Source: ifa.gov

Author: Amanuel Taddesa

Introduction

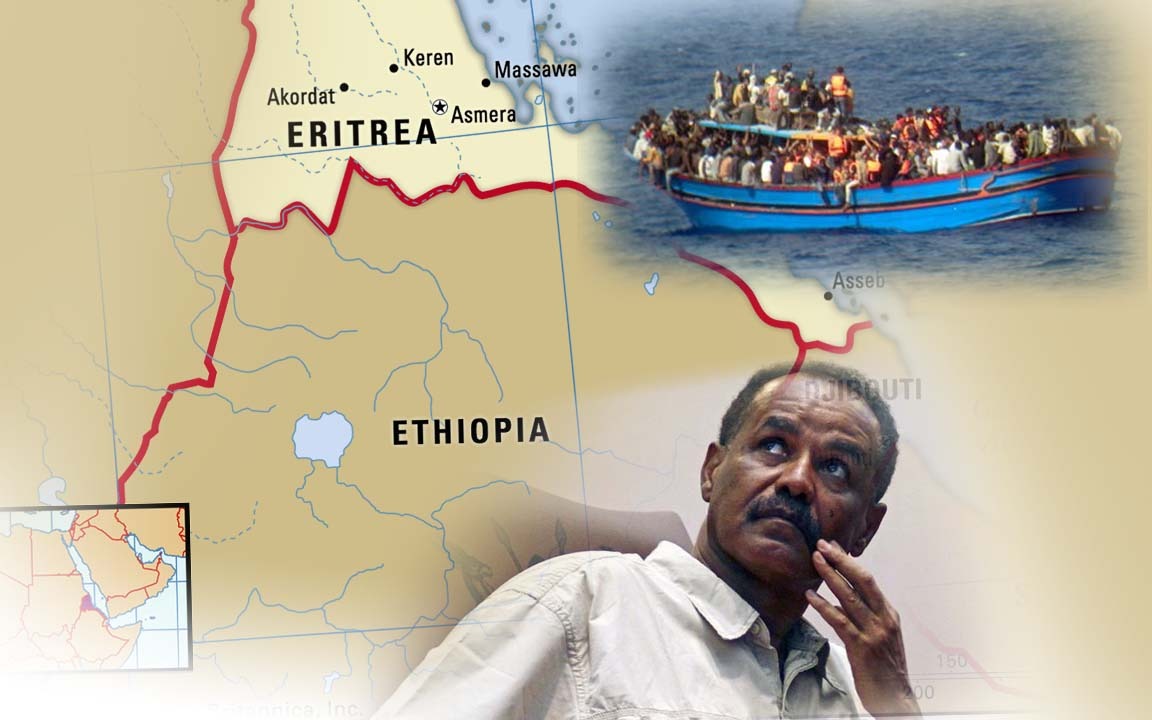

During its armed struggle for independence, the Eritrea’s People’s Front for Democracy and Justice (PFDJ) had promised to build an ambitious “African Singapore” economic model, coupled with the Scandinavian-inspired social welfare, and an Israel-style military architecture. Pivotal to this vision were party-controlled state enterprises, most notably the Red Sea Trading Corporation and the Hidri Trust conceived as instruments of post-war reconstruction, distributive justice, and national self-reliance.

Three decades later, this vision has utterly collapsed. Rather than serving as development engines, these entities have evolved into the financial and logistical backbone of a deeply entrenched predatory kleptocracy. Operating beyond public oversight and outside any meaningful legal accountability, they facilitate illicit financial flows, forced-labor exploitation, sanctions evasion, and regional destabilization.

This policy brief argues that the failure of Eritrea’s African Singapore project is neither accidental nor capacity-driven. It is the product of a deliberate institutional design that weaponized state-owned enterprises to ensure regime survival, enable the clandestine enrichment of the PFDJ clique, suppress domestic political dissent, geopolitical manipulation, and embed within transnational criminal and conflict economies.

The Singapore Development Model: Institutional and Ideological Foundations

Singapore represents a paradigmatic case of post-colonial development success. Despite its limited territory and absence of natural resources, it transformed itself into a high-income global economic hub through institutional coherence, meritocratic governance, and outward-oriented economic strategy. Under the People’s Action Party and the principal architect of modern Singapore Lee Kuan Yew (1959-1990), Singapore prioritized political stability, administrative professionalism, and pragmatic policymaking anchored in measurable economic and social outcomes.

Institutionally, Singapore built a professional civil service insulated from patronage through merit-based recruitment, competitive remuneration, and strict accountability mechanisms. A zero-tolerance approach to corruption, underpinned by the rule of law and transparent public finance, created a predictable and credible governance environment. Economically, Singapore pursued export-led growth, deep integration into global trade networks, and strategic attraction of foreign direct investment. Human-capital development though education and skills training reinforced social cohesion and productivity gains. This institutional architecture, rather than authoritarian discipline alone, explains Singapore’s sustained development trajectory within six decades (World Bank, 2025).

Eritrea’s leadership has repeatedly invoked Singapore as an aspirational reference point. Yet, beyond rhetorical appropriation and notwithstanding superficial similarities in territorial size and strategic location, Eritrea’s post-independence trajectory diverged sharply from the institutional and ideological foundations that rendered the Singapore model viable. Under the PFDJ, Eritrea evolved into a militarized, opaque, and inward-looking political economy, systematically eroding market openness, rule-based governance, and institutional accountability. The following sections illustrates how this divergence crystallized through party-controlled conglomerates, most notably the Red Sea Trading Corporation and its affiliated entities.

The Red Sea Trading Corporation: From State Enterprise to Transnational Criminal Hub

The Red Sea Trading Corporation (“09”) was established in 1984 and legalized under Proclamation to Establish Red Sea Trading Corporation No. 29/1993 as a state-owned commercial entity mandated to import, export, and distribute essential goods at affordable prices. Its statutory purpose emphasized public welfare, price stabilization, and economic reconstruction.

In practice, the Corporation has fundamentally departed from this statutory mandate. Effective control shifted from formal governance structures to the PFDJ leadership, notably under the direction of Hagos Gebrehiwet (Wedi Kisha), President Isaias Afwerki’s principal economic adviser. Despite legal provisions requiring board oversight and social redistribution including the allocation of one-third of profits to families of fallen fighters-revenues were systematically diverted to party-controlled entities.

Over time, the Corporation evolved into a parallel economic structure operating entirely outside the national budgets, public audit, and parliamentary scrutiny. Reports of the UN Monitoring Group document the Corporation’s central role in monopolizing imports-exports, foreign exchange, procurement of military equipment, and evading international sanctions through offshore networks and hard-currency laundering in the Red Sea and Gulf Regions. Eritrean diplomatic missions reportedly facilitated these activities, transforming a nominal state enterprise into a transnational revenue-extraction apparatus. Rather than advancing national development, the Corporation now function as a core financial engine sustaining elite enrichment, domestic repression, and regional destabilization across the Horn of Africa and the wider Red Sea corridor.

The Hidri Trust: From Social Welfare Instrument to Illicit Financial Regime

The Hidri Trust was established in 1994 to support the survivors of Eritrea’s armed struggle, with its mandate reinforced by Proclamation No. 48/1994 and the Martyr’s Survivors Benefit Proclamation No. 137/2003. These instruments guaranteed monthly financial support to families of fallen fighters in the amount of 500 Nakfa.

Instead, the Trust was transformed into the clandestine financial nucleus of the PFDJ system. While official submissions to the UN Human Rights Council claimed annual welfare expenditures exceeding USD 20.73 million, empirical evidence indicates that assistance was discretionary, opaque, and conditioned on political loyalty rather than legal entitlement.

Under the effective control of Wedi Kisha and security-linked operatives, the Hidri Trust evolved into a sophisticated transnational financial network encompassing offshore banking, mining revenues, diaspora taxation, and arms procurement, and logistics. Its revenue streams rely heavily on compulsory 2% diaspora taxes, illicit transfers, and shell companies operating across the Gulf and East Africa.

Functionally, the Trust no longer resembles a welfare institution. It operates as a coercive economic regime, conditioning access to livelihoods on political compliance and providing the financial backbone for systemic repression. Together with affiliated conglomerates such as Himbol Financial Services, Transhorn Transport PLC, Eri-Equip, and the Anderbeb Share Company, it exemplifies the subordination of formal state institutions to opaque party-controlled financial networks.

Why the Singapore Model Aborted in Eritrea: From a Developmental Dream to Predatory Kleptocracy

- Absence of Strong and Autonomous Institutions

Singapore’s development success rested on institutional autonomy, transparent fiscal governance, and adherence to the rule of law. Eritrea exhibits the opposite configuration; undisclosed national budgets, absent regulatory oversight, and total centralization of economic decision-making in the Office of the President. Judicial bodies and ministries function as extensions of executive power rather than autonomous institutions. This institutional vacuum enabled party-owned conglomerates to operate as unregulated instruments of elite enrichment.

- Forced Labor as a System of Modern Slavery

While Singapore growth strategy anchored on human-capital development and competitive labor markets, Eretria inverted this model by institutionalizing forced labour through indefinite national service. Under the Warsay-Yikealo Development Campaign, conscripts are routinely deployed as unpaid labour in PFDJ-owned enterprises. The UN Commission of Inquiry on Human Rights on Eritrea (2015) explicitly classified this system as a form of modern slavery under international human rights law.

- Command Economy and Party Monopoly

Singapore’s hybrid capitalism combined competitive markets with professionally managed state enterprises. Eritrea instead constructed a command economy dominated by party monopolies controlling banking, foreign exchange, imports-exports, and remittances. Financial institutions lack autonomy, credit allocation is politically determined, private enterprise is systematically excluded, and illicit remittance networks flourish rendering the economy vulnerable to money laundering and organized crime.

- Rejection of Regional Integration

Singapore’s rise was inseparable from regional integration through ASEAN. Eritrea pursued isolationism and a militarized foreign policy, weaponizing its geography to destabilize neighbors, and replacing economic diplomacy with conflict-based rent extraction. Reports by the UN Monitoring Group document Eritrea’s support for armed groups across the region, embedding criminalized networks within neighboring economies.

- Weaponizing the Red Sea: From Economic Gateway to a Criminal Maritime Corridor

Singapore has transformed its geostrategic maritime position into an economic multiplier through robust institutional design, legal certainty, and strict regulatory oversight. Major ports such as the Port of Singapore, Pasir Panjang, and Tuas operate within a governance framework that deliberately precludes their use as transnational criminal maritime corridors. Port governance in Singapore is characterized by a clear functional separation between commercial administration, regulatory oversight, and security enforcement. The Maritime and Port Authority of Singapore operates under clear statutory mandates subject to judicial and parliamentary oversight, ensuring transparency, predictability, and investor confidence.

Eritrea, despite possessing comparable geostrategic advantages along the Red sea, has adopted an antithetical governance model. Rather than institutionalizing the ports of Massawa and Assab as commercially autonomous gateways supported by credible legal and regulatory frameworks, port governance has been centralized under the Red Sea Trading Corporation and affiliated entities directly subordinated to the ruling party. In this system, commercial imperatives have been subordinated to security control and revenue extraction, eroding the economic functionality of the ports. As a result, Eritrea’s ports lack the core attributes of viable functional economic gateways, including regulatory transparency, investor protection, customs predictability, and institutional separation between commercial operations and security agencies. UN Monitoring Group reports have repeatedly documented irregular shipping practices linked to Eritrean ports, including cargo mislabeling, concealment techniques, and opaque logistics chains consistent with illicit procurement and sanctions evasion networks.

Rather than serving as engines of trade, integration, and development, the port of Massawa and Assab have been repurposed as nodes within a transnational criminal maritime system. This transformation illustrates how the absence of institutional accountability and rule-based port governance can convert strategic maritime assets from economic gateways into instrument of illicit activity, with destabilizing implication for Red Sea security and regional commerce.

- Shadow Transnational Economic Networks in East Africa: A Regional Security Risk

East Africa is increasingly exposed to transnational economic networks operating outside legal and regulatory frameworks. These networks distort markets, erode state authority, and pose a growing regional security risk, particularly in fragile and post-conflict settings. In contrast to regulated models of international economic integration, such as Singapore’s outward expansion through legally accountable multinational enterprises, Eritrea has externalized a criminalized political economy into the region. Economic activities linked to the ruling PFDJ function as extensions of an authoritarian party-state, rather than as lawful market actors integrated into regional economies. Intelligence assessments indicate the presence of Eritrean-linked entities in strategic sectors in Kampala, Uganda, including hotels, real estate, transport, and import-export businesses, and in Juba, South Sudan in hospitality, logistics, money-transfer services, and the liquor trade. Their placement in these sectors enables access to hard currency, control over logistics, and exploitation of weak regulatory environments. These networks rely on coercive labour practices targeting Eritrean nationals abroad, systematic bribery of host-state officials, money laundering through offshore hubs such as Dubai and Jeddah, and informal remittance systems that bypass national financial controls. Such methods facilitate sanctions evasion, undermine financial integrity, and embed organized crime dynamics within local economies. This pattern is not ordinary diaspora entrepreneurship or foreign investment. It reflects the outward projection of a state-backed coercive economic system designed to sustain regime survival through illicit financial flows. The result is the erosion of host-state governance, distortion of legitimate commerce, and amplification of corruption and organized-crime risks across East Africa. If left unaddressed, these networks risk entrenching illicit financial ecosystems, weakening regional integration, and aggravating insecurity in already fragile states.

From a policy implications perspective, addressing Eritrea’s entrenched kleptocratic political economy requires coordinated, legally grounded international action based on the following approaches:

- Targeted Financial Disruption: International engagement should prioritize the dismantling of the financial and logistical infrastructures that sustain the regime’s coercive reach. This necessitates targeted, intelligence-led sanctions against the Red Sea Trading Corporation, the Hidri Trust, and their offshore affiliates, with a focus on shipping insurance, corporate registries, and financial institutions rather than symbolic measures.

- Diplomatic Oversight: there is a need for robust monitoring of embassy-linked financial channels, which have long functioned as shadow fiscal, procurement, and coercive hubs under the guise of diplomatic activity. Enhanced scrutiny, consistent with the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (VCLT), particularly with respect to the abuse of privileges for non-diplomatic commercial and coercive purposes, should form part of a coordinated response among host states.

- Regional and Multilateral Coordination: Cooperation among IGAD, the Africa Union, the European Union, and the United States, and other partners should be strengthened to trace illicit financial flows, enhance maritime oversight in the Red Sea corridor, and prevent criminalized capital from entering regional development initiatives.

- Conditional Engagements: International actors should recalibrate engagement strategies to avoid inadvertently legitimizing and financing coercive structures through development aid, migration arrangements, and security cooperation.

References

- Africa Organized Crime Index. (2023). Africa organized crime index 2023. https://ocindex.net/

- Awate. (n.d.). A mafia group masquerading as lawful government. https://awate.com/a-mafia-group-masquerading-as-lawful-government/

- Chu, Y. W. (Ed.). (2016). The Asian developmental state: Reexaminations and new departures. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-0085-1

- Emerging Europe. (n.d.). The Singapore model: What CEE and the world can learn. https://emerging-europe.com/opinion/the-singapore-model-what-cee-and-the-world-can-learn/

- Evans, P. (1995). Embedded autonomy: States and industrial transformation. Princeton University Press.

- Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime. (2023). Global organized crime index 2023. https://ocindex.net/

- International Monetary Fund. (n.d.). Eritrea: Article IV consultation—Staff report. https://www.imf.org/en/Countries/ERI

- Johnson, C. (1982). MITI and the Japanese miracle: The growth of industrial policy, 1925–1975. Stanford University Press.

- Killion, R. (1998). Historical dictionary of Eritrea. Scarecrow Press.

- Lee, K. Y. (2000). From third world to first: The Singapore story. HarperCollins.

- Low, L. (1998). The political economy of a city-state: Government-made Singapore. Oxford University Press.

- Low, L. (2001). Developmental state perspectives. Journal article.

- Martyrs’ Survivors Benefit Proclamation No. 137/2003 (Eritrea).

- Mesfin, D. (2016). Eritrea: From self-reliance to militarized stagnation.

- OECD. (2009). Special economic zones: Performance, lessons learned and implications. https://www.oecd.org/

- Plaut, M. (2022). Eritrea’s Red Sea coast: Militarization without development. https://martinplaut.com/

- Red Sea Establishment Proclamation No. 29/1993 (Eritrea).

- Rodan, G. (2004). Transparency and authoritarian rule in Singapore. Journal article.

- Sen, A. (2015). Development as freedom. Anchor Books.

- Shawi, M. (n.d.). Singapore’s transformation from developing nation to global economic success. Medium. https://medium.com/@iamminshawi/singapores-transformation-from-developing-nation-to-global-economic-success-c19755ce72d1

- Singapore Economic Outlook. (2023–2028). Singapore economic outlook for the next five years.

- UN Commission of Inquiry on Human Rights in Eritrea. (2015). Report of the commission of inquiry on human rights in Eritrea. United Nations.

- UN Human Rights Council. (2019). National report submitted in accordance with paragraph 5 of the annex to Human Rights Council resolution 16/21: Eritrea.

- UN Monitoring Group. (2011). Report of the monitoring group on Somalia and Eritrea. United Nations.

- UN Monitoring Group. (2014). Report of the monitoring group on Somalia and Eritrea (S/2014/727). United Nations.

- UN Monitoring Group on Eritrea. (2016). Report pursuant to Security Council resolution 2317 (2016) (S/2016/920). United Nations.

- UN Monitoring Group on Somalia and Eritrea. (2012). Final report (S/2012/545). United Nations.

- UN Panel of Experts on Sudan. (2023). Final report (S/2023/111). United Nations.

- U.S. Department of State. (2025). 2025 investment climate statements: Eritrea. https://www.state.gov/reports/2025-investment-climate-statements/eritrea

- U.S. Department of the Treasury. (2021). Federal Register (Vol. 86, No. 226).

- World Bank. (2019). Singapore: Trade logistics and trade facilitation. https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/singapore

- World Bank. (n.d.). Singapore overview

. https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/singapore/overview

- Proclamation to Establish Red Sea Trading Corporation No. 29/1993

- Compensation for Martyr’s Proclamation No. 48/1994

- Martyr’s Survivors Benefit Proclamation No. 137/2003

- van Elkan, R. (1995, December 1). Singapore’s development strategy. World Bank.

- China Daily. (2010, October 15). Sino-Eritrean trade ties strengthened. https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/world/2010-10/15/content_11416039.htm

- African Arguments. (2023, November). All the president’s men: Isaias Afwerki’s close circle. https://africanarguments.org/2023/11/all-the-presidents-men-isaias-afwerkis-close-circle/

About the author

Amanuel Tadesse, International Law and Foreign Relations Expert

Disclaimer:

The content disseminated by the Institute of Foreign Affairs (IFA) – including, but not limited to, publications, public statements, events, media appearances, and digital communications – reflects the views of individual contributors and does not necessarily represent the official positions or policies of the Institute, its partners, or any affiliated governmental or non-governmental entities.

While the IFA endeavors to ensure the accuracy, integrity, and timeliness of the information presented, it makes no representations or warranties, express or implied, regarding the completeness, reliability, or suitability of such content for any purpose. The Institute expressly disclaims any liability for errors or omissions, as well as for any actions taken or decisions made based on the information provided.

The inclusion of external links, references, or third-party resources does not constitute an endorsement by the Institute. Additionally, engagement on social media platforms – including, but not limited to, likes, shares, retweets (RTs), or reposts – shall not be interpreted as an endorsement or validation of the views expressed therein.

Readers and audiences are encouraged to exercise critical judgment and seek independent verification when interpreting or relying upon any information disseminated through publications and posts on the Institute’s platforms or representatives.