Source: Analysis Africa

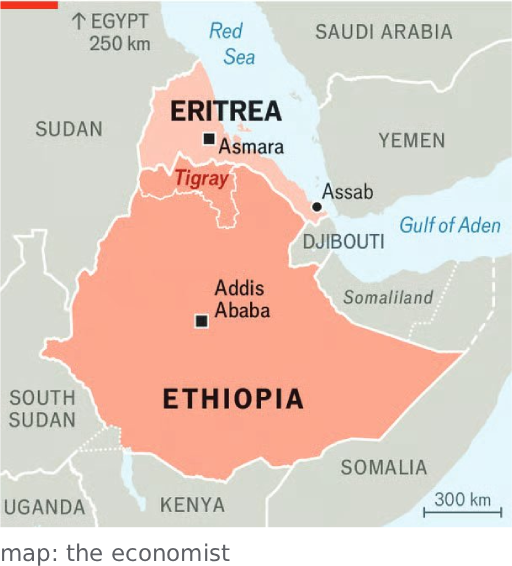

Eritrea’s sovereignty is under threat from an expansionist Ethiopia

If the past is a foreign country, its name is surely Eritrea. Residents of Asmara,

its capital, pootle around in ancient Fiat 500s, wistfully gliding past art-deco

cinemas, ornate villas and grand colonnades. These are (or were) the architectural

triumphs of long-vanquished Italian colonists, whose peeling walls seem poetical in

their decline. Equally anachronistic, if rather less endearing, is Isaias Afwerki,

Eritrea’s dictator since 1991. Soon to be 80, he still regularly denounces the

“misguided policies” of John Foster Dulles, a former American secretary of state, as

if Dwight Eisenhower were still president.

Mr Isaias has almost single-handedly turned back the clock on his country’s

development. Eritrea was once one of Africa’s most industrialised parts. Now even

the most basic goods, like soap or bottled water, have to be imported. Perhaps a

third of the population has fled abroad to escape Mr Isaias’s system of indefinite

military conscription, which the un has compared to mass enslavement, leaving

empty villages, shuttered shops and derelict farms.

Its enemies sense weakness, especially a newly irredentist Ethiopia, from which

Eritrea seceded in 1993 after a three-decade armed struggle led by Mr Isaias. Abiy

Ahmed, Ethiopia’s messianic prime minister, has openly declared that he intends to

gain control over one of Eritrea’s Red Sea ports. Many suspect his real ambition is

to overthrow Mr Isaias and perhaps even reannex Eritrea. Ethiopia has amassed a

menacing new arsenal of missiles, fighter jets and drones. “They can turn Asmara

into Gaza if they want,” says a former Western diplomat.

Can Eritrea survive? More than most places, its past is prologue. It was a late 19th-

century Italian colony, its name deriving from “Erythra Thalassa”, ancient Greek for

the Red Sea. In 1935 Benito Mussolini used it as a base for invading Ethiopia, which

his fascist forces occupied until British troops booted them out in the second world

war, restoring Haile Selassie, Ethiopia’s exiled emperor, to his throne.

But what then to do with Eritrea? One plan involved partition. The Muslim

lowlands in Eritrea’s west would be annexed to Sudan, while the central Christian

highlands would form a new state with Tigray, a region in northern Ethiopia to

whose people Eritrean highlanders are close kin. Haile Selassie, however, was

hostile to the idea of a “Greater Tigray”, which would have shrunk his empire. He

also coveted access to the Red Sea. Insisting that Eritrea belonged to Ethiopia, he

annexed it in 1962. A guerrilla insurgency ensued. Mr Isaias’s rebels won

independence in 1993.

Like Haile Selassie, Mr Abiy seems in thrall to imperial dreams of controlling the

Red Sea—and therefore Eritrea. On September 27th the Ethiopian army declared it

would “pay any sacrifice” to win back the port of Assab. In July one of Mr Abiy’s

circle called for the two countries to be joined in a “supranational union”.

Mr Abiy reckons his drones can deliver victory. Yet an invasion would be fiercely

resisted. Mr Isaias may be hated, but few Eritreans “would like to see Ethiopia

back”, says Mohamed Kheir Omer, an exiled Eritrean scholar. Eritrea would also

probably get support from Egypt and the Sudanese Armed Forces (saf), which it

has backed in Sudan’s current civil war, as well as from the Tigray People’s

Liberation Front (tplf), the party that rules Tigray.

This coalition could still deter Mr Abiy. But Eritrea’s rapprochement with Tigray, in

particular, may prove consequential in other ways, too. In a bloody border war

between 1998 and 2000, the Ethiopian army, then led by the tplf, trounced Eritrea.

Though Ethiopia refrained from advancing to Asmara to topple his government, the

humiliation left Mr Isaias and many of his countrymen with an enduring hatred for

the tplf. When Mr Abiy himself went to war against the group, between 2020 and

2022, Mr Isaias sent troops into Tigray to fight on the Ethiopian government’s side,

where they massacred civilians, raped women and looted widely.

But since then, Mr Isaias and the tplf appear to have struck up a tactical alliance

against Mr Abiy. Some influential Tigrayans want more than a temporary military

pact. “The border [between Tigray and Eritrea] was imposed on us by colonialism,”

says a senior tplf official. “I see every reason for a serious reconfiguration.”

So “Greater Tigray” is back on the agenda. The violence Mr Abiy unleashed in 2020

led many in Tigray to demand secession from Ethiopia. While most Tigrayans

despise Mr Isaias, some reckon his regime is doomed. Uniting with their Tigrinya-

speaking cousins in Eritrea would boost an independent Tigray—and give access to

the sea. Many Tigrayans have relatives in Eritrea (Mr Isaias’s own mother was of

Tigrayan descent). “If there is any logic in history, they should reunite,” says Haggai

Erlich, a prominent historian of Ethiopia and Eritrea.

Other experts consider this fanciful. “Do you think the fact that the British and the

Irish speak English,” scoffs a sceptical Tigrayan, “is enough to make them one

country?” Realistic or not, long-buried questions of history are being dug up and re-

examined. From such bloodstained soil further havoc may yet spring. ■

Sign up to the Analysing Africa, a weekly newsletter that keeps you in the loop about the

world’s youngest—and least understood—continent.