Source: The Africa Report

The fragile stability that followed the 2018 peace accord has evaporated, leaving the region’s two most powerful militaries locked in a dangerous new standoff.

Are Ethiopia and Eritrea actually about to renew hostilities – and will they drag in the rest of the region?

Why has the war question returned now?

Because three tracks are converging. First, Ethiopia’s post-Tigray settlement is fraying again. The UN secretary-general’s spokesperson, Stéphane Dujarric, warned on 31 January of renewed tensions in Tigray and the “risk of a return to a wider conflict” in a region still rebuilding.

Second, Addis Ababa and Asmara have shifted from cold suspicion to formal, public accusation. Third, the Horn is being pulled into the Gulf rivalry and Sudan’s war – a context in which crises escalate faster and mediation is harder.

What are the clearest warning signs between Ethiopia and Eritrea?

The strongest signals are diplomatic – because they lock leaders into positions.

On 8 February 2026, Ethiopia’s foreign minister, Gedion Timothewos, accused Eritrea of “military aggression”, saying Eritrean forces were occupying Ethiopian territory, and demanded their “immediate withdrawal”.

However, a day later, Eritrea’s information ministry termed the allegations as “false and fabricated”, framing them as part of a hostile campaign.

Addis is also building a proxy-war case. Reuters reported on 15 January that Ethiopian federal police said they had seized 56,000 rounds of ammunition in Amhara and alleged it was sent by Eritrea to rebels, escalating the war of words.

On the narrative front, the tone has hardened. AP reported in early February that Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed formally accused Eritrean troops – for the first time – of mass killings during the Tigray war. But Eritrea’s information minister, Yemane Gebremeskel, rejected these accusations as unfounded.

Are troops actually massing – or is this still mostly rhetoric?

Open-source proof is uneven. Images of lorries commandeered to carry Ethiopian troops to the north posted on social media have cropped up, but credible reporting points to possible military preparation.

Reuters reported in March 2025 that Eritrea had ordered a nationwide mobilisation in mid-February 2025, citing a human-rights group, and that Ethiopia had deployed troops toward the Eritrean border, citing diplomatic sources and Tigrayan officials. Reuters also noted it could not independently verify some claims about deployments.

When both sides are mobilising, any incident – a border patrol clash, a militia attack attributed to the other side – could touch off conflict.

What is the dispute really about – borders, Tigray, or the Red Sea?

All three. Tigray is the tripwire; the Red Sea is the strategic prize.

Reuters reported in March 2025 that Abiy called sea access an “existential” issue for landlocked Ethiopia while emphasising that it had “no intention” of going to war with Eritrea to obtain it. But Eritrea reads the rhetoric differently, particularly because the most obvious Eritrean asset is the port of Assab. When sea access is framed as existential on one side, and sovereignty on the other, compromise becomes politically costly.

Tigray then turns that strategic dispute into an operational problem: instability in northern Ethiopia creates space for proxy claims, cross-border allegations and opportunistic moves.

So how does the rest of the region get dragged in?

The Horn is no longer a closed system – it is now plugged into Sudan’s war and a Saudi–UAE contest.

Reuters’ investigation, published on 10 February, reported that Ethiopia is hosting a secret camp in Benishangul-Gumuz near Sudan to train fighters for Sudan’s Rapid Support Forces (RSF), citing multiple sources and satellite imagery.

Reuters reported that eight sources – including Ethiopian officials and diplomats – said the UAE financed and supported the camp; the UAE has denied involvement. This matters for Ethiopia–Eritrea because it links Ethiopia more tightly to Abu Dhabi’s regional posture at the same time as Eritrea seeks counter-weights.

Reuters reported on 2 February that Egypt deployed Turkish-made Bayraktar Akinci combat drones to a remote airstrip near Sudan, citing officials, experts and satellite imagery – a sign Cairo was being drawn deeper into Sudan’s war.

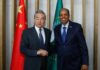

But this is not a recent phenomenon. In October 2024, Egypt, Eritrea and Somalia agreed to boost security cooperation – a development that could leave Ethiopia more isolated amid its disputes with Somalia and Egypt. One year later, the office of Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi said he had received Eritrean President Isaias Afwerki in Cairo for talks on bilateral ties and regional issues.

Rivalry within the Gulf creates an additional layer. Saudi–UAE competition has spread across the Red Sea into Somalia, and Sudan. Discord between Ethiopia and Eritrea mounts, with diplomats describing pressure to “choose a side” and experts warn of proxy dynamics.

Will they actually go to war? What are the brakes?

A full-scale interstate war is not inevitable. Both regimes have strong reasons to avoid a large, open conflict: Ethiopia is managing internal insurgencies and fiscal strain; Eritrea’s model relies on tight domestic control and would face high costs in a prolonged conventional fight.

But the risk of a limited clash is real – and the regional environment makes escalation more likely. The most plausible pathway is not a formal declaration; it is a chain of incidents and reprisals amid mobilisations, proxy accusations and outside patrons.

What should we watch next?

Four focal points are key: (1) verified new deployments along the Eritrean frontier; (2) further formal ultimatums like Ethiopia’s ‘immediate withdrawal’ demand; (3) additional evidence of proxy pipelines – weapons seizures, arrests, or imagery; (4) sharper alignment moves – new security pacts, base access, or drone and air-defence positioning tied to Sudan spillovers.