, the currency swap could complicate Addis Ababa’s deal with the bondholders.

“It is difficult to know how [the currency swap] would affect the comparability of treatment calculation and therefore affect Ethiopia’s deal with the bondholders,” Huang said.

Ethiopia, the continent’s second most populous nation, is a key destination for Chinese financing, securing about US$14.5 billion from China between 2000 and 2023 for major infrastructure projects.

These have included Belt and Road Initiative projects such as the US$4.5 billion Addis Ababa-Djibouti Railway, the capital’s light-rail network and the Riverside Green Development Project, according to Boston University’s Global Development Policy Centre.

Chinese firms also hold vast investments in Ethiopia’s light manufacturing industry and were contracted to build parts of the US$4.6 billion Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam.

But Ethiopia fell into a financial mess amid the coronavirus pandemic and a two-year civil war in the northern Tigray region, leading to the default on its US$1 billion Eurobond in 2023 and subsequent request for debt relief under the G20 Common Framework.

While its largest bilateral lenders, notably China, agreed to interim relief, talks with private bondholders hit a snag and were stalled by disagreements over terms, according to the Ethiopian government.

For China, the currency swap was “yuan rocket fuel”, boosting renminbi internationalisation and fortifying belt and road ties without the geopolitical static of outright forgiveness, according to Aslam.

Lesetja Kganyago, South Africa’s central bank governor, last week said that converting dollar debts into lower interest renminbi liabilities was “part of the bigger Chinese strategy of internationalising the yuan”.

Aslam suggested that Zambia, with its copper-rich exports to China, was the “front runner to follow suit” after Kenya. Lusaka, which was already pioneering yuan clearing hubs, was “primed to convert dollar drags into bilateral ballast next”, he said.

Zambian Finance Minister Situmbeko Musokotwane recently indicated that Lusaka was closely monitoring Kenya’s deal, Aslam noted.

But Tim Jones, policy director at the British-based charity Debt Justice, argued that transferring debt to yuan would still leave debtor countries with significant exchange rate risks.

He said a much better option would be for debts to be owed in the local currency of the debtor.

“Ethiopia needs large-scale debt cancellation,” he said, adding that all creditors must agree to deeper relief, and bondholders had been the most disruptive creditors by refusing a generous restructuring offer.